Billions of dollars have been spent on the war on poverty; in Sandtown, the Baltimore neighborhood that was damaged by the riots, twenty years ago Jim Rouse of the Rouse Company spearheaded an investment of $130,00,000 in public and private finds, so the neighborhood has hardly suffered from neglect. Baltimore is in the top tier of cities in the amount of money it spends on public education. But generations of poor people are growing up uneducated and unemployable – and it is not a question of race, because poor counties in Kentucky are as bad off or worse than city slums (although it is hard to get a riot going in the Kentucky hollows).

Psychologists and sociologists have tried to identify the root of the problem. It seems to be in the earliest upbringing of children.

The brain is most plastic in the first three years of life, and these years are therefore crucial for the future life of the child in education and employment. Researchers have discovered major differences in the way that different socio-economic classes raise their children in during the first years of life.

Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley at the University of Kansas selected a cross section of families and recorded their verbal interactions with their children.

Hart and Risley recruited 42 families to participate in the study including 13 high-income families, 10 families of middle socio-economic status, 13 of low socio-economic status, and 6 families who were on welfare. Monthly hour-long observations of each family were conducted from the time the child was seven months until age three. Gender and race were also balanced within the sample.

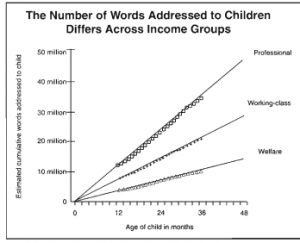

They then extrapolated what the differences amounted to in the first three years of life and published their findings in The Early Catastrophe: the Thirty Million Word Gap by Age 3 (analyzed at a Rice University site).

Children from families on welfare heard about 616 words per hour, while those from working class families heard around 1,251 words per hour, and those from professional families heard roughly 2,153 words per hour.

This means by age four a child in a middle-class family had heard 30,000,000 more words than a child from a welfare family.

What that means is that there is a gap, extremely difficult to surmount, in the educability of the child.

Within a child’s early life the caregiver is responsible for most, if not all, social simulation and consequently language and communication development. As a result, how parents interact with their children is of great consequence given it lays a critical foundation impacting the way the children process future information many years down the road. This study displays a clear correlation between the conversation styles of parents and the resulting speech of their children.

Not only does the number of word differ, the type of words differs:

What they found was that higher-income families provided their children with far more words of praise compared to children from low-income families. Children’s vocabulary differs greatly across income groups. Conversely, children from low-income families were found to endure far more instances of negative reinforcement compared to their peers from higher-income families. Children from families with professional backgrounds experienced a ratio of six encouragements for every discouragement. For children from working-class families this ratio was two encouragements to one discouragement. Finally, children from families on welfare received on average two discouragements for every encouragement.

The cumulative effect is huge:

by age four, the average child from a family on welfare will hear 125,000 more words of discouragement than encouragement. When compared to the 560,000 more words of praise as opposed to discouragement that a child from a high-income family will receive, this disparity is extraordinarily vast.

The effect of this disparity in early education is also highly significant:

To ensure that these findings had long-term implications, 29 of the 42 families were recruited for a follow-up study when the children were in third grade. Researchers found that measures of accomplishment at age three were highly indicative of performance at the ages of nine and ten on various vocabulary, language development, and reading comprehension measures. Thus, the foundation built at age three had a great bearing on their progress many years to come.

When these children have their own children, they will raise them in the way they were raised:

Even patterns of parenting were already observable among the children. When we listened to the children, we seemed to hear their parents speaking; when we watched the children play at parenting their dolls, we seemed to see the future of their own children.

