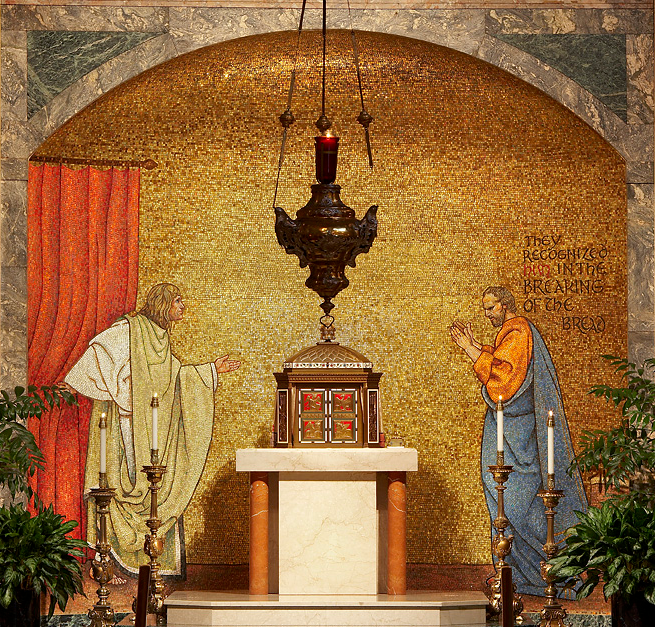

They recognized Him in the Breaking of the Bread

Blessed Sacrament Chapel, St Matthew’s Cathedral, Washington, D.C.

Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Acenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Roman Catholic Parish of

The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Easter III

April 15, 2018

Prelude

Christ lag in Todesbanden, Johann Kaspar Ferdinand Fischer

Hymns

At the Lamb’s high feast we sing (SALZBURG)

Shepherd of souls, refresh and bless (ST AGNES)

Deck thyself, my soul, with gladness (SCHMÜCKE DICH)

Anthems

Surrexit pastor bonus, Tomás Luis de Victoria

Alleluia! Cognoverunt discipuli, William Byrd

Postlude

Allein Gott in der Hoh sei Ehr, Johann Gottfried Walther

Prelude

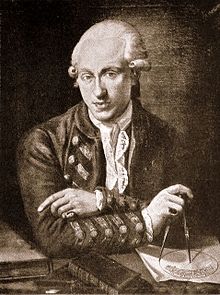

Christ lag in Todesbanden, Johann Kaspar Ferdinand Fischer

Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer (c.1656 – August 27, 1746) was a German Baroque composer. Much of Fischer’s music shows the influence of the French Baroque style, exemplified by Jean Baptiste Lully, and he was responsible for bringing the French influence to German music.

Hymns

At the Lamb’s high feast we sing (SALZBURG)

At the Lamb’s high feast we sing is a translation by the Robert Campbell (1814-1868) of the seventh century Latin hymn, Ad regias agni dapes, which was sung by the newly baptized at Easter when they were first admitted to communion. Our victorious King through His death and resurrection has caused the angel of death to pass over us. We are redeemed by His blood, which opens Paradise to us where we will live forever. The LORD brought Israel out of Egypt through the sea into the promised land by the blood of the Lamb. Jesus through His death brings us through the wilderness of this life by feeding us with Himself, the true manna that comes down from heaven.

1 At the Lamb’s high feast we sing

praise to our victorious King,

who hath washed us in the tide

flowing from his piercèd side;

praise we him, whose love divine

gives his sacred blood for wine,

gives his body for the feast,

Christ the victim, Christ the priest.

2 Where the Paschal blood is poured,

death’s dark angel sheathes his sword;

Israel’s hosts triumphant go

through the wave that drowns the foe.

Praise we Christ, whose blood was shed,

Paschal victim, Paschal bread;

with sincerity and love

eat we manna from above.

3 Mighty victim from the sky,

hell’s fierce powers beneath thee lie;

thou hast conquered in the fight,

thou hast brought us life and light.

Now no more can death appal,

now no more the grave enthral:

thou hast opened paradise,

and in thee thy saints shall rise.

4 Easter triumph, Easter joy,

sin alone can this destroy;

from sin’s power do thou set free

souls new-born, O Lord, in thee.

Hymns of glory and of praise,

risen Lord, to thee we raise;

holy Father, praise to thee,

with the Spirit, ever be.

