Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Parish of the Roman Catholic Personal Ordinariate of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Lent II

February 25, 2018

8:00 AM Said Mass

10:00 AM Sung Mass

____________________________

Hymns

O vision blest of heavenly light

Be Thou my vision

Tis good, Lord, to be here

Anthems

Christus Jesus Splendor, Luca Marenzio (1556-1599)

Ne irascaris, Domine, William Byrd

_______________________________

Hymns

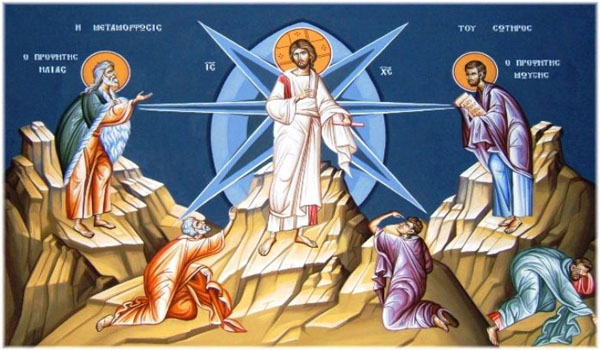

O vision blest of heavenly light

This hymn is a translation by G. B. Timms of a 15th-century Latin hymn, Caelestis formam gloria.

O vision blest of heavenly light,

Which meets the three disciples’ sight,

When on the holy mount they see

Their Lord’s transfigured majesty.More bright than day his raiment shone;

The Father’s voice proclaimed the Son

Belov’d before the worlds were made,

For us in mortal flesh arrayed.And with him there on either hand

Lo, Moses and Elijah stand,

To show how Christ, to those who see,

Fulfils both law and prophecy.O Light from light, by love inclined,

Jesu, redeemer of mankind,

Accept thy people’s prayer and praise

Which on the mount to thee they raise.Be with us, Lord, as we descend

To walk with thee to journey’s end,

That through thy cross we too may rise,

And share thy triumph in the skies.To thee, O Father; Christ, to thee,

Let praise and endless glory be,

With whom the Spirit we adore,

One Lord, one God, for evermore.

This hymn is used for Vespers I on the Feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord in the Sarum Breviary:

Cælestis formam gloriæ,

Quam spes quærit Ecclesiæ,

In monte Christus indicat,

Quo supra solem emicat.Res memoranda sæculis;

Hic cum tribus discipulis

Cum Moyse et Helia

Grata promit eloquia.Assistunt testes gratiæ

Legis atque prophetiæ,

De nube testimonium

Sonat Patris ad Filium.Glorificata facie

Christus declarat hodie,

Quis sit honor credentium

Deo pie fruentium.Visionis mysterium

Corda levat fidelium,

Unde solemni gaudio

Clamat nostra devotio.Pater cum Unigenito

Et Spiritu Paraclito

Unus nobis hanc gloriam

Largire per præsentiam. Amen.

George Boorne Timms ( 1910-1997) was into a Baptist family and was educated at Derby School and St Edmund Hall, Oxford (BA 1933, MA 1945). He joined the Community of the Resurrection, Mirfield, in 1933, and took Holy Orders (deacon 1935, priest 1936). He was curate of St Mary Magdalene, Coventry (1935-38) and of St Bartholomew, Earley, Reading (1938-49); sacrist, and later succentor, of Southwark Cathedral (1949-52); vicar of St Mary the Virgin, Primrose Hill (1952-65) and Rural Dean of Hampstead (1959-65); incumbent of St Andrew, Holborn (1965-81) and Archdeacon of Hackney (1971-81), during part of which time he was also Prebendary of St Paul’s Cathedral (1964-71). In 1981 he retired to Ramsgate; he died in hospital at Margate.

Timms was a well-known liturgist. He also chaired the committees for English Praise (1975) and for the New English Hymnal (1986).

_______________________________________

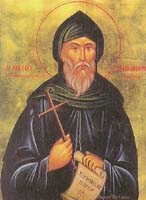

Be Thou my vision

Be thou my vision. The Irish monk Eohaid Forgaill (530-598) was a Latin scholar and “King of the Poets.” He was said to have spent so much time studying that he went blind, and was give the name Dallán, “Little Blind One.” He wrote the poem, “Rop tú mo Baile” (Be Thou my Vision) asking God to be his vision. But “vision” here means more than physical sight. The original Irish word “baile” mean “vision” or “rapture,” in the sense used by the Old Testament prophets. The language of this hymn is drawn from traditional Irish culture: it uses heroic imagery to describe God. This was characteristic of medieval Irish poetry, which cast God as the ‘chieftain’ or ‘High King’ (Ard Ri) who provided protection to his people or clan.

Eohaid Forgaill

The Irish monk Eohaid Forgaill (530-598) was a Latin scholar and “King of the Poets.” He was said to have spent so much time studying that he went blind, and was give the name Dallán, “Little Blind One.” He wrote the poem, “Rop tú mo Baile” (“Be Thou my Vision”) asking God to be his vision But “vision” here means more than physical sight. The original Irish word “baile” mean “vision” or “rapture,” in the sense used by the Old Testament prophets.

