Effingham Lawrence (March 2, 1820- December 9, 1878) was born in Queens, the son of Effingham Lawrence and Anne Townsend, and the brother of Joseph Effingham Lawrence, Lydia Lawrence, and Henry Effingham Lawrence. He was my wife’s third great grand uncle.

He married Jane Lucretia Osgood (April 1, 1829- 3 March 1863), a Kentucky heiress, on June 17, 1847. They had six children, one of whom married a Gilman, a name known at Johns Hopkins University (as we shall see).

Like his brothers, Effingham left New York. After his marriage he bought Magnolia Plantation in Plaquemines Parish, on the Mississippi, abut fifty miles below New Orleans. He served as a representative in the Louisiana legislature 1854-1855.

Two river boat pilots and occasional pirates, George Bradish and William Johnson, had noticed that the land about fifty miles south of New Orleans had some elevation, and in 1780 established Magnolia plantation to raise and process sugar. It is said that Jean Lafitte, the pirate, was a friend of Bradish and Johnson and a frequent guest at Magnolia. Johnson had a son, Bradish Johnson, who spent six months each year on Fifth Avenue in New York and married Louisa Ann Lawrence of Bayside, New York, a cousin of Effingham’s. But more about them in a later blog.

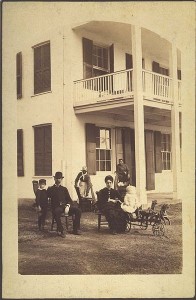

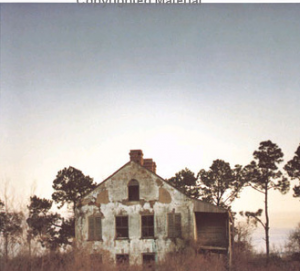

The house at Magnolia Plantation was built in 1795; it had two stories and 10 rooms, each 22 by 28 feet. The walls were two and a half feet thick, plaster over brick.

Magnolia Plantation

Effingham lived the comfortable life of a wealthy plantation owner, surrounded by the slaves who were, he thought, loyal to their considerate master. Abolitionists could not conceive of how well cared for and content the blacks were – so the owners thought.

After the slaves at Magnolia and Woodland Plantations had worked hard to fill a crevasse in the levee and to save the crops, Lawrence invited the owners and slaves from both plantations to a celebration at Magnolia. In October 1856 a letter to the Picayune reported:

At 12 o’clock the whole party met in the church of Magnolia Plantation…Hymns and psalms were sung to the Almighty by all present, accompanied by the melodious tomes of the organ. But, Mr. Editor, it would have pleased you to have heard the psalm (commonly known as the “old Hundred”) sung by nearly six hundred voices. After the exercises at church, the party repaired to a sumptuous table, where everything had been prepared, and there nearly 450 negroes, men and women, partook of the dinner, Messrs. Lawrence and Decker and their friends attending on them.

Would to God that Wilson, Slade, Giddings and others [presumably abolitionists] would have been present to judge for themselves how we Louisiana planters treat the negroes under our care! After dinner the negroes retired to a place prepared for the occasion, where, at the sound of the banjo and tambourine, they danced those amusing but touching dances which we alone, who have witnessed them from our youth, can appreciate.

Such was the quasi-feudal arrangement as the planters imagined it, even showing their gratitude to their “hands” by waiting on them themselves on special occasions. The white writers went to pains to avoid the word slaves, Instead they spoke of hands, negroes, servants, workers, etc.

George Hamill, a northerner, in 1860 worked on the Mississippi clearing obstructions. There he had a mixed experience with Effingham:

I proceeded at once to my place of destination, a plantation 46 miles below the city called “Magnolia Place” and owned by E. Lawrence, containing over 1000 acres of improved land with nearly 200 Negroes, with a large sugar mill and machinery for making sugar. Nearly the whole of the plantation is devoted to raising sugar cane, and last year he made over 1400 hogshead of sugar, beside a large quantity of molasses, and one of the finest sights a person ever saw in a large sugar plantation in the month of June and July when the cane is as high as a man’s head, and when the wind blows it reminds you of the waves of the ocean, excepting the color which is a beautiful green. The Negroes are well dressed, well fed, and well taken care of. The planter has a physician hired by the year who visits the sick daily, also a preacher who preaches to them every Sunday, and I think they are the most happy and contented race of beings I ever saw. My business in coming south was to put up 2 dredging machines for digging canals on the plantation; invented and built by I. C. Osgood of Troy, N. Y. I built and put up the machines without any trouble and concluded to stay in the South a year to see if it would improve my health. I worked on the plantation 18 months, and had a difficulty with E. Lawrence which resulted in my leaving the plantation. After a great deal of trouble I succeeded in obtaining a settlement all in their favor, cheating me out of some $300.00. I saw how the thing was going. I concluded to take what I could get, and go home, if possible.

As Hamill was a northerner, his testimony about Lawrence’s care for his slaves is reliable. As far as it could be in a condition of servitude, life on this plantation was decent for the slaves, although they worked hard (which they would have had to do as free laborers also).

The War for Southern Independence

The sugar planters of Louisiana led the movement for secession. On December 27, 1860 Effingham addressed a meeting of the Friends of Southern Rights and Separate State Secession. He

dwelt upon the long forbearance of the South under alleged Northern provocation, claiming that it was the right and duty of the region to “stand to her honor”….”the duty of Louisiana and every citizen thereof,” cried the great cane planter, “ is to stand and defend Louisiana through fire and blood if necessary.” He little realized the prophecy of his words.

Louisiana Secession Convention, Baton Rouge

Effingham was the delegate for Plaquemines Parish and opened the secession convention on January 23, 1861 in Baton Rouge. He signed the ordinance of secession on January 26, 1861 and moved that all those who signed be given golden pens to commemorate their role. Effingham, unlike other planters, contributed liberally to the Bienville Guards of Plaquemine Parish. However, he did not enlist (he was in his early forties), and in the disastrous aftermath of the war, his role was sometimes remembered with bitterness by those who had suffered in the war.

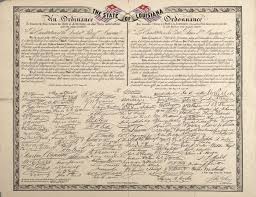

Ordinance of Secession

In the North the Lawrences had been Quakers and involved in manumission, although not in abolition. Effingham, it was remembered by Louisianans, was a transplanted Northerner. Perhaps he was so outspoken to convince people that he identified with the South; perhaps as a sugar planter he had internalized the attitudes of all planters.

The Union navy went up the Mississippi; the slaves gathered on the levees and cheered, the plantation owners were glum, and many abandoned their plantations

This inspired the abolitionist Henry Work to write this in 1862:

The Year of Jubilo

Say, darkies, hab you seen de massa, wid de muffstash on his face,

Go long de road some time dis mornin’, like he gwine to leab de place?

He seen a smoke way up de ribber, whar de Linkum gunboats lay;

He took his hat, and lef’ berry sudden, and I spec’ he’s run away!

CHORUS:

De massa run, ha, ha! De darkey stay, ho, ho!

It mus’ be now de kingdom coming, an’ de year ob Jubilo!

He six foot one way, two foot tudder, and he weigh tree hundred pound,

His coat so big, he couldn’t pay the tailor, an’ it won’t go halfway round.

He drill so much dey call him Cap’n, an’ he got so drefful tanned,

I spec’ he try an’ fool dem Yankees for to tink he’s contraband.

CHORUS

De darkeys feel so lonesome libbing in de loghouse on de lawn,

Dey move dar tings into massa’s parlor for to keep it while he’s gone.

Dar’s wine an’ cider in de kitchen, an’ de darkeys dey’ll have some;

I s’pose dey’ll all be cornfiscated when de Linkum sojers come.

CHORUS

De obserseer he make us trouble, an’ he dribe us round a spell;

We lock him up in de smokehouse cellar, wid de key trown in de well.

De whip is lost, de han’cuff broken, but de massa’ll hab his pay;

He’s ole enough, big enough, ought to known better dan to went an’ run away.

(Some consider the dialect insulting to blacks, but the slave owners are the real target, with a little slap at the Yankee soldiers. The song was very popular among blacks, especially black volunteers in the Union army, and was played by their regimental bands. Lev. 25 defines rules for the people of Israel regarding the treatment of slaves – “The year of Jubilee” equals the end of a period of time and decrees that a slave and all his family must be set free – i.e.. “Redeemed” This concept easily dovetails with the concept of the coming Messiah who will redeem Israel and all nations. The Union soldiers didn’t know what the legal status of the slaves who fled to them was, so they called them “contraband.” Here is a great 1927 rendition. )

The Union army quickly occupied part of Louisiana, and its presence disrupted the economy of the plantations, even before the Emancipation Proclamation. Effingham unlike those owners who ran away, stayed, although he sent his family to New Orleans for safety; his wife died there in March 1863. Magnolia Plantation was affected by the war (although apparently less than other places). The overseer pronounced that the slaves had a severe case of Lincolnitis (a disease similar to the drapetomania diagnosed by Dr. Cartwright). Some slaves ran away, but after having experienced the chaos of the Union camps, decided to return to Magnolia to wait for the outcome of the war.

The Magnolia Plantation overseer applied on 14 June 1862 to the Union Authorities at Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip to collect his workers and take them back to their cabins. The Federal Commander, doubtless happy to be rid of the responsibility of providing for great numbers of indolent blacks, gave their consent (Journal – 14 June 1862.)

In October 1862 Effingham wrote that discipline was eroding:

we have a terrible state of affairs Here, negroes refusing to work and women all in there Houses.

The slaves erected a gallows in their quarters. They explained that a Union officer had told them to do that to drive their master off the plantation. Lawrence worried:

“Hang their master & and that then they will be Free. No one can tell what a Day may bring Forth – we are all in a State of Great uneasiness.”

Violence was in the air, but there was no insurrection, as had happened in Haiti and had threatened under Nat Turner. Perhaps slaves were content to let the white men kill each other and await the outcome of the war.

Lawrence’s overseer did not like the Yankees. He wrote this prayer, somewhat lacking in thr spirit of forgiveness, during the war (original spelling):

This day is set a part by President Jefferson DAVIS for fasting and praying owing to the deplorable condishions over Southern country is in my prayer Sincerely to God is that Every Black Republican in the Hole combined whorl Either man woman o chile that is opposed to negro slavery as it existed in the Southern Confederacy shal be trubled with pestilence & calamitys of all kinds & drag out the balance of their existence in misry (&) degradation with scarsely food (&) rayment enough to keep sole (&) body to gether and O God I pray the to direct a bullet or a bayonet to pirce the hart of every northern Soldier that invades southern Soil (&) after the body has Rendered up its tralerish Soul gave it a trators reward a birth in the Lake og fires (&) Brimstone My honest convicksion is that Every man women (&) child that has gave aid to the abolishionist are fit Subjects for Hell I all so ask the aid the Southern confedercy in maintaining ower rites (&) establishing the confederate Goverment Believing in this case the prares from the wicked will prevailth much – Amen –

Lawrence, however, adapted with the changing time. His slaves grew restless and refused to work unless they were paid. Lawrence told them they were still his slaves, and he would not pay them, but he promised

a Handsome Present Provided they Resisted the Pressure that is now Felt everywhere by the Slaves to run away and Leave there Home for the Forts and Federal Camps.

He kept his promise and gave them $2,500.

He warned his slaves that in the Union camps they would find

Nothing but Degradation Misssery & Death and it was for there Interest to Remain and to be taken Care off Rather than to Leave there Good Houses and Suffer as was Sure to Do to an immense extent.

The Union army was not prepared to care for the runaway slaves, and conditions ranged from poor to terrible. Many Northerners were racists, and others hated blacks as the cause of the war.

Two abolitionists, Hepworth and Wheeler, who visited Magnolia Plantation in 1863, were satisfied with what they saw. They reported that Lawrence’s former slaves were now

all at home, working cheerfully at their tasks, under the incentive of kindness, promises honestly kept, and of the prospective reward of one-fifteenth of the crop

which was more than the Union army required to be given to ex-slaves.

Attempts at Reconciliation

Effingham, who seems to have been generally respected and liked (except by the most die-hard Confederates), offered hospitality to Union officers. He became a friend of General Sheridan, and was appointed to the levee committee. The Lawrences believed in being flexible; their political model was the reed and not the oak. The Lawrences had served both the Dutch and English governments in New York; Effingham voted for secession and then befriended the Union occupiers.

But not everyone was happy with the Occupation. Opponents of Reconstruction in Louisiana organized the White League. It was a public, para-military force set up to rid the state of carpetbaggers. It claimed it had no animosity to blacks (who did not believe that protestation).

Dr. Taylor wrote to the newspapers to explain the aims of the White League: to gain control of Louisiana and to deny employment to uncooperative blacks.

Dr. Taylor wrote to the newspapers to explain the aims of the White League: to gain control of Louisiana and to deny employment to uncooperative blacks.

Effingham write a long public letter (Picayune, August 23, 1874) condemning this attempt effectively to disenfranchise blacks.

Lawrence admitted that the newly enfranchised black voters had elected corrupt carpetbaggers. The black voters saw the corruption of the white men they had voted for, and were disappointed in their supposed friends; the carpetbaggers then blamed the negro voters for the corruption, thus turning blacks again whites and whites against blacks. Lawrence pointed out that whites also were known to make bad political decisions:

Such lapses in citizenship have occurred among the Anglo-Saxon citizens, and will occur again; but they are not incurable in their character, nor in either the white or black race, such as to lead the patriot to despair of the Republic.

Lawrence attacked the “scarecrow” of social equality (which seems to have been a code word for miscegenation).

In exceptional cases I have seen white men who, of choice, sought negro association, and negroes who preferred the association of whites; but as the rule, with scarcely an exception, the healthy minded white and colored alike seek domestic affiliations with those of their own race.

He condemned the attempt to pit white against black:

In my judgment a race organization, political in its character, white or black, is at all times questionable and dangerous. But at this juncture of affairs is evil, only evil, and full of mischief to both races and to the State.

The New York Times in recounting Lawrence’s letter, said that it was sure that many responsible Louisianans were ashamed of the White League, but Lawrence was

the only one of large influence who has entered his formal protest against a course which can only end in disaster to the reckless men engaged in it.

Lawrence was insulted, mobbed in the streets, and ordered to leave the state.

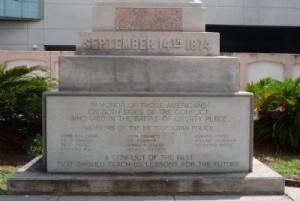

The Battle of Liberty Place

Under former Confederate officers the White League drilled and trained forces until they were better prepared than the police and the state militia. They smuggled in arms, cut telegraph lines to the North, and staged a coup d’état. On September 14, 1874 in heavy street fighting 5,000 members of the League defeated 3,500 police and militia, with 100 casualties (the Battle of Liberty Place). The Republican Governor Kellogg fled for safety to a federal installation. The White League took over all government offices at bayonet point and evicted all incumbents. But President Grant would not tolerate a rebellion; he sent in Federal troops to restore Kellogg.

In 1891 New Orleans built a monument to the Battle of Liberty Place – it has been moved to an obscure location and may be demolished.

In 1932 a plaque was added:

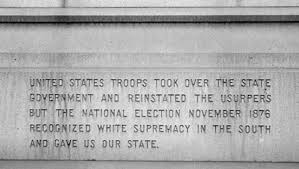

“McEnery and Penn having been elected governor and lieutenant-governor by the white people were duly installed by this overthrow of carpetbag government, ousting the usurpers, Governor Kellogg (white) and Lieutenant-Governor Antoine (colored). United States troops took over the state government and reinstated the usurpers but the national election of November 1876 recognized white supremacy in the South and gave us our state.”

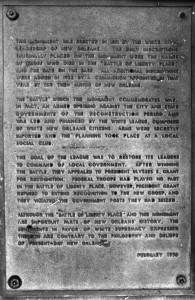

In 1974 the city added a plaque instructing the citizenry to disregard previous plaques:

“Although the “Battle of Liberty Place” and this monument are important parts of the New Orleans history, the sentiments in favor of white supremacy expressed thereon are contrary to the philosophy and beliefs of present-day New Orleans.”

The 1993 inscription that covers the 1932 inscription tries to have it both ways.

In honor of those Americans on both sides of the conflict who died in the Battle of Liberty Place.

A conflict of the past that should teach us lessons for the future.

But what are the lessons?

The Great Train Race

1870 Express Train

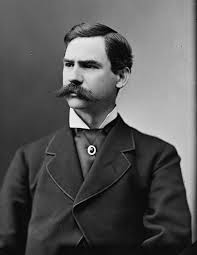

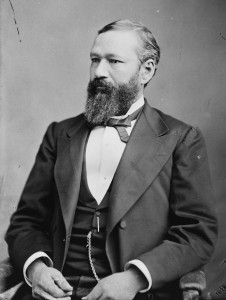

Louisiana politics have always been a contact sport. Governor Warmoth (elected at age 26), a close friend of Effingham’s, and his Lieutenant Governor Pinchback were both Republicans, but belonged to different factions.

Henry Clay Warmoth

Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback

In September 1872 Governor Warmoth and Effingham Lawrence went to New York to discuss railroad matters. At 5 PM one evening at the Fifth Avenue Hotel Warmoth unexpectedly ran into his Lieutenant Governor, Pinchback, who said that he was in North giving speeches. The two agreed to meet at 9 PM that evening to make arrangements to return to New Orleans on the same train.

But Pinchback did not show up, and Warmoth went to bed that night with an uneasy feeling. The next morning he went to the hotel and ran into a young man who was travelling with Pinchback, who said that Pinchback hadn’t returned but his luggage was still at the hotel. Warmoth was still uneasy. He ran into Senator Harris, an acquaintance of Pinchback’s, and asked him whether he had seen Pinchback. Harris said that Pinchback had left on the train for Pittsburgh the previous evening. Warmoth immediately spotted Pinchback’s deception and realized he must be up to something.

He and Lawrence opened telegraphic connections all along the route to New Orleans and took the lightning train south. Pinchback had a twelve hour lead. At Louisville Warmoth and Lawrence learned what Pinchback was up to.

What Pinchback had been doing in New York was conspiring with the Grant faction at achieve a coup d’état in Louisiana to make sure the state delivered its electoral votes to Grant. Pinchback’s supporters in the legislature were waiting for him at Amite, just inside the Louisiana line. There they would

impeach the Governor, Auditor, and some other officers, overturn the city government, reorganize the police, remove all of Warmoth’s appointees throughout the State, especially the registrar of voters, sign the new bills, and continue in session until January next.

They had prepared

plenty of troops to call to protect the coup d’état and maintain by force the raw regime.

The matter was urgent. Warmoth and Lawrence chartered a special train to meet them at Humboldt: the best locomotive of the Mississippi Central and one car. They telegraphed ahead for the track to be cleared the whole distance south. They told the engineer to open the throttle, but he insisted that Lawrence first sign a bond to be responsible for any damages. Meanwhile Warmoth and Lawrence arranged a little trick of their own.

Pinchback was on the train as it stopped in Canton, Mississippi. A man boarded and asked whether there was a Mr. Pinchback aboard. Pinchback identified himself, and was told there was a telegram at the station office for him but it was to be put direct into the hands of Pinchback and no one else. Pinchback went to the station and the stationmaster said he needed positive identification. Pinchback rounded up some people who knew him, and then the stationmaster said he had misplaced the telegram and had to search for it. He finally gave it to Pinchback who tore it open only to discover a blank piece of paper. He then realized what had happened and tried to get out but the door was locked. He tried the window and that was locked. He yelled and finally got someone outside to unlock the door. But then he saw the train two hundred yards down the track on the way to New Orleans. It did not stop as he waved his handkerchief and yelled. He was told there would be another train in the morning, so he spent the night in the town.

At dawn he went to the platform and saw a train approaching.

The tall figure of Governor Warmoth is seen on the platform, and his strong voice is heard shouting – “Hurra! Hulloa! Pinch, is that you? Thought you were with your baggage at the Fifth Avenue. Get aboard and we will take you to the city.”

Warmoth and Lawrence then unfolded the whole counterplot. Pinchback admitted

“you have won another race, and I’ll be d—d if it isn’t the biggest one you ever did or ever will win.”

As their train passed Amite, Louisiana, they saw on the platform the Grant politicians. Pinchback pointed to Warmoth and said, “Captured! Captured!” Warmoth

rose and affectionately and gracefully waved his handkerchief toward the foiled and disgusted conspirators.

Warmoth and Effingham held court in the St. Charles hotel to receive congratulations in their success on thwarting the Grantites – but, of course, that was not the last move in the game.

Congressman for a Day

The 1872 election in which Lawrence (D) ran against Jacob Hale Sypher (R) saw the usual irregularities. Sypher was declared the winner, but Lawrence asked to be seated. The Republican-dominated House investigated, and to show it was not partisan, awarded the seat to Lawrence – on the last day of the session. Lawrence was sworn in at 9:30 AM, March 3, 1875, and drew his pay. His term expired when the House adjourned that evening. It was the first time since the War that a Democrat had won a congressional election in Louisiana.

President Rutherford B. Hayes, over the objections of Republicans who wanted the spoils to go only to Republicans, appointed the Democrat Lawrence to the post of Collector of Customs for the Port of New Orleans.

Effingham seems to have been a genuinely amiable person, and even those on the other side of the political fence liked him.

Moonlight and Magnolias

Effingham made satisfactory arrangements with his former slaves. Some bought small plots form him; others stayed on as workers and were paid. He brought in steam equipment, the first steam plows in Louisiana.

Horace Greeley visited Magnolia Plantation in 1877:

The “Magnolia” plantation of Mr. Lawrence is a fair type of the larger and better class; it lies low down to the river’s level, and seems to court inundation. Stepping from the wharf, across a green lawn, the sugar-house first greets the eye, an immense solid building, crammed with costly machinery. Not far from it are the neat, white cottages occupied by the laborers; there is the kitchen where the field-hands come to their meals; there are the sheds where the carts are housed, and the cane is brought to be crushed; and, ranging in front of a cane-field containing many hundreds of acres, is a great orange orchard, the branches of whose odorous trees bear literally golden fruit; for, with but little care, they yield their owner an annual income of $25,000.

The massive oaks and graceful magnolias surrounding the planter’s mansion give grateful shade; roses and all the rarer blossoms perfume the air; the river current hums a gentle monotone, which, mingled with the music of the myriad insect life, and vaguely heard on the lawn and in the cool corridors of the house, seems lamenting past grandeur and prophesying of future greatness. For it was a grand and lordly life, that of the owner of a sugar plantation; filled with culture, pleasure, and the refinements of living;—but now!

Afield, in Mr. Lawrence’s plantation, and in some others, one may see the steam-plough at work, ripping up the rich soil. Great stationary engines pull it rapidly from end to end of the tracts; and the darkies, mounted on the swiftly rolling machine, skillfully guide its sharp blades and force them into the furrows. Ere long, doubtless, steam-ploughs will be generally introduced on Louisiana sugar estates.”

Effingham seemed to prosper but in 1873 sold a half-interest in the plantation to his friend Warmoth.

Among the last Lawrence family events at the plantation was the wedding of his daughter Bessie Amelia to Arthur Coit Gilman, on Christmas Eve, 1877.

For a full quarter of a mile the river bank was thickly dotted with bonfires, while through the orange grove, which separated the mansion from the Mississippi, twinkled numberless lights. Hundreds of negroes, many of whom weed to be Colonel Lawrence’s slaves, were scattered along the river bank and through the grounds, all of them in the jolliest mood. Of course the bride was lovely, and all the appointments of the wedding most elaborate, but the distinguishing feature of the affair, after all, was the heart participation of the colored people. Just back at the mansion they were served a sumptuous banquet, and when the feast was over, they sang the old plantation songs and danced the old plantation dances with even more vim and enjoyment than I the old days. Altogether the midnight scene was one that would have been worth travelling a good way to see – the brilliantly lighted mansion, with the best of Louisiana society at its windows and on the galleries, hundreds of happy negroes dancing and singing on the green, and in the background the negro cabins, the sugar houses and the orange grove, all beautified by the light of the full moon.

Effingham died at Magnolia on December 9, 1878. He was buried in Greenwood Cemetery, New Orleans.

The Last Chapter

The Warmoth family at Magnolia Plantation c. 1880

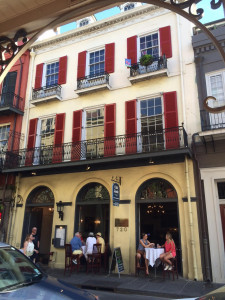

After some legal fuss, Warmoth took over the plantation; the Lawrence townhouse at 68 St. Louis St in New Orleans was sold, and the children seemed to have returned to the North.

68 St. Louis St.

Now 720 St. Louis St., Cafe Soule

Mark Twain visited Magnolia Plantation in 1893 when it was owned by Warmoth. Twain gave no indicated he knew that the plantation had been owned by the brother of Joe Lawrence, for whom Twain had worked in San Francisco in 1863. Twain was fascinated by the machinery.

But even with all the improvements, Louisiana sugar planters could not compete with foreign growers. They tried to get a tariff, but failed. Warmoth sold the plantation, and it gradually deteriorated.

Sic transit