Raised a Presbyterian, the Edinburgh advocate Robert Campbell joined the Episcopal Church of Scotland. While he was a Scottish Episcopalian (imagine!), he translated this hymn in 1850 and other Latin hymns for relaxation. In 1852, he joined the Roman Catholic Church. Much of his life, both as a Protestant and a Catholic was dedicated to the education of Edinburgh’s poorest children. He authored a report, Past and present treatment of Roman Catholic children in Scotland, by the Board of Supervision for Relief of the Poor (1863).

The hymn Ad regias Agni dapes has a checkered history. It was originally Ad coenam Agni providi a sixth-century Ambrosian hymn, that is, a hymn composed in iambic tetrameter, after the model of the hymns that St. Ambrose had composed after the model of Roman marching songs. This meter is close to the meter of rythm prose and is also easily adopted to music. The hymn was composed when Latin was still a spoken language. For example, it treats stolis albis candidi [bright with white garments] as if it were istolis albis candidi (eight syllables): ist– is how they pronounced st– in the ‘Vulgar Latin’ period. I presume that the Spanish habit of adding a syllable before an s comes form this: Estarbucks. The hymn also used words from Christian Latin, such as coena, the word used for the Last Supper.

- Ad coenam Agni providi,

stolis salutis candidi,

post transitum maris Rubri

Christo canamus principi. - Cuius corpus sanctissimum

in ara crucis torridum,

sed et cruorem roseum

gustando, Dei vivimus. - Protecti paschae vespero

a devastante angelo,

de Pharaonis aspero

sumus erepti imperio. - Iam pascha nostrum Christus est,

agnus occisus innocens;

sinceritatis azyma

qui carnem suam obtulit. - O vera, digna hostia,

per quam franguntur tartara,

captiva plebs redimitur,

redduntur vitae praemia! - Consurgit Christus tumulo,

victor redit de barathro,

tyrannum trudens vinculo

et paradisum reserans. - Esto perenne mentibus

paschale, Iesu, gaudium

et nos renatos gratine

tuis triumphis aggrega. - Iesu, tibi sit gloria,

qui morte victa praenites,

cum Patre et almo Spiritu,

in sempiterna saecula. Amen.

Here is John Mason Neale’s translation:

- The Lamb’s high banquet we await

in snow-white robes of royal state:

and now, the Red Sea’s channel past,

to Christ our Prince we sing at last. - Upon the Altar of the Cross

His Body hath redeemed our loss:

and tasting of his roseate Blood,

our life is hid with Him in God, - That Paschal Eve God’s arm was bared,

the devastating Angel spared:

by strength of hand our hosts went free

from Pharaoh’s ruthless tyranny. - Now Christ, our Paschal Lamb, is slain,

the Lamb of God that knows no stain,

the true Oblation offered here,

our own unleavened Bread sincere. - O Thou, from whom hell’s monarch flies,

O great, O very Sacrifice,

Thy captive people are set free,

and endless life restored in Thee.’ - For Christ, arising from the dead,

from conquered hell victorious sped,

and thrust the tyrant down to chains,

and Paradise for man regains. - We pray Thee, King with glory decked,

in this our Paschal joy, protect

from all that death would fain effect

Thy ransomed flock, Thine own elect. - To Thee who, dead, again dost live,

all glory Lord, Thy people give;

all glory, as is ever meet,

to Father and to Paraclete. Amen.

And so the hymn was sung for a thousand years.

Urban VIII, by Pietro da Cortona (1627)

And then came the Renaissance and Maffeo Barbarini was elected to the papal throne as Urban VIII (reigned 1623-1644). The new liturgical books of Pius V had just been approved, but Urban found the Latin tasteless and inelegant and barbarous. So he and his assistants “improved” the ancient hymns. As one annoyed hymnologist writes: “Ambrose and Prudentius took something classical and made it Christian; the revisers and their imitators took something Christian and tried to make it classical. The result may be pedantry, and sometimes perhaps poetry; but it is not piety.”

So Ad cenam Agni providi in 1632 became Ad regias Agni dapes, the version translated by Campbell. This hymn us used at Vespers from Easter Sunday until Ascension. Notice I say used, because the classicized hymns were not untended to be sung, but recited privately.

