Those who think that American politics suffer from unprecedented incivility and polarization do not know much about American history.

Cornelius van Wyck Lawrence (1791- 1861) was the first cousin four times removed of my wife. He married three times, Maria C. Prall, (1797-1820), Rachel Ann Hicks (1798-1838), and lastly Lydia Ann Lawrence (1811-1879) who was his cousin and my wife’s third great-grand aunt. She was the daughter of Judge Effingham Lawrence and the widow of her own cousin, Edward Newbold Lawrence, my wife’s third great-grandfather. The Lawrences developed a habit of marrying first, second, and third cousins and in one case two sisters in a row. The genealogical chart looks like the utility map of New York City. It also may have had some genetic consequences, as we shall see in the case of the Louisiana Lawrences.

But to return to Cornelius, who was born on February 28, 1791 at the ancestral Lawrence lands in Bayside, Queens County.

An enemy claimed that Cornelius was

“Of a highly respectable Quaker family on Long Island….He was a farmer’s boy, and worked many a long day in rain and sunshine on Long Island. There were few lads with twenty miles of him that could mow a wider swarth or turn a neater furrow.”

But there were richer fields to be harvested in Manhattan.

Cornelius got his start in 1812 at Shotwell, Hicks & Co, which became Hicks, Lawrence and Co., an auction and dry goods firm on Pearl Street in Manhattan. Willett Hicks was a Quaker preacher who claimed to have converted Thomas Paine on his death bed.

Willett Hicks by Rembrandt Peale

In 1824 Cornelius became director of City Bank. Cornelius retired from the auction firm in 1832 with a large fortune, which was fortunate for him because it was later ruined in the panic of 1837, and Hicks was left bankrupt. Cornelius married Hick’s daughter, Rachel.

Cornelius served as a congressman from 1832-1834. Like other businessmen he approved of the Bank of the United States, and was in fact a director, while the president of the New York branch of the Bank of the United States was Isaac Lawrence (his distant cousin). But Cornelius was a Jacksonian Democrat, and they opposed the Bank.

Therefore against his convictions Cornelius opposed the Bank of the United States. His enemies seized upon this. Citing his own letters, they said

His judgment was avowedly on one side and his votes on the other. The prospect of adding to his wealth by the sacrifice of his opinions were in one scale – honor and honesty were in the other – in private …he admitted the removal (of the public treasury) was inexpedient.

They continued:

Yet he voted for the removal on a pledge, well kept, that he would get the fingering of two millions of dollars of these deposites himself, for a bank to be started in Wall street, with special privileges, and called the Bank of the State of New York, of which he and his cronies should have the control, the jugglery of disposing of its shares, etc.

When Cornelius visited New York and his merchant friends asked for an explanation of is actions, he explained that

he had bound himself BY A WRITTEN PLEDGE to uphold the party. Such was his sense of the embarrassments of his situation that HE ACTUALLY WEPT.

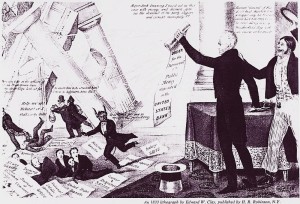

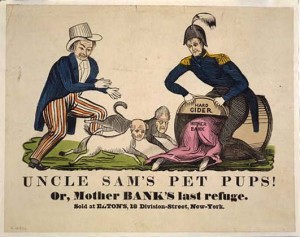

President Andrew Jackson in 1833 refused to renew the charter of the second Bank of the United States, the devil’s bank, as the Jacksonians called it.

The funds of the United States were withdrawn and deposited in special state banks, called pet banks.

Prior to 1834 mayors of the City of New York had been appointed, first by the colonial government, and then by the Common Council, the predecessor of the City Council. In the spirit of democracy, it was decided to let the voters of New York elect the sixty-first mayor.

Cornelius Lawrence ran as a Tammany Democrat against Gulian Crommelin Verplanck, the Whig candidate, a poet and former Democrat.

