Mount Calvary Church

Baltimore

A Roman Catholic Parish

Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

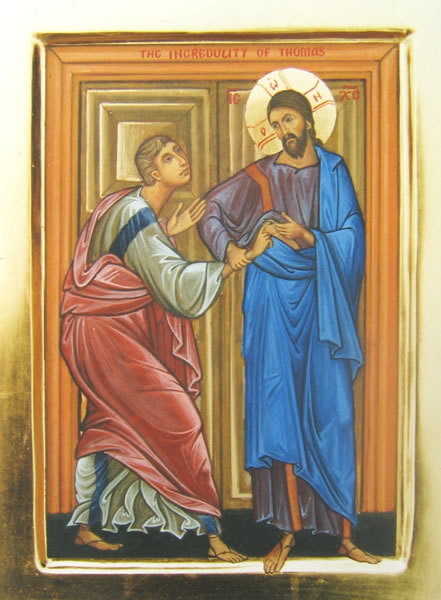

Thomas Sunday

Dominica in albis

Divine Mercy Sunday

April 8, 2018

Hymns

O sons and daughters, let us sing (O FILII ET FILIAE)

That Easter day with joy was bright (PUER NOBIS)

How oft, O Lord, Thy face hath shone (DUKE STREET)

Anthems

Quia vidisti me, Luca Marenzio (1556-1599)

Quia vidisti me, Palestrina (1525-1594)

Common

Missa de S. Maria Magdelena, Healy Willan

_____________________________

HYMNS

O sons and daughters is a translation by John Mason Neale (1818-1866) of the hymn O filii et filiae, attributed to the Franciscan Jean Tisserand (died 1494). The hymn appeared in an untitled book, published in France between 1518 and 1536, with the heading ‘L’aleluya du jour des Pasques’. It was used to salute the Blessed Sacrament on the evening of Easter Day. It recounts the appearance of the Risen Christ to both the women on Easter and to the disciples in the upper room. We are addressed in the stanza How blest are they who have not seen / And yet whose faith has constant been, / For they eternal life shall win. Although we have not seen the Risen Lord with our bodily eyes, we see Him with the eyes of faith, especially in the Eucharist, and are loyal to Him.

O sons and daughters, let us sing!

The King of heaven, the glorious King,

O’er death today rose triumphing.

That Easter morn, at break of day,

The faithful women went their way

To seek the tomb where Jesus lay.An angel clad in white they see,

Who sat, and spake unto the three,

“Your Lord doth go to Galilee.”That night the apostles met in fear;

Amidst them came their Lord most dear,

And said, “My peace be on all here.”When Thomas first the tidings heard,

How they had seen the risen Lord,

He doubted the disciples’ word.“My pierced hands, O Thomas, see;

My hands, my feet, I show to thee;

Not faithless, but believing be.”No longer Thomas then denied,

He saw the feet, the hands, the side;

“Thou art my Lord and God,” he cried.How blest are they who have not seen,

And yet whose faith has constant been,

For they eternal life shall win.On this most holy day of days,

To God your hearts and voices raise,

In laud, and jubilee, and praise. Alleluia!

Here is the choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

The Latin original with stanzas added to it as various times:

1. O filii et filiae,

Rex caelestis, Rex gloriae,

morte surrexit hodie, alleluia.2. Et mane prima sabbati,

ad ostium monumenti

accesserunt discipuli, alleluia.3. Et Maria Magdalene,

et Jacobi, et Salome,

venerunt corpus ungere, alleluia.4. In albis sedens Angelus,

praedixit mulieribus:

in Galilaea est Dominus, alleluia.5. Et Joannes Apostolus

cucurrit Petro citius,

monumento venit prius, alleluia.6. Discipulis adstantibus,

in medio stetit Christus,

dicens: Pax vobis omnibus, alleluia.7. Ut intellexit Didymus,

quia surrexerat Jesus,

remansit fere dubius, alleluia.8. Vide, Thoma, vide latus,

vide pedes, vide manus,

noli esse incredulus, alleluia.9. Quando Thomas Christi latus,

pedes vidit atque manus,

Dixit: Tu es Deus meus, alleluia.10. Beati qui non viderunt,

Et firmiter crediderunt,

vitam aeternam habebunt, alleluia.11. In hoc festo sanctissimo

sit laus et jubilatio,

benedicamus Domino, alleluia.12.Ex quibus nos humillimas

devotas atque debitas

Deo dicamus gratias.