Ad regias Agni dapes,

Stolis amicti candidis,

Post transitum maris Rubri,

Christo canamus Principi.2. Divina cuius caritas

Sacrum propinat sanguinem,

Almique membra corporis

Amor sacerdos immolat.3. Sparsum cruorem postibus

Vastator horret Angelus:

Fugitque divisum mare,

Merguntur hostes fluctibus.4. Iam Pascha nostrum Christus est,

Paschalis idem victima:

Et pura puris mentibus

Sinceritatis azyma.5. O vera caeli víctima,

Subiecta cui sunt tartara,

Soluta mortis vincula,

Recepta vitæ praemia.6. Victor subactis inferis,

Trophaea Christus explicat,

Caeloque aperto, subditum

Regem tenebrarum trahit.7. Ut sis perenne mentibus

Paschale Iesu gaudium,

A morte dira criminum

Vitæ renatos libera.8. Deo Patri sit gloria,

Et Filio, qui a mortuis

Surrexit, ac Paraclito,

In sempiterna saecula. Amen.

Dapes, a classical poetic word, is substituted for the Christian coena, obscuring the reference to the Last Supper and to the Eucharist. The original reference to the roasted (torridum) body of Christ , was eliminated, and Victorian commentators, although they understood the reference to the Paschal Lamb, found the image horrifying.

The Benedictines and the Dominicans would have nothing to do with such innovations, and continued to use the original version of the hymn. Their attitude was Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini.

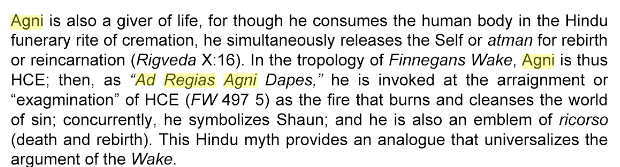

Ad regias agni dapes is mentioned in James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. Here is the context:

Pater patruum cum filiabus familiarum. Or, but, now, and, ariring out of her mirgery margery watersheads and, to change that subjunct from the traumaturgid for once in a while and darting back to stuff, if so be you may identify yourself with the him in you, that fluctuous neck merchamtur, bloodfadder and milkmudder, since then our too many of her, Abha na Lifé, and getting on to dadaddy again, as them we’re ne’er free of, was he in tea e’er he went on the bier or didn’t he ontime do something seemly heavy in sugar? He sent out Christy Columb and he came back with a jailbird’s unbespokables in his beak and then he sent out Le Caron Crow and the peacies are still looking for him. The seeker from the swayed, the beesabouties from the parent swarm. Speak to the right! Rotacist ca canny! He caun ne’er be bothered but maun e’er be waked. If there is a future in every past that is present Quis est qui non novit quinnigan and Qui quae quot at Quinnigan’s Quake! Stump! His producers are they not his consumers? Your exagmination round his factification for incamination of a warping process. Declaim!

—Arra irrara hirrara man, weren’t they arriving in clansdestinies for the Imbandiment of Ad Regias Agni Dapes, fogabawlers and panhibernskers, after the crack and the lean years, scalpjaggers and houthhunters, like the messicals of the great god, a scarlet trainful, the Twoedged Petrard, totalling, leggats and prelaps, in their aggregate ages two and thirty plus undecimmed centries of them with insiders, extraomnes and tuttifrutties allcunct, from Rathgar, Rathanga, Rountown and Rush, from America Avenue and Asia Place and the Affrian Way and Europa Parade and besogar the wallies of Noo Soch Wilds and from Vico, Mespil Rock and Sorrento, for the lure of his weal and the fear of his oppidumic, to his salon de espera in the keel of his kraal, like lodes of ores flocking fast to Mount Maximagnetic, afeerd he was a gunner but affaird to stay away, Merrionites, Dumstdumbdrummers, Luccanicans, Ashtoumers, Batterysby Parkes and Krumlin Boyards, Phillipsburgs, Cabraists and Finglossies, Ballymunites, Raheniacs and the bettlers of Clontarf, for to contemplate in manifest and pay their firstrate duties before the both of him, twelve stone a side, with their Thieve le Roué! and their Shvr yr Thrst! and their Uisgye ad Inferos! and their Usque ad Ebbraios! at and in the licensed boosiness primises of his delhightful bazar and reunited magazine hall, by the magazine wall.

Completely clear, I hope.

A helpful commentary explains:

The tune is SALZBURG, by Jakob Hintze (1622-1702),who in 1666 became court musician to the Elector of Brandenburg at Berlin; but he retired to his birthplace in 1695, and died at Berlin with the reputation of being an excellent contrapuntist.

