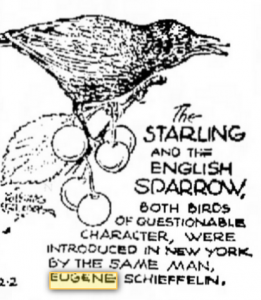

All throughout North America, one has only to look to the skies to see, all too often, a living memorial to the work of Eugene Schieffelin (1827-1906). Eugene was the grandson of Jacob Schieffelin and Hannah Lawrence, and therefore my wife’s second cousin, four times removed.

Kim Todd meditates upon Eugene:

I imagine him a quiet, unassuming man. While his relatives were making headlines all through the 1800s – stewing in jail on charges of bigamy, leading expeditions to the West, being captured by Crow Indians and being released moments before death, amassing large fortunes in business and giving interviews to the New York Times about the servant problem – Eugene Schieffelin was working for the family drug manufacturing company, attending meetings of the New York Zoological Society, and reading Shakespeare.

This combination lead Eugene down dangerous paths; he joined the American Acclimatization Society and became its chairman.

As part of globalization in the nineteenth centrum, Europeans transferred animals and plants from continent to continent, often for economic reasons. The Caribbean islands were the recipient of tropical plants from all over the British and French empires. In 1854, the Société zoologique d’acclimatation was founded in Paris and urged the goverment too introduce foreign animals both to provide meat and to control pests. The group inspired the formation of similar societies around the world, including the United States. In 1877 the American Acclimatization Society was founded.

It is said (although some sceptics deny it) that Eugene was a devotee of Shakespeare, and wanted to introduce every bird species mentioned in the Bard’s works.

William Cullen Bryant admired the Schieffelins and wrote his poem The Olde-World Sparrow after spending an evening with the William Henry Schieffelin, who had just released a shipment of sparrows into his yard, but some suspect it was Eugene who did it or at least inspired it.

We hear the note of a stranger bird

That ne’er till now in our land was heard.

A winged settler has taken his place

With Teutons and men of Celtic race;

He has followed their path to our hemisphere

The Old-World Sparrow at last is here.

He meets not here, as beyond the main,

The fowler’s snare and poisoned grain,

But snug-built homes on the friendly tree;

And crumbs for his chirping family

Are strewn when the winter fields are drear,

For the Old-World Sparrow is welcome here.

The insects legions that sting our fruit

And strip the leaves from the growing shoot,

A swarming, skulking, ravenous tribe,

Which Harris and Flint so well describe

But cannot destroy, may quail with fear,

For the Old-World Sparrow, their bane, is here.

The apricot, in the summer ray,

May ripen now on the loaded spray,

And the nectarine, by the garden-walk,

Keep firm its hold on the parent stalk,

And the plum its fragrant fruitage rear,

For the Old-World Sparrow, their friend is here.

That pest of gardens, the little Turk

Who signs, with the crescent, his wicked work,

And causes the half-grown fruit to fall,

Shall be seized and swallowed, in spite of all

His sly devices of cunning and fear,

For the Old-World Sparrow, his foe, is here.

And the army-worm and the Hessian fly

And the dreaded canker-worm shall die,

And the thrip and slug and fruit-moth seek,

In vain, to escape that busy beak,

And fairer harvests shall crown the year,

For the Old-World Sparrow at last is here.

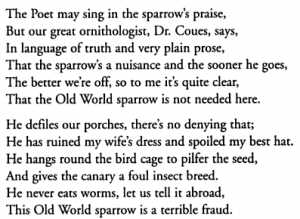

Very quickly sparrows wore out their welcome. In 1881 Fred Mather versified:

The starling is mentioned in Henry IV, Part 1 when Hotspur considers using its vocal talents to drive the King mad. Since King Henry was refusing to pay a ransom to release his disloyal brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer, Hotspur says: “I’ll have a starling shall be taught to speak nothing but “Mortimer,” and give it him, to keep his anger still in motion.” Eugene did not notice that Hotspur regards the starling as a pest.

Schieffelin released starlings twice. The first time didn’t take so he did it again. On March 6, 1890 he released 80 European starlings in Central Park. They took. By 1928 they were found as far west as the Mississippi. By 1942 they were in California.

By the mid-1950’s they numbered more than 50 million. They are now over 200 million, often in flocks of over a million, called a murmuration.

Farmers are unhappy with starlings.

Roosting in hordes of up to a million, starlings can devour vast stores of seed and fruit, offsetting whatever benefit they confer by eating insects. In a single day, a cloud of omnivorous starlings can gobble up 20 tons of potatoes.