Here the Latin is sung by the Daughters of Mary.

The tune is hauntingly beautiful, but it is not considered a true Gregorian chant. However, the Benedictine monks of Solesme included it in the Liber Usualis.

____________________

That Easter day with joy was bright is a translation also by John Mason Neale of the Latin hymn Aurora lucis rutilat, probably by St. Ambrose (330-397). Augustine said that Ambrose set popular hymns to the meter of Roman marching songs to propagate orthodox Catholic theology, because the Arians were using hymns to propagate error. Although hymns are poems, their theological content is important, a point overlooked in some modern hymns.

That Easter day with joy was bright,

The sun shone out with fairer ray,

When, to their longing eyes restored,

The apostles saw their risen Lord.His risen flesh with radiance glowed;

His wounded hands and feet he showed:

Those scars their solemn witness gave

That Christ was risen from the grave.O Jesus, King of gentleness,

Do thou thyself our hearts possess;

That we may give thee all our days

The willing tribute of our praise.O Lord of all, with us abide,

In this our joyful Eastertide,

From every weapon death can wield

Thine own redeemed forever shield.All praise, O risen Lord, we give

To thee, who, dead, again dost live;

To God the Father equal praise,

And God the Holy Ghost, we raise.

Here is the Mormon Tabernacle Choir; this performance emphasizes the folk, dance-like origin of the tune. Here is the version from the 1982 Hymnal at St. Bartholomew’s. Here is a version for brass and organ. It seems to be favored by hand bell ringers. And here is a jazz version.

The Latin hymn is attributed to St. Ambrose, but hymns modeled after his were classified as Ambrosiani. Here is the Gregorian melody using a slightly different text. Note the lovely melismas at the end of the second line of each stanza.

| AURORA lucis rutilat, caelum laudibus intonat, mundus exultans iubilat, gemens infernus ululat, |

LIGHT’S glittering morn bedecks the sky, heaven thunders forth its victor cry, the glad earth shouts its triumph high, and groaning hell makes wild reply: |

| Cum rex ille fortissimus, mortis confractis viribus, pede conculcans tartara solvit catena miseros ! |

While he, the King of glorious might, treads down death’s strength in death’s despite, and trampling hell by victor’s right, brings forth his sleeping Saints to light. |

| Ille, qui clausus lapide custoditur sub milite, triumphans pompa nobile victor surgit de funere. |

Fast barred beneath the stone of late in watch and ward where soldiers wait, now shining in triumphant state, He rises Victor from death’s gate. |

| Solutis iam gemitibus et inferni doloribus, <<Quia surrexit Dominus!>> resplendens clamat angelus. |

Hell’s pains are loosed, and tears are fled; captivity is captive led; the Angel, crowned with light, hath said, ‘The Lord is risen from the dead.’ |

| TRISTES erant apostoli de nece sui Domini, quem poena mortis crudeli servi damnarant impii. |

THE APOSTLES‘ hearts were full of pain for their dear Lord so lately slain: that Lord his servants’ wicked train with bitter scorn had dared arraign. |

| Sermone blando angelus praedixit mulieribus, <<In Galilaea Dominus videndus est quantocius>> |

With gentle voice the Angel gave the women tidings at the grave; ‘Forthwith your Master shall ye see: He goes before to Galilee.’ |

| Illae dum pergunt concite apostolis hoc dicere, videntes eum vivere osculant pedes Domini. |

And while with fear and joy they pressed to tell these tidings to the rest, their Lord, their living Lord, they meet, and see his form, and kiss his feet. |

| Quo agnito discipuli in Galilaeam propere pergunt videre faciem desideratam Domini. |