Here is At the Lamb’s high feast sung at at the most appropriate occasion: Communion at Easter.

Shepherd of souls, refresh and bless (ST AGNES)

Shepherd of souls, refresh and bless was written by the Moravian James Montgomery (1771—1854). As at the supper at Emmaus, Jesus feeds us. As the Good Shepherd, He lays down his life for His sheep, giving them His body and blood as their sustenance so that they may live forever. We know Jesus especially in the breaking of the bread, the action that symbolizes His death by which He sacrifices Himself for us and gives Himself to us.

The hymn is a tissue of Biblical references: we are God’s ”chosen,” the elect, his flock. The Eucharist is “manna in the wilderness” and “water from the rock,” the one that Moses struck and was a type of Christ (I Cor 10:4). The second stanza continues he metaphor of pilgrimage; on earth we are but strangers and travelers (Heb 11:13); the Eucharistic body of the Lord, like the manna in the desert, gives us strength to reach our true home, the Promised Land, where we will abide forever. Like the disciples at Emmaus, we recognize the Lord in the “breaking bread,” (Lk 24:35); we pray that he will not vanish, but spread his table in our hearts and sup with us (Rev 3:20).

Shepherd of souls, refresh and bless

Thy chosen pilgrim flock,

With manna in the wilderness,

With water from the rock.We would not live by bread alone,

But by that word of grace,

In strength of which we travel on

To our abiding-place.Be known to us in breaking bread,

But do not then depart,

Saviour, abide with us, and spread

Thy table in our heart.There sup with us in love divine;

Thy body and Thy blood,

That living bread, that heavenly wine,

Be our immortal food.

Here is Trinity Church singing it.

James Montgomery

James Montgomery (1771-1854) was born at Irvine in Ayrshire, on the western coast of Scotland. He was the son of John Montgomery, the only Moravian pastor in Scotland. The British Moravian church traces its roots back to the Moravian Missionary center in Hernnhut, Germany (Moravians were also known as Hernnhuters or the Bohemian Brethren).

John and his wife felt God’s call to be missionaries to the island of Barbados, in the West Indies. Tearfully, they placed six-year old James in a Moravian settlement at Gracehill in Central Ireland. That was to be the last time James would see them. They died within a year of each other after reaching Barbados.

Left with nothing, James was sent to be trained for the ministry at the Moravian School at Fulneck, near Leeds, England. It was here that he first started writing verse, at the age of 10. At Fulneck, secular studies were banned, but James nevertheless found means of borrowing and reading a good deal of poetry, including Burns’ “Lines To A Mountain Daisy.” He made ambitious plans to write epics of his own.

He suffered periods of deep depression as a result of losing his parents at such an early age. The Moravians who were trying to care for the orphan found him to be a dreamer, who “never had a sense of the hour.” Failing school at the age of 14, they “put him out to business” to a baker in Mirfield, just seven miles to the south. James left on his own and hired himself out to a storekeeper at Wath-upon-Dearne, another thirty miles to the south. Not finding much to his liking, James ran away again, wondering from place to place, trying to sell his freshly written verses. After further adventures, including an unsuccessful attempt to launch himself into a literary career in London, he moved to Sheffield in 1792 to become assistant to Joseph Gales, auctioneer, bookseller and printer of the Sheffield Register. In 1794, Gales left England to avoid political prosecution and Montgomery took the paper in hand, changing its name to the Sheffield Iris. Now owning the paper, he was able to publish his writings as he pleased.

These were times of political repression and he was twice imprisoned on charges of sedition. The first time was in 1795 for printing a poem celebrating the fall of the Bastille; the second in 1796 was for criticizing a magistrate for forcibly dispersing a political protest in Sheffield. His later account of this episode was published in 1840. Turning the experience to some profit, in 1797 he published a pamphlet of poems written during his captivity, as Prison Amusements. For some time, the Iris was the only newspaper in Sheffield; but beyond the ability to produce fairly creditable articles from week to week, Montgomery was devoid of the journalistic faculties which would have enabled him to take advantage of his position. Other newspapers arose to fill the place which his might have occupied and in 1825 he sold it on to a local bookseller, John Blackwell.

In his youth, he had strayed from the church, but at his own request he was readmitted into the Moravian congregation at Fulneck when forty-three years of age. He expressed his feelings at the time in the following lines

People of the living God,

I have sought the world around,

Paths of sin and sorrow trod,

Peace and comfort nowhere found.