This was translated into literal prose by Irish scholar Mary Byrne (1880-1931), a Dublin native, and then published in Eriú, the journal of the School of Irish Learning, in 1905.

Eleanor Hull

Eleanor Hull (1860-1935), born in Manchester, was the founder of the Irish Text Society and president of the Irish Literary Society of London. Hull versified the text and it was published in her Poem Book of the Gael (1912).

Irish liturgy and ritual scholar Helen Phelan, a lecturer at the University of Limerick, points out how the language of this hymn is drawn from traditional Irish culture: “One of the essential characteristics of the text is the use of ‘heroic’ imagery to describe God. This was very typical of medieval Irish poetry, which cast God as the ‘chieftain’ or ‘High King’ (Ard Ri) who provided protection to his people or clan. The lorica (Latin: breastplate) is one of the most popular forms of this kind of protection prayer and is very prevalent in texts of this period.” St. Patrick’s Breastplate (1940 The Hymnal, #268) is in this genre.

Hull’s verse version was paired with the Irish tune SLANE in The Irish Church Hymnal in 1919. The folk melody was taken from a non-liturgical source, Patrick Weston Joyce’s Old Irish Folk Music and Songs: A Collection of 842 Airs and Songs hitherto unpublished (1909).

“Most ‘traditional’ Irish religious songs are non-liturgical,” says Dr. Phelan. “There is a longstanding practice of ‘editorial weddings’ in Irish liturgical music, where traditional tunes were wedded to more liturgically appropriate texts. This is a very good example of this practice.”

Back in 433 AD, on the eve of Bealtine, a Druidic Holiday that lines up directly with Easter as well as the spring equinox, it was declared by the King, Leoghaire (Leary) Mac Neill, that no fires were to be lit until the fire atop of Tara Hill was lit. Going against the kings wishes, St. Patrick went out to Slane Hill and lit a candle to celebrate the resurrection of Christ. The king was so impressed by the courage that St. Patrick had shown, Leoghaire let him continue his missionary work throughout Ireland. The tune was given the name SLANE to commemorate this event.

English translation by Mary Byrne, 1905:

Be thou my vision O Lord of my heart

None other is aught but the King of the seven heavens.Be thou my meditation by day and night.

May it be thou that I behold even in my sleep.Be thou my speech, be thou my understanding.

Be thou with me, be I with theeBe thou my father, be I thy son.

Mayst thou be mine, may I be thine.Be thou my battle-shield, be thou my sword.

Be thou my dignity, be thou my delight.Be thou my shelter, be thou my stronghold.

Mayst thou raise me up to the company of the angels.Be thou every good to my body and soul.

Be thou my kingdom in heaven and on earth.Be thou solely chief love of my heart.

Let there be none other, O high King of Heaven.Till I am able to pass into thy hands,

My treasure, my beloved through the greatness of thy loveBe thou alone my noble and wondrous estate.

I seek not men nor lifeless wealth.Be thou the constant guardian of every possession and every life.

For our corrupt desires are dead at the mere sight of thee.Thy love in my soul and in my heart —

Grant this to me, O King of the seven heavens.O King of the seven heavens grant me this —

Thy love to be in my heart and in my soul.With the King of all, with him after victory won by piety,

May I be in the kingdom of heaven O brightness of the son.Beloved Father, hear, hear my lamentations.

Timely is the cry of woe of this miserable wretch.O heart of my heart, whatever befall me,

O ruler of all, be thou my vision.

Here is the hymnal version. Verse three is usually omitted.

Be Thou my Vision, O Lord of my heart;

Naught be all else to me, save that Thou art;

Thou my best Thought, by day or by night,

Waking or sleeping, Thy presence my light.Be Thou my Wisdom, and Thou my true Word;

I ever with Thee and Thou with me, Lord;

Thou my great Father, I Thy true son;

Thou in me dwelling, and I with Thee one.Be Thou my battle Shield, Sword for the fight;

Be Thou my Dignity, Thou my Delight;

Thou my soul’s Shelter, Thou my high Tow’r:

Raise Thou me heav’nward, O Pow’r of my pow’r.Riches I heed not, nor man’s empty praise,

Thou mine Inheritance, now and always:

Thou and Thou only, first in my heart,

High King of Heaven, my Treasure Thou art.High King of Heaven, my victory won,

May I reach Heaven’s joys, O bright Heav’n’s Sun!

Heart of my own heart, whate’er befall,

Still be my Vision, O Ruler of all.

Although there are hundreds of versions of Be Thou my vision on the Internet, all the vocals ones are not very satisfactory.

Here is the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Here is King’s College, Cambridge.Here it is arranged as an art song. Here sung in Modern Irish. Here is a charming version for violin and harp. A good arrangement for cello and piano. Of course for Celtic instruments. For string quartet. For brass quintet! For marching band!!