Nor are differences simply psychological. Early stimulation in life has been shown to help the brains of animals develop, and the differences in the amount and type of words that children hear may at least in part explain the brain differences that have been observed between poor children and better-off children. (see here and here and here),

“We know from nonhuman animal studies that being left in cages without toys and exercise, without stimulation and opportunities to explore, can cause a decrease in the generation of neurons and synapses in the brain,”

If the mother refrains from use of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, the brains of poor children and better-off children are the same at birth. But then they start to diverge, as MRI studies have shown:

By age 4, children in families living with incomes under 200 percent of the federal poverty line have less gray matter — brain tissue critical for processing of information and execution of actions — than kids growing up in families with higher incomes.

The differences among children of the poor became apparent through analysis of hundreds of brain scans from children beginning soon after birth and repeated every few months until 4 years of age. Children in poor families lagged behind in the development of the parietal and frontal regions of the brain — deficits that help explain behavioral, learning and attention problems more common among disadvantaged children.

Poorer children have already had far less development through praise and verbal interactions. They are then put into an environment in which they do not fare well, and they have also not developed the brain centers for self-control.

The difference in brain growth increases with age:

“You start seeing the separation in brain growth between the children living in poverty and the more affluent children increase over time, which really implicates the postnatal environment.”

Children whose brains have fared to develop do not do well in school. They then become unemployable. Boys especially go down this path. They become violent, end up in prison, and are made even less employable.

90% of brain development occurs by age four. The brain is still plastic after age four, but its plasticity decreases with age, as any adult who has tried to learn a foreign language can testify.

To some extent, simple stimulation, talking, reading, can help overcome this lack of early brain development, but the older the child the harder it is to overcome the gap.

The key period in a child’s life is from conception to age four. How can children from poor backgrounds be given a brain development that will enable them to benefit from education and eventually be employed?

First of all, pregnant women have to be convinced or cajoled not to hurt their unborn child by using drugs, alcohol, or tobacco. This is not easy.

Secondly, they have to learn good parenting styles: talking to the child, praising the child, reading to the child.

What this means is that anti-poverty efforts should concentrate on the first years of life. Donna Housman, a psychologist and head of the Beginnings School in Weston, Massachusetts wrote to the New York Times:

Scientific research supports a fundamental approach that is narrowly tailored to the most critical period of life

Indeed, the case studies for early childhood education are remarkable, but most proposals target four-year-olds. Four years is too late when it comes to child development; we can start the learning process much earlier because children are born ready to learn.

How can this be accomplished? There are many obstacles.

Some parents care more about their drugs than their children. The studies by necessity focus on children who live in stable environments and can be tracked, and the verbal interaction study explicitly excluded children whose mothers used drug or had psychological problems. The studies looked at the better-off of the children of the poor, not the children of the lowest underclass.

Either children have to be taken away from the worst parents, or they have to be written off. The parents won’t change.

Many parents will see no reason to change. They were raised in a certain way, and will raise their children that way. It will be difficult to convince such parents that it is in the long-range interest of the children to raise them in a different way. Such parents may love their children, but they discipline them harshly and do not talk to them. Can such parents be persuaded to change?

Churches are the most likely agents for such a change. Parents can be offered help by church members, who can model how to interact with children in a loving, affectionate way. Obviously religions based on the Bible provide a solid basis for reading and story-telling to children.

Other parents want help, and they can be reached through such institutions as Harlem Baby College. Its site explains:

The Baby College gives expectant parents and parents of children ages 0-3 a strong understanding of child development and the skills to raise happy, healthy babies. Through workshops and home visits over the course of a 9-week term, parents gain expertise in a number of areas, including child behavior and safety; communication and intellectual stimulation; linguistic and brain development; and health and nutrition. The curriculum is also designed to promote a sense of community. Time is devoted in each class to sharing and discussing personal experiences, thus giving participants an important outlet, a crucial source of support, and an opportunity to learn from their peers.

Every city should have several of these in poor and immigrant neighborhoods.

Although a good portion of the American population dislikes anti-poverty programs, mostly because they do not seem to work or do nothing to prevent anti-social behavior like the Baltimore riots, everyone (well, almost everyone) loves babies, and would not oppose funding such programs, especially if they head off later and far more expensive problems.