Now to you my spirit turns–

Turns a fugitive unblest;

Brethren, where your altar burns,

O receive me into rest.

Thereafter he became an avid worker for missions and an active member of the Bible Society. He was interested in social issues and the missions. He attacked attacking the lottery (then, as now, a way of extracting money from the desperate poor) in Thoughts on Wheels (1817) and taking up the cause of the chimney sweeps’ apprentices in The Climbing Boys’ Soliloquies. His next major poem was Greenland (1819), a poem in five cantos of heroic couplets. This was prefaced by a description of the ancient Moravian church, its eighteenth-century revival and mission to Greenland in 1733.

In addition to Shepherd of souls (1940 Hymnal, #213), his hymns Angels from the realms of glory (1940 Hymnal, #28) and Hail to the Lord’s Anointed (1940 Hymnal, #545) are still sung.

In 1861, a monument designed by John Bell (1811–1895) was erected over his grave in the Sheffield cemetery at a cost of £1000, raised by public subscription on the initiative of the Sheffield Sunday School Union, of which he was among the founding members. On its granite pedestal is inscribed: “Here lies interred, beloved by all who knew him, the Christian poet, patriot, and philanthropist. Wherever poetry is read, or Christian hymns sung, in the English language, ‘he being dead, yet speaketh’ by the genius, piety and taste embodied in his writings.” There are also extracts from his poems “Prayer” and “The Grave”. After it fell into disrepair the statue was moved to the precinct of Sheffield Cathedral in 1971, where there is also a memorial window.

Elsewhere in Sheffield there are various streets named after Montgomery and a Grade II-listed drinking fountain on Broad Lane. The meeting hall of the Sunday Schools Union (now known as The Montgomery), in Surrey Street, was named in his honour in 1886; it houses a 420-seat theater which also bears his name. Elsewhere, Wath-upon-Dearne, flattered by being called “the queen of villages” in his work, has repaid the compliment by naming after him a community hall, a street and a square. His birthplace in Irvine was renamed ‘Montgomery House’ after he paid the town a return visit in 1841 but has since been demolished. Sic transit.

Deck thyself, my soul, with gladness (SCHMÜCKE DICH)

Deck thyself, my soul, with gladness. The original German text, Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele, was written by the German politician and poet Johann Franck (1618—1677) in the aftermath of the Thirty Years’ War. It expresses an intimate relationship between the individual believer and his Savior, Jesus Christ. Jesus, ascended into heaven, is still present as our food in this “wondrous banquet.” He is the fount, from whom our being flows as we receive Him and are filled with Him. He feeds us and transforms us into His likeness so that we become His joy and boast and glory before the heavenly court.

Deck thyself, my soul, with gladness,

leave the gloomy haunts of sadness;

come into the daylight’s splendour,

there with joy thy praises render

unto him whose grace unbounded

hath this wondrous banquet founded:

high o’er all the heavens he reigneth,

yet to dwell with thee he deigneth.Sun, who all my life dost brighten,

light, who dost my soul enlighten,

joy, the sweetest heart e’er knoweth,

fount, whence all my being floweth,

at thy feet I cry, my Maker,

let me be a fit partaker

of this blessed food from heaven,

for our good, thy glory, given.Jesus, Bread of Life, I pray thee,

let me gladly here obey thee;

never to my hurt invited,

be thy love with love requited:

from this banquet let me measure,

Lord, how vast and deep its treasure;

through the gifts thou here dost give me,

as thy guest in heaven receive me.

Here is the Schola Cantorum of St. Peters-in-the-Loop singing the hymn. Here is the Hastings Choir.

Here is the 1674 text.

1. Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele!

Laß die dunckle Sünden Höle!

Komm ans helle Licht gegangen;

Fange herrlich an zu prangen.

Denn der Herr voll Heyl und Gnaden,

Wil dich itzt zu Gaste laden,

Der den Himmel kan verwalten,

Wil itzt Herberg’ in dir halten.2. Eile, wie Verlobten pflegen,

Deinem Bräutigam entgegen,

Der da mit dem Gnaden-Hammer

Klopfft an deine Hertzens-Kammer.

Oeffn’ ihm bald die Geistes-Pforten:

Red ihn an mit schönen Worten:

Komm, mein Liebster, laß dich küssen!

