The Quakers have not been immune from factionalism and the split affected the Lawrence family in several ways. It speeded their conversion to Episcopalianism, because the prohibition against marrying out was applied to different branches of Quakers.

| Divisions of the Religious Society of Friends | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wikipedia’s comments seems fair:

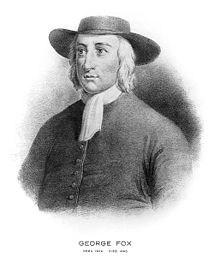

During and after the English Civil War (1642–1651) many dissenting Christian groups emerged, including the Seekers and others. A young man named George Fox was dissatisfied by the teachings of the Church of England and non-conformists. He had a revelation that there is one, even, Christ Jesus, who can speak to thy condition.

Quakers (or Friends, as they refer to themselves) are members of a family of religious movements collectively known as the Religious Society of Friends. The central unifying doctrine of these movements is the priesthood of all believers.

They include those with evangelical, holiness, liberal, and traditional conservative Quaker understandings of Christianity. Unlike many other groups that emerged within Christianity, the Religious Society of Friends has actively tried to avoid creeds and hierarchical structures.

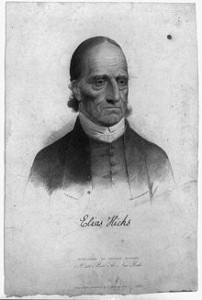

The Hicksite variety influenced the Lawrence family.

Elias Hicks (1748-1830) stressed the role of the Inner Light. “the immediate Communion of the human soul with its Divine Creator and Savior.” as one follower explained it. The Inner Light was equal to or even superior to Scripture:

With the teaching that the Inner Light was on par with the revelation of Jesus from the Bible, Hicksite Quakers removed those boundaries and transformed Quaker religious praxis, distancing it from Bible reading and prayer, and recognizing an ongoing personal reformation through experience in the world. An individual acting in the world could experience Jesus in the same way as someone kneeling in prayer or readng the Bible. Such an understanding tended to minimize the importance of Bible-reading and prayer and sacralized Quaker social action.

Hicks was himself an abolitionist and denounced slavery as the result of war. He wanted to see a boycott of slave-produced goods. This inspired the setting up of stores that sold only products produced by free labor.The first was in Baltimore.

Hicks’s teachings led to a split in the Quakers:

The “great separation” of 1827-28 began in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. Approximately two-thirds of members ranged themselves in the group that came to be called “Hicksite,” and emphasized the role of the Inward Light in guiding individual faith and conscience, while the remaining third, eventually known as “Orthodox,” espoused a more Protestant emphasis on Biblical authority and the atonement. Similar schisms rapidly followed in New York, Baltimore, and elsewhere.

The Lawrences did not go in the direction of social activism. In some of them as we shall see, the Hicksite emphasis on the Inner Light fed into Spiritualism. This influence has continued. Mary Coelho, from her Quaker background and from her studies at Union Theological and Fordham, developed her understanding of the Inner Light:

The adults in our Quaker community spoke often of the Inner Light, the seed of God, the indwelling Christ. “It is a Light within, a dynamic center, a creative Life that presses to birth within us.” The Inner Light might be found in the worshiping community, where it would move a person to speak. The Inner Light might lead a young man to refuse to go to war. It might call someone to alleviate suffering or injustice, and then give them the power to accomplish that task. People testify that through the power of this Light, evil weakens in them and the good is raised up.

For example, a mystical experience at age 29 launched me — rather, hurled and compelled me — into a search that continues to this day. For I had come to know experientially of a powerfully healing and attractive dimension of life not addressed in my science classes. Although not an experience of light, it was an experience of the sacred, and thus closely related to experiences of the Inner Light. I had an inner knowledge, unacceptable as it seems rationally, that what I had known was, in some manner, an answer to humanity’s problems.

I thereby learned to honor the mystical side of Quakerism and to see it as part of a far older tradition that takes as its foundation the experiential side of the religious life. But it was the new story of the evolutionary universe — specifically, the scientific story as translated by Brian Swimme — that enabled me to integrate the manifest, physical world into a dynamic, sacred whole.

It is possible that there are leadings about events not derived from the usual means of communication, although familiarity with a situation through normal means of communication may stimulate an emotional engagement that, in turn, brings forth leadings to address that particular state of affairs. Physicists have, after all, discovered nonlocality, which is action (at the subatomic level) in the absence of local forces. A story told by Jean Shenida Bolen illustrates the kind of nonlocal interconnections in the realm of the individual consciousness that exist in this mysterious world of ours.

As a young child, Jean lived in California with her parents, who were from Japan. On occasion her father would awaken saying that so-and-so back in Japan had died, and that he learned this in a dream. A couple of weeks later, a letter would arrive saying that indeed that person had died at the time her father had known it. How was that knowing, that “leading” possible?

According to M. L. Rowntree, at its best, the Light is the whole self in touch with God and with the universe (quoted in Lucas, p. 16). Such full participation in the universe can bring the individual into leadings that arise outside our local, daily consciousness. The new cosmology gives us confidence that our leadings or callings may go beyond an individual’s isolated ideas, and that a person can be led to actions that do indeed reflect the needs and direction of the larger community and the evolving earth. Likewise, the Quaker idea that refusal of a concern has cosmic consequences finds support in the context of the web of interconnections that is the unfolding whole.

This was the path that Lydia Ann Lawrence (1811-1879), my wife’s third great grandmother, followed.