The Eleven, when they hear, with speed to Galilee forthwith proceed: that there they may behold once more the Lord’s dear face, as oft before. |

| CLARO PASCHALI gaudio sol mundo nitet radio, cum Christum iam apostoli visu cernunt corporeo. |

IN THIS our bright and Paschal day the sun shines out with purer ray, when Christ, to earthly sight made plain, the glad Apostles see again. |

| Ostensa sibi vulnera in Christi carne fulgida, resurrexisse Dominum voce fatentur publica. |

The wounds, the riven wounds he shows in that his flesh with light that glows, in loud accord both far and nigh ihe Lord’s arising testify. |

| Rex Christe clementissime, tu corda nostra posside, ut tibi laudes debitas reddamus omni tempore! |

O Christ, the King who lovest to bless, do thou our hearts and souls possess; to thee our praise that we may pay, to whom our laud is due for aye. |

The tune PUER NOBIS is a melody from a fifteenth-century manuscript from Trier. However, the tune probably dates from an earlier time and may even have folk roots. PUER NOBIS was altered in Spangenberg’s Christliches Gesangbuchlein (1568), in Petri’s famous Piae Cantiones (1582), and again in Praetorius’s Musae Sioniae (Part VI, 1609).

How oft, O Lord, Thy face hath shone was written by William Bright (1824-1901) for the feast of St. Thomas on December 21. It is of course appropriate for Thomas Sunday, the Sunday after Easter, when the gospel of Christ’s appearance to Thomas is always read. Bright’s compassion for St Thomas is shown throughout this hymn, which re-tells the familiar story to bring out its full implications. The quotation in stanza 2, for example, is an example of the saint’s courage (from John 11: 16).

Here are the current words:

1. How oft, O Lord, thy face hath shone

on doubting souls whose wills were true!

Thou Christ of Peter and of John,

thou art the Christ of Thomas too.2. He loved thee well, and calmly said,

“Come, let us go, and die with him”;

yet when thine Easter-news was spread,

mid all its light his eyes were dim.3. His brethren’s word he would not take,

but craved to touch those hands of thine:

when thou didst thine appearance make,

he saw, and hailed his Lord Divine.4. He saw thee risen; at once he rose

to full belief’s unclouded height;

and still through his confession flows

to Christian souls thy life and light.5. O Savior, make thy presence known

to all who doubt thy Word and thee;

and teach us in that Word alone

to find the truth that sets us free.

Here is the tune DUKE STREET that we will be using.

They are altered slightly form Bright’s words:

How oft, O Lord, Thy Face hath shone

On doubting souls whose wills were true;

Thou Christ of Cephas and of John,

Thou art the Christ of Thomas too.He loved Thee well, and calmly said,

‘Come, let us go, and die with Him’;

Yet when Thine Easter news was spread,

’Mid all its light his eyes were dim.His brethren’s words he would not take,

But craved to touch those hands of Thine:

The bruisèd reed he did not break,

He saw, and hailed his Lord Divine.He saw Thee ris’n; at once he rose,

To full belief’s unclouded height;

And still through his confession flows

To Christian souls Thy Life and Light.O Saviour, make Thy presence known

To all who doubt Thy word and Thee;

And teach them in that word alone

To find the truth that sets them free.And we who know how true Thou art,

And Thee as God and Lord adore,

Give us, we pray, a loyal heart

To trust and love Thee more and more.

