Quakers were given that nickname because of their manifestations of movements of the Spirit, much like Pentecostals today. Chief Justice O’Neall (who was descended from Quakers) recounts an event motivated by a charismatic, in the strict sense, preacher. The departure of Quakers from Newberry had a religious cause, in a double sense.

First of all, Quakers developed an antipathy to slavery:

In the beginning, Friends were slave owners in South Carolina. They, however, soon set their face against it, and in their peculiar language, they have uniformly borne their testimony against the institution of slavery, as irreligious. Such of their members as refused to emancipate their slaves, when emancipation was practicable in this State, they disowned.

Note the remark about “when it was practicable.” As in New York, there were restrictions on emancipation, and they increased in the South.

Then a motion of the Spirit led to an exodus.

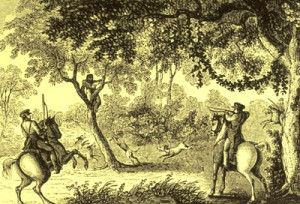

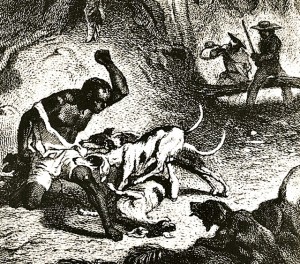

Between 1800 and 1840, a celebrated Quaker preacher, Zachary Dicks, passed through South Carolina. He was thought to have also the gift of prophecy. The massacres of San Domingo were then fresh. He warned friends to come out from slavery. He told them if they did not their fate would be that of the slaughtered Islanders. This produced in a short time a panic, and removals to Ohio commenced, and by 1807 the Quaker settlement had, in a great degree, changed its population.

Newberry thus lost, from a foolish panic and a superstitious fear of an institution [i.e., slavery], which never harmed them or any other body of people, a very valuable portion of its white population.

O’Neall did not include Africans in the category of “people.” Although there was never a general slave revolt, whites lived in constant fear of it, and the events of 1861-1865 were not pleasant for the inhabitants of Newberry. Those who had moved to Ohio were far better off.