Laß mich deiner nicht mehr missen.3. Zwar in Kauffung theurer Wahren

Pflegt man sonst kein Geld zu sparen:

Aber du wilt für die Gaben

Deiner Huld kein Geld nicht haben:

Weil in allen Bergwercks-Gründen

Kein solch Kleinod ist zu finden,

Daß die Blut-gefüllte Schaalen

Und dis Manna kan bezahlen.4. Ach! wie hungert mein Gemüthe,

Menschen-Freund, nach deiner Güte!

Ach! wie pfleg’ ich offt, mit Thränen,

Mich nach de iner Kost zu sehnen!

Ach! wie pfleget mich zu dürsten,

Nach dem Tranck des Lebens-Fürsten!

Wünsche stets daß mein Gebeine

Sich durch Gott mit Gott vereine.5. Beydes Lachen und auch Zittern

Lässet sich in mir itzt wittern:

Das Geheinmiß dieser Speise,

Und die unerforschte Weise,

Machet daß ich früh vermercke,

Herr, die Grösse deiner Stärcke!

Ist auch wohl ein Mensch zu finden

Der dein’ Allmacht solt ergründen?6. Nein! Vernunfft die muß hier weichen,

Kan dieß Wunder nicht erreichen:

Daß diß Brodt nie wird verzehret,

Ob es gleich viel tausend nehret;

Und daß mit dem Safft der Reben

Uns wird Christi Blut gegeben.

O der grossen Heimligkeiten

Die nur Gottes Geist kan deuten!7. Jesu, meine Lebens-Sonne!

Jesu, meine Freud’ und Wonne!

Jesu, du mein gantz Beginnen,

Lebens-Quell und Licht der Sinnen!

Hier fall ich zu deinen Füssen!

Laß mich würdiglich gemessen

Dieser deiner Himmels-Speise,

Mir zum Heyl, und dir zum Preise!8. Herr, es hat dein treues Lieben

Dich vom Himmel abgetrieben,

Daß du willig hast dein Leben

In den Tod für uns gegeben,

Und darzu gantz unverdrossen,

Herr, dein Blut für uns vergossen,

Das uns itzt kan kräfftig träncken,

Deiner Liebe zu gedencken!9. Jesu wahres Brodt des Lebens!

Hilff, daß ich doch nicht vergebens,

Oder mir vielleicht zum Schaden

Sey zu deinem Tisch geladen!

Laß mich durch diß Seelen-Essen

Deine Liebe recht ermessen,

Daß ich auch, wie itzt auf Erden,

Mag dein Gast im Himmel.

The erotic imagery in the German was eliminated by Catherine Winkworth when she translated the hymn for her Lyra Germanica.

The original 1674 German text was written by

Johann Franck

Johann Franck (1618-1677. He was German poet, lawyer and public official. After his father’s death in 1620, Franck’s uncle by marriage, the town judge, Adam Tielckau, adopted him and sent him to schools in Guben, Cottbus, Stettin, and Thorn. On June 28, 1638, he enrolled at the University of Königsberg to study jurisprudence. This was the only German university left undisturbed by the Thirty Years’ War. Here his religious spirit, his love of nature, and his friendship with such men as the his poetic mentor, Simon Dach and Heinrich Held, preserved him from sharing in the excesses of his fellow students.

Johann Franck returned to Guben at Easter 1640, at his mother’s urgent request; she wished to have him near her in those times of war when Guben frequently suffered from the presence of both Swedish and Saxon troops. After his return from Prague, in May 1645, Franck embarked on a distinguished civic career as attorney, city councillor (1648) and Burgermeister (Mayor) (1661), and in 1671 (or 1670) was appointed as county elder of Guben in the margravate (Landtag – Diet)) of Lower Lusatia.

Johann Franck wrote both secular and religious poetry and published his first work, Hundertönige Vaterunsersharfe, at Guben in 1646. Almost his entire output is brought together in the two-volume Teutsche Gedichte. The first part, Geistliches Sion (Guben, 1672), contains 110 religious songs, provided with some 80 melodies. Bach composed 14 settings of seven of his texts, the most famous being the motet Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227.

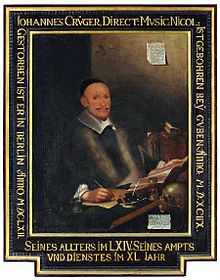

Johann Crüger

The chorale melody associated with this text was composed by the German Lutheran theologian and musician, Johann Crüger (1598-1662). After passing through the schools at Guben, Sorau and Breslau, the Jesuit College at Olmütz, and the Poets’ school at Regensburg, he made a tour in Austria, and, in 1615, settled at Berlin. There, save for a short residence at the University of Wittenberg, in 1620, he employed himself as a private tutor till 1622. In 1622 he was appointed Cantor of St. Nicholas’s Church at Berlin, and also one of the masters of the Greyfriars Gymnasium. He died at Berlin Feb. 23, 1662. Crüger wrote no hymns, although in some American hymnals he appears as “Johann Krüger, 1610,” as the author of the supposed original of C. Wesley’s “Hearts of stone relent, relent”. He was one of the most distinguished musicians of his time. Of his hymn tunes, some 20 are still in use, the best known probably being that to “Nun danket alle Gott”, which is set to No. 379 in Hymns Ancient & Modern.

Anthems

Surrexit pastor bonus, Tomás Luis de Victoria

Surrexit pastor bonus qui animam suam posuit pro ovibus suis, et pro grege suo mori dignatus est, alleluia.

The good shepherd has arisen, who laid down his life for his sheep, and for his flock deigned to die, alleluia.

____________________________________

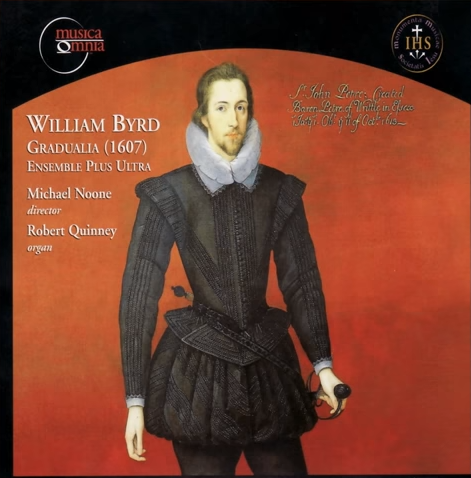

Alleluia! Cognoverunt discipuli, William Byrd

Allein Gott in der Hoh sei Ehr, Johann Gottfried Walther

Ronald IJmker (yes, that is how it is spelled) plays in the Hervormde Kerk in Coevorden.

Johann Gottfried Walther

Johann Gottfried Walther (18 September 1684 – 23 March 1748) was a German music theorist, organist, composer, and lexicographer of the Baroque era.

Walther was born at Erfurt. Not only was his life almost exactly contemporaneous to that of Johann Sebastian Bach, he was the famous composer’s cousin.

Walther was most well known as the compiler of the Musicalisches Lexicon (Leipzig, 1732), an enormous dictionary of music and musicians. Not only was it the first dictionary of musical terms written in the German language, it was the first to contain both terms and biographical information about composers and performers up to the early 18th century. In all, the Musicalisches Lexicon defines more than 3,000 musical terms; Walther evidently drew on more than 250 separate sources in compiling it, including theoretical treatises of the early Baroque and Renaissance. The single most important source for the work was the writings of Johann Mattheson, who is referenced more than 200 times.

Some further information on Walther can be found in the book Musica Poetica by Dietrich Bartel. Bartel quotes Walther’s definition of musica poetica, or musical rhetoric, as:

“Musica Poetica or musical composition is a mathematical science through which an agreeable and correct harmony of the notes is brought to paper in order that it might later be sung or played, thereby appropriately moving the listeners to Godly devotion as well as to please and delight both mind and soul…. It is so called because the composer must not only understand language as does the poet in order not to violate the meter of the text but because he also writes poetry, namely a melody, thus deserving the title Melopoeta or Melopoeus.”

Walther was the music teacher of Prince Johann Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar. He wrote a handbook for the young prince with the title Praecepta der musicalischen Composition, 1708. It remained handwritten until Peter Benary’s edition (Leipzig, 1955). As an organ composer, Walther became famous for his organ transcriptions of orchestral concertos by contemporary Italian and German masters. He made 14 transcriptions of concertos by Albinoni, Gentili, Taglietti, Giuseppe Torelli, Vivaldi and Telemann. These works were the models for Bach to write his famous transcriptions of concertos by Vivaldi and others. On the other hand, Walther as a city organist of Weimar wrote exactly 132 organ preludes based on Lutheran chorale melodies. Some free keyboard music also belongs to his legacy.