William Bright (1824- 1901) was educated at Rugby School and University College, Oxford (BA, 1846, MA, 1849). He was elected to a Fellowship of the College in 1847, and took Holy Orders (deacon 1848, priest 1850). He became a theological tutor at Trinity College, Glenalmond, Scotland, in 1851, and was appointed Bell Lecturer in Ecclesiastical History by the Scottish bishops. In 1858 he had a serious disagreement with the Bishop of Glasgow over the historical interpretation of an episode in the Reformation concerning church settlement. He was removed from office and so returned to Oxford, where he taught church history. He was appointed Professor of Ecclesiastical History and Canon of Christ Church in 1868. Among his historical publications were A History of the Church, A.D. 313-451 (Oxford, 1860), Chapters of Early English Church History (Oxford, 1878), and The Roman See in the Early Church (1896). He published sermons (The Incarnation as a Motive Power, 1889) and poems (Athanasius and other Poems, 1858, Iona and other Verses, 1886). His Hymns and Other Poems appeared in 1866, with an enlarged Second Edition in 1874.

DUKE STREET seems to have been written by John Hatton (?-1793). Little is known of his life. He may have been born at Warrington: he was known at St Helens, where he later lived, as ‘John of Warrington’. His address in St Helens was Duke Street.

He is believed to have been the composer of the tune DUKE STREET. Its first recorded appearance is in A Select Collection of Psalm & Hymn Tunes (Glasgow and Edinburgh, 1793), compiled by ‘the late Henry Boyd’.

Millar Patrick wrote of DUKE STREET: ‘What vigour you have in it! — what magnificent movement, what superb curves, every line soaring, subsiding, like the flight of a bird!’

______________________________

Anthems

Quia vidisti me, Luca Marenzio (1556-1599)

Quia vidisti me, Thoma, credidisti: beati qui non viderunt, et crediderunt. Alleluia.

Because thou hast seen me, Thomas, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed. Alleluia.

Here is the Progetto Musica.

This motet, written for the Feast of St. Thomas (but also appropriate for the Octave of Easter), is found in the composer’s collection Motectorum pro festis totius anni (first edition printed at Rome by A. Gardano in 1585, second edition printed at Venice by A. Vincenti in 1588).

Italian composer and singer Luca Marenzio (ca. 1553-1599) was considered by many Renaissance musicians to be the chief archetype of the expressive 16th-century Italian madrigal style. The text of this motet is from John 20: 29 – the Antiphon for the Feast of St Thomas, the great doubter. Marenzio’s madrigalian style of text painting is well served here. Note the homophonic emphasis given to the text “beati qui non viderunt” (blessed are they that have not seen). The motet concludes with an imitative and joyful “Alleluia.”

_______________________________

Regina coeli, Palestrina (1525-1594)

Regina caeli laetare, Alleluia. Quia quem meruisti portare, Alleluia. Resurrexit sicut dixit, Alleluia. Ora pro nobis Deum. Alleluia.

Queen of Heaven, rejoice, alleluia. For He whom you were worthy to bear, alleluia, has risen, as He said, alleluia. Pray for us to God, alleluia.

Here are the King’s Singers.

_____________________________

A Note on Nomenclature

This Sunday has several names, including Low Sunday. From the Catholic Encyclopedia:

The origin of the name is uncertain, but it is apparently intended to indicate the contrast between it and the great Easter festival immediately preceding, and also, perhaps, to signify that, being the Octave Day of Easter, it was considered part of that feast, though in a lower degree.

Its liturgical name is Dominica in albis depositis, derived from the fact that on it the neophytes, who had been baptized on Easter Eve, then for the first time laid aside their white baptismal robes. St. Augustine mentions this custom in a sermon for the day, and it is also alluded to in the Eastertide Vesper hymn, “Ad regias Agni dapes” (or, in its older form, “Ad cœnam Agni providi”), written by an ancient imitator of St. Ambrose. Low Sunday is also called by some liturgical writers Pascha clausum, signifying the close of the Easter Octave, and Quasimodo Sunday, from the Introit at Mass — “Quasi modo geniti infantes, rationabile, sine dolo lac concupiscite”, — which words are used by the Church with special reference to the newly baptized neophytes, as well as in general allusion to man’s renovation through the Resurrection. The latter name is still common in parts of France and Germany.