What they don’t eat they defile with droppings. They are linked to numerous diseases, including histoplasmosis, a fungal lung ailment that afflicts agricultural workers; toxoplasmosis, especially dangerous to pregnant women, and Newcastle disease, which kills poultry.

Farmers have tried

Helium balloons

Roman candles

Rockets

Whirling shiny objects

Noisemakers shot from fifteen-millimeter flare pistols

Firecrackers blasted from twelve gauge shotguns

Explosions of propane gas

Artificial owls

Airplanes

Distress calls broadcast on mobile sound equipment

Chemical’s derived from peppers

Chemicals that cause erratic behavior

Chemicals that cause kidney failure

Chemicals that wet feathers in the winter and keep them wet until the birds freeze to death

Nothing works. People keep trying

Few creatures have inspired so much folly. In 1948 the superintendent of sanitation in Washington, D.C., having failed to rout the birds with balloons and artificial owls, tried exposing them to itching powder. The police used mechanical hawks. An Interior Department consultant proposed placing grease around starling feeding sites, hoping they would track the gook back to their nests and cover their own eggs, preventing them from hatching.

Later, electricians laid live wires across the Corinthian columns of the Capitol and other prominent buildings to discourage starlings from roosting. They simply took up residence in whatever nearby structures were not hot-wired. When the White House grounds were plagued, speakers were set up to broadcast recordings of starlings rasping out their alarm call. (The birds vacated to sycamore trees on Pennsylvania Avenue, whose branches were then smeared with chemicals to irritate their feet.) Later, the war against starlings turned nasty. In the early 1960’s a Federal Government experiment with poisoned pellets killed thousands of starlings in Nevada. From 1964 to 1967 nine million starlings were poisoned in California’s Solano County in an effort to protect feed lots. During that same period the California Department of Agriculture experimented with irradiating captive starlings with lethal doses of cobalt-60. In Providence, R.I., officials set off Roman candles near flocks.

The most innovative solution, though, was advanced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1931. ”When the breasts of these birds have been soaked in a soda-salt solution for 12 hours and then parboiled in water, which is afterwards discarded, they may be used in a meat pie that compares fairly well with one made of blackbirds or English sparrows.” But, cautioned the author, the gamy taste was not for everyone.

Starling pot pie

Starlings are terrorists:

In 1960 a Lockheed Electra plummeted seconds after taking off from Logan Airport in Boston, killing 62 people. Some 10,000 starlings had flown straight into the plane, crippling its engines. Any bird in the wrong place can pose such a danger, but it is the ever-present starling that pilots fret over the most.

Nor is the damage that starlings caused confined to commercial crops, health, and airplanes. Starlings are vicious little buggers and drive out native species.

If starlings have a noteworthy genetically programmed personality characteristic, it is aggression. They wait until other birds have created cavities for nests, then harass the architects until the abandon the site. Sometimes a starling enters a hoe while the owner is gone. When the bird returns, the starling leaps onto its back, clinging and pecking it all the way to the ground. Even when it has claimed a nesting cavity, a starling may continue to abuse other birds breeding nearby, plucking their eggs out of the nest and dropping them in the dirt. One ornithologist watched a starling dangle a piece of food in front of the nesting cavity of a downy woodpecker. When the young woodpecker reached out of the hole for the bait, the starling dispatched it with a quick jab of the beak.

My wife witnessed such an incident. Two flickers had built their nest in the hollow of an old maple tree at Waterhole Cove. Starlings moved in and evicted the flickers. What the starlings did not know is that the tree had another resident. My wife saw the starlings bolt of the tree, screaming. Their incessant chatter had awoken the snake that had been peacefully sleeping in the base of the tree, and he was investigating upstairs to see what was causing the racket.

Eugene is seen by modern biologists as “an eccentric at best, a lunatic at worst.” The society’s effort to introduce Shakespeare’s birds into New York’s public parks was described as “infamous” by the ecologist John Marzluff, who also called the establishment of a breeding population of starlings the society’s “most notorious introduction.” By 1898 the Federal government took alarm, and by 1900 the Lacey Act tried to control the importation of dangerous species. Ah, the classic barn door.

Eugene died of paralysis at his home in Newport, August 15, 1906. He married Catherine Tonnele Hall in 1858 but had no descendants. His works live after him.

“What hast thou done?” Titus Andronicus 4.2.

For a further meditation, read Charles Mitchell’s The Bard’s Bird.