A Man with the Soul of a Poet

His enemies described Cornelius’s decision to run in these terms:

the crying congressman, the weeping stock-jobber could have resigned had he disliked the party drill — but it brought him plunder, and he blubbered and held on, and afterwards he lent his name as a candidate for the mayoralty to uphold the gamblers he voted with in public…”

The mayoral election of 1834 was everything the nativists feared. They had warned

This country never committed a more fatal mistake than in making its naturalization laws so that the immense immigration from foreign countries could, after a brief sojourn, exercise the right of suffrage.

To ask men, the greater part of whom could neither read nor write, who were ignorant of the first principles of true civil liberty, who could be bought and sold like sheep in the shambles, to assist us in founding a model republic, was a folly without a parallel in the history of the world, and one of which we have not yet begun to pay the full penalty.

There was no registry of voters, there was only one polling place per ward, and the voting extended over three days. It was a recipe for disaster.

An observer described the democratic electoral process:

On the occasion we speak of a gang of Jackson shoulder-hitters, headed by an ex Alderman, and armed with clubs, sling-shots, and knives, broke into the committee-room of the opposing faction and nearly killed some 15 or 20 of them. Then they tore down the banners, destroyed the ballots, and made a wreck of everything. The Whigs asked the Mayor for help, but he would not furnish it, alleging that all his forces were engaged. The Whigs were left to protect themselves and they did it. In these times elections lasted three days. The second morning Masonic Hall was packed with Whigs who meant to crush the mob. They had a battalion 1,800 strong ready to march at a moment’s notice.

This had the effect of keeping the peace and keeping free access to the polls. But the roughs were all the time firing up with drink, and on the third day were ready for anything. Early in the forenoon they tried to capture from a Whig procession the little miniature frigate Constitution. This led to a fierce conflict in front of Masonic Hall. The hall was assaulted, and the Mayor, Sheriff, and 40 Watchmen, were finally driven off. The Mayor [Gideon Lee] was wounded, and Police Capt. Flagg was killed. The rioters rushed into the hall, and the Whigs were forced to fly through the windows. The Mayor declared the City in insurrection, and called for help from the Navy-yard and Fort Columbus, but the Federal officers could not interfere. Finally, Gen. Sandford called out the military.

Even with the military, which was largely pro-Jackson, on his side. Lawrence won by only 181 votes.

Cornelius was mayor, and had an immediate crisis on his hands.

The Anti-abolitionist riots of 1834, the Farren Riots, occurred in over a series of four nights, beginning on July 7, 1834. Their origins lay in the combination of nativism and abolitionism among the Protestants who had controlled the city since the Revolution, and the fear and resentment of blacks among the growing underclass of Irish immigrants.

The urban rumor mill was busy manufacturing stories:

In May and June 1834, the silk merchants and ardent Abolitionists Arthur Tappan and his brother Lewis stepped up their agitation for the abolition of slavery by underwriting the formation in New York of a Female Anti-Slavery Society. Arthur Tappan drew particular attention by sitting in his pew with Samuel Cornish, a mixed-race clergyman of his acquaintance. By June, lurid rumors were being circulated by the champion of repatriating “colonization,” James Watson Webb, through his newspaper Courier and Enquirer: abolitionists had told their daughters to marry blacks, black dandies in search of white wives were promenading Broadway on horseback, and Arthur Tappan had divorced his wife and married a black woman.

So the Irish, resenting competition from free blacks, rioted.

Irishmen about to engage in Inter-racial Dialogue

On Wednesday evening, July 9, three interconnected riots erupted. Several thousand whites gathered at the Chatham Street Chapel; their object was to break up a planned anti-slavery meeting. When the abolitionists, alerted, did not appear, the crowd broke in and held a counter-meeting, mocking the ‘black style’ of preaching and calling for deportation of blacks to Africa.

The mob targeted homes, businesses, churches, and other buildings associated with the abolitionists and African Americans. More than seven churches and a dozen houses were damaged, many of them belonging to African Americans. The home of Reverend Peter Willaims, an African-American Episcopal priest, was damaged, and his St. Philip’s African Episcopal Church was utterly demolished. One group of rioters reportedly carried a hogshead of black ink with which to dunk white abolitionists. In addition to other targeted churches, the Charlton Street home of Rev. Samuel Hanson Cox was invaded and vandalized. The rioting was heaviest in the Five Points.

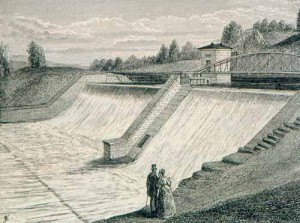

Cornelius also faced a quieter but in the long term more deadly problem. New York, with a population of 200,000, relied upon wells, which were increasingly unsanitary and inadequate for fire protection. There had been cholera epidemics in 1832 and 1834, Voters in all but the poorest districts voted overwhelmingly for a massive water project. Construction had not even begun when its necessity was demonstrated by the Great Fire of 1835.

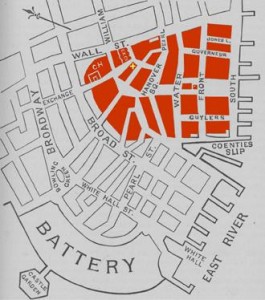

A most awful conflagration occurred at New York on the 15th of December, by which 600 buildings were destroyed, comprising the most valuable district of the city, including the entire destruction of the Exchange, the Post Office, and an immense number of stores. The fire raged incessantly for upwards of fifteen hours. The shipping along the line of wharfs suffered greatly; several vessels were totally destroyed. The property consumed is estimated at 20,000,000 dollars. (Perhaps $500,000,000 2015 dollars.)

Many insurance companies were ruined by the fire and insurance companies began the exodus to Hartford, Connecticut.

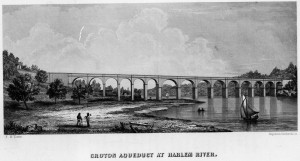

Cornelius began the construction of the Croton Reservoir and aqueduct.

Cornelius won the election of 1836, running against, among others, Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph, nativist, and anti-clerical. That year Cornelius supervised the creation of the Bank of the State of New York (one of the pet banks) in which Van Buren deposited $2,000,000 (perhaps $50,000,000 in 2015 dollars). He held the presidency from 1836 to 1845, when he became Collector of the Port of New York. He then turned over the presidency of the bank to his brother Joseph, who held it until 1849, when Cornelius took it over again until he retired in 1857.

Cornelius lost the election of 1837 because of the Panic, a panic created (some historians insist) by the termination of the Bank of the United States and consequent destabilization of the financial system. However, Cornelius did not suffer overly.

For twenty years he held the office of President of the Bank of the State of New-York. He was Director of the Branch Bank of the United States, of the Bank of America, a trustee of the New-York Life and Trust Company, and a director of the Howard Insurance Company, the City Fire Insurance Company, the Fireman’s Insurance Company, etc.

The Elderly Cornelius

Life was not all work and no play for Cornelius. A older history of New York has the tantalizing outlines of a story: Cornelius

“had the ice cream and strawberries of everything in life – in commerce, in politics, in wives, in finances and in religion…. He had a peculiar way of carrying his spectacles behind his back while he looked at all the pretty girls he met.

“One of them led him a sad dance. Mr. Lawrence, the most respected man in the city, was led into an ambuscade and made the victim of a plot. It was a sad business, lost the old gentleman a great deal of money, and caused him any quantity of mental misery.”

What had happened is that Cornelius, like almost every other male in New York over the age of 14, had participated in the Sporting Life. This was a libertine male culture, revolving around sports and prostitutes. Cornelius paid blackmailers $100,000 (about $3,000,000 in 2015 dollars, and was what one reference work estimated as his net worth) to keep his past quiet, so his indiscretions must have been truly spectacular.

The Sacramento Daily Union of November 18, 1856 reported:

The Heavy Black Mail Operations. — Some months ago, as will be remembered, Ex-Mayor Cornelius W. Lawrence preferred a charge of perjury against Mr. A. Brown, formerly a Deputy U. S. Marshal of this city, for swearing falsely in one of the Law Courts. It was expected that, during the examination into the merits of this charge of perjury, certain facts relating to enormous black mail operations, which Brown practiced upon the Ex-Mayor, at intervals during a period of eighteen years, by which he obtained from Mr. Lawrence over $100,000, would bo brought to the notice of the Court, but owing to the continued absence from Court of Mr. Lawrence on every occasion, when the case was to have been examined, the magistrate, Justice Flandreau, was determined to dismiss the complaint, and did so. Brown, it will be remembered, was stated to have been in possession of certain secrets touching the Ex-Mayor’s intimacy with a female twenty years or longer ago, and by means of threats to expose, he succeeded in getting from Mr. L. large sums of money at various times, in the aggregate amounting to over $100,000. .For years tho Ex-Mayor suffered the infamous extortion to go on, but finally he refused giving Brown any more money and then only the circumstances of Mr. L.’s youthful indiscretion was made public, although some of his friends knew of it years ago, and advised him not to give Brown a cent, but to let him make the expose and then have the affair cleared up. Mr. Lawrence, however, declined this course, and has, accordingly, suffered from Brown’s extortions. The latter was under bonds of $5,000 to answer the charge of perjury, but is now discharged and his bondsmen liberated. He was formerly owner of a public house called ” the Red House,” at Harlem, and for years past has lived extravagantly. —

The Red House tavern in Harlem was a mecca of the fast set’s “manly sports,” sports which were not limited to cricket and horse racing.

In honor of his service as Collector of the Port of New York, the revenue cutter Cornelius W. Lawrence was named after him. It had a brief and checkered history. It was a Baltimore clipper (i.e., fast), built in Foggy Bottom, and commissioned October 1848.

She was assigned to the west coast, with Captain Fraser’s orders being to secure the revenue, enforce U.S. laws on the seas, aid distressed vessels, and to sound and chart the new territory’s harbors and inlets. With a crew of 43 aboard, with most of Fraser’s officers being political appointees with no seagoing experience, Lawrence set sail for the Pacific on 1 November 1848 around Cape Horn. After an arduous voyage of over 11 months, including five weeks spent attempting to sail around the Horn, she arrived in San Francisco on 31 October 1849.

Difficulties soon visited the cutter though when the crew learned of the vast fortunes being made by those hunting gold inland and Fraser soon found himself without a crew. Even his officers resigned to join the gold rush.

Eventually the Lawrence sailed again, and went to San Diego, the Hawaiian Islands, and back to San Francisco to help put down mutinies. She ran aground and was lost at the entrance to San Francisco Bay on the night of 25 November 1851. All hands were saved.

But in 1982 she was (largely) duplicated and given the name the Californian, becoming the state’s own tall ship.

After his death Cornelius had a fireboat named after him, presumably in honor of his work in the Volunteer Fire Department and in bringing water to New York City to prevent fires. It had a longer career.

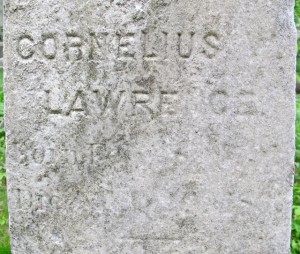

Cornelius died on February 20, 1861 and was interred in the Lawrence family plot in Bayside.

Sic transit gloria Novi Eboraci.

My Gradfather was James Alexander Lawrence born in 1883 possibly in Paterson, N.J. He told us that he was the first male in the family not named Cornelius and that his Great Grandfather was Mayor of New York City. Wondering if this is the same person. Please advise. Thanks.

“Gradfather”? wtf