The name of this Feast is the origin of the name of the hunchback, Quasimodo, in Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Poor Quasimodo was a foundling who was discovered at the cathedral on Low Sunday and so was named for the Feast. He is introduced in Hugo’s book like this:

Sixteen years previous to the epoch when this story takes place, one fine morning, on Quasimodo Sunday, a living creature had been deposited, after Mass, in the church of Notre- Dame, on the wooden bed securely fixed in the vestibule on the left, opposite that great image of Saint Christopher, which the figure of Messire Antoine des Essarts, chevalier, carved in stone, had been gazing at on his knees since 1413, when they took it into their heads to overthrow the saint and the faithful follower. Upon this bed of wood it was customary to expose foundlings for public charity. Whoever cared to take them did so. In front of the wooden bed was a copper basin for alms.

The sort of living being which lay upon that plank on the morning of Quasimodo, in the year of the Lord, 1467, appeared to excite to a high degree, the curiosity of the numerous group which had congregated about the wooden bed. The group was formed for the most part of the fair sex. Hardly any one was there except old women.

In the first row, and among those who were most bent over the bed, four were noticeable, who, from their gray cagoule, a sort of cassock, were recognizable as attached to some devout sisterhood. I do not see why history has not transmitted to posterity the names of these four discreet and venerable damsels. They were Agnes la Herme, Jehanne de la Tarme, Henriette la Gaultière, Gauchère la Violette, all four widows, all four dames of the Chapel Etienne Haudry, who had quitted their house with the permission of their mistress, and in conformity with the statutes of Pierre d’Ailly, in order to come and hear the sermon.

However, if these good Haudriettes were, for the moment, complying with the statutes of Pierre d’Ailly, they certainly violated with joy those of Michel de Brache, and the Cardinal of Pisa, which so inhumanly enjoined silence upon them.

“What is this, sister?” said Agnes to Gauchère, gazing at the little creature exposed, which was screaming and writhing on the wooden bed, terrified by so many glances.

“What is to become of us,” said Jehanne, “if that is the way children are made now?”

“I’m not learned in the matter of children,” resumed Agnes, “but it must be a sin to look at this one.”

In England, at one time anyway, on the Monday after Low Sunday, between the hours of 9 and noon, there was the strange custom by which men “captured” women (often by lifting them up in chairs) for a ransom which was given to the Church. On Tuesday the women reciprocate by capturing the men. These two days became known as “Hocktide.” This custom has never been explained.

More recently, this Sunday has been called Divine Mercy Sunday.

During the course of Jesus’ revelations to Saint Faustina on the Divine Mercy He asked on numerous occasions that a feast day be dedicated to the Divine Mercy and that this feast be celebrated on the Sunday after Easter. The liturgical texts of that day, the 2nd Sunday of Easter, concern the institution of the Sacrament of Penance, the Tribunal of the Divine Mercy, and are thus already suited to the request of Our Lord. This Feast, which had already been granted to the nation of Poland and been celebrated within Vatican City, was granted to the Universal Church by Pope John Paul II on the occasion of the canonization of Sr. Faustina on 30 April 2000. In a decree dated 23 May 2000, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments stated that “throughout the world the Second Sunday of Easter will receive the name Divine Mercy Sunday, a perennial invitation to the Christian world to face, with confidence in divine benevolence, the difficulties and trials that mankind will experience in the years to come.”

Thomas Sunday is the name of this Sunday in the Eastern Churches. The Sunday after Easter is the Sunday of St. Thomas, also known as Second Sunday or Antipascha (“opposite” Pascha, i.e., at the other end of Bright Week). Historically, this day in the early Church was the day that the newly-baptized Christians removed their robes and entered once again into the life of this world.

This day is also known as Antipascha. This does not mean “opposed to Pascha,” but “in place of Pascha.” Beginning with this first Sunday after Pascha, the Church dedicates every Sunday of the year to the Lord’s Resurrection. Sunday is called “Resurrection” in Russian, and “the Lord’s Day” in Greek. The Orthodox Church dedicates every Sunday of the year to the Lord’s Resurrection starting on this Sunday, the eighth day of the paschal celebration, the last day of Bright Week.

Happy Quasimodo Sunday!