_________________________

Tis good, Lord, to be here

‘Tis good Lord to be here was written by Joseph Armitage Robinson (1858-1933), D.D., Dean of Westminster. Jesus, with Peter, James and John, had to come down from the mountain. The next story in Matthew 17 is of Jesus meeting the crowd and healing an epileptic boy; He predicts His death. In the Liturgy, we catch of glimpse of the Uncreated Light that shone through the humanity of Jesus. It is given to strengthen us in the realities and difficulties of everyday life, where God is to be found.

‘’Tis good, Lord, to be here’, but, Lord, when we go, ‘Come with us to the plain’, be with us in the day to day realities of our life, in our relationships with others, in our family or health problems, in all the joys and sadnesses of everyday life.

‘Tis good, Lord, to be here,

thy glory fills the night;

thy face and garments, like the sun,

shine with unborrowed light.‘Tis good, Lord, to be here,

thy beauty to behold,

where Moses and Elijah stand,

thy messengers of old.Fulfiller of the past,

promise of things to be,

we hail thy body glorified,

and our redemption see.Before we taste of death,

we see thy kingdom come;

we fain would hold the vision bright,

and make this hill our home.‘Tis good, Lord, to be here,

yet we may not remain;

but since thou bidst us leave the mount,

come with us to the plain.

Here is a congregation. Here is a most unusual version song perhaps by robots. (For Silicon Valley?)

Joseph Armitage Robinson

Joseph Armitage Robinson (1858-1933), D.D., Dean of Westminster and of Wells, of Christ College, Camb. (B.A. 1881, M.A. 1884, D.D. 1896), sometime Fellow of his College, Norrisian Professor of Div., Camb., Rector of St. Margaret’s., Westminster, and Canon of Westminster. As Dean of Wells Robinson enjoyed close links with Downside Abbey. He also critically explored the origins of the Glastonbury legends. Robinson was a participant in the bilateral Anglican-Roman Catholic Maline Conversations. His hymn, “‘Tis good, Lord, to be here” was written c. 1890. It was included in the 1904 edition of Hymns Ancient & Modern.

The tune SWABIA was composed by Johann M. Spiess (? – 1772). Spiess taught music at the Gymnasium in Heidelberg, Germany, and played the organ at St. Peter’s Church and (1746-72) at Berne Cathedral.

___________________________

Anthems

Christus Jesus Splendor, Luca Marenzio (1556-1599)

Christus Jesus splendor Patris, et figura substantiae ejus, portans omnia verbo virtutis suae purgationem peccatorum faciens, in monte excelso gloriosus apparere dignatus est.

Jesus Christ, radiance of the Father, and the exact representation of his person, upholding all things by the Word of his power, as he was purging our sins, was pleased to manifest his glory upon a high mountain.

Here is the Gregorian version.

Luca Marenzio, (1553—1599) was a composer whose madrigals are considered to be among the finest examples of Italian madrigals of the late 16th century.

Marenzio published a large number of madrigals and villanelles and five books of motets. He developed an individual technique and was skilled in evoking moods and images suggested by the poetic texts of the madrigals. He exploited passages in a homophonic, or chordal, style in place of the polyphonic style characteristic of earlier madrigals. He was a daring harmonist: his chromaticism occasionally led to advanced enharmonic modulations, and he sometimes left dissonances unresolved for dramatic effect. He exerted a strong influence on Claudio Monteverdi, Don Carlo Gesualdo, and Hans Leo Hassler and was much-admired in England, where his works were printed in N. Yonge’s Musica transalpina (1588), a collection that stimulated the composition of English madrigals.

Marenzio was probably trained as a choirboy in Brescia, and he was in service with Cardinal Luigi d’Este in Rome from 1578 to 1586. In 1588 he went to Florence, where he worked with the circle of musicians and poets associated with Count Giovanni Bardi. Later he was in the service of Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini in Rome. In 1594 he visited Sigismund III of Poland, returned to Rome in 1595, and went again to Poland in 1596. In 1598 he was in Venice and later was appointed musician at the papal court.

_______________________

Ne irascaris, Domine, William Byrd

Ne irascaris Domine satis, et ne ultra memineris iniquitatis nostrae. Ecce respice populus tuus omnes nos.

Be not angry, O Lord, and remember our iniquity no more. Behold, we are all your people.

Here is Ely Cathedral. Here is Stile antiquo.

Ne irascaris Domine is a five-part Latin motet by the Catholic English composer, William Byrd (1543-1623). It is one of three works known as the ‘Jerusalem’ motets (along with Tribulations civitatum and Vide Domine afflictionem nostram). Byrd wrote these motets in the 1580s as an act of protest against the Elizabethan Catholic persecutions. As his text, Byrd cunningly chooses here an irreproachable passage of scripture from Isaiah, telling of the Babylonian captivity.

Ne irascaris’ general atmosphere of quiet contemplation coupled with solid polyphonic writing make this a deservedly well known work. Departing from his usual tradition, Byrd sets the appeal to God of Ne irascaris Domine polyphonically, continuing this writing throