Effingham Lawrence’s daughter Bessie Amelia was my wife’s first cousin, four times removed. Bessie in 1878 at Magnolia Plantation in Loiusiana married Arthur Coit Gilman (1855-1890).

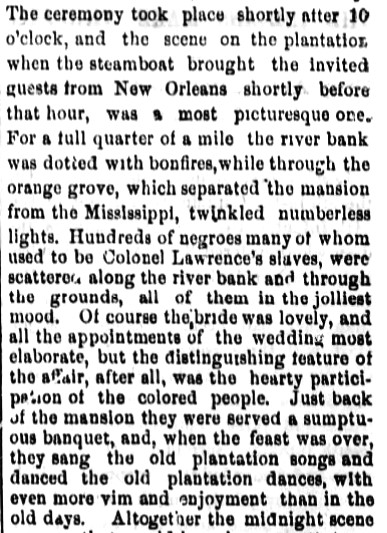

The Independent in Helena, Montana, covered this Christmas Eve wedding:

The Gilmans lived in New York and had three children, Arthur Lawrence (1878-1939), Edward Coit (1879-1909), and Joseph Lawrence (1881-1962). The Gilmans included scientists and Congregational ministers in their background. Arthur Coit Gilman was the nephew of Daniel Coit Gilman (1831-1908), the first president of Johns Hopkins University and co-founder of Gilman School.

Arthur Lawrence, Edward, and Joseph c. 1890

But something went disastrously wrong with Arthur.

Arthur started off as an office boy at the tea firm L. H. Labaree and Co. in March 1879 at $8 a week. He worked his way up to partner, without investing a dollar. He lived very well: he had a house in Flushing (like his Lawrence relatives) and belonged to numerous clubs. He and his wife were among the first box holders at the Metropolitan Opera. Arthur “was an ardent Wagnerian and was active in defense of the composer’s work.”

On December 15, 1890, Arthur said he was not feeling well and would not go to work. He sent a telegram to that effect to the office. His wife and her sister went shopping in town, and he told them he would joint them for lunch at Delmonico’s if he felt better. He then went to his room.

Mr. Labaree received the telegram. He had some business to discuss with Arthur, so he took the train to Flushing. The servant discovered that the bedroom door was locked and was unable to rouse Arthur. They broke the door in, and discovered Arthur, partly clothed, lying on the bed, dead. A physician was called and pronounced that Arthur had died of heart failure.

Several months later it was discovered that he had taken $220,000 ($5,000,000 in 2015 dollars) from the firm, which was consequently near bankruptcy. Independent auditors examined the books and said that

the defalcations had been continuous, deliberate, and intentional, extending from June 1884 to December 1890, and had been conducted with a degree of skill and baseness of treachery which can find but few cases to parallel.

What he did with the money was never known; his income was sufficient to pay for his living expenses. The money he had stolen simply vanished. In the firm’s safe were discovered life insurance policies that Arthur had taken out, naming his wife as beneficiary. They totaled $56,000 ($1,5000,000 in 2015 dollars). The firm claimed these policies on the grounds that the money taken from the firm had paid the premiums. The policies were put in a trust and the matter went to court. Mrs. Gilman maintained that the firm was entitled only to the amount of premiums paid, not to the benefit of the policy. The policies were the only asset left to her. The revelation of the theft and timing of his death also raised suspicions of suicide; but by that time it was too late to do an autopsy.

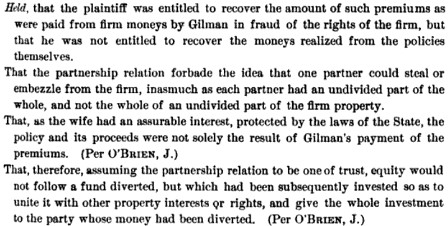

The Supreme Court of New York made this decision:

His widow moved in with her sister, Helen Lawrence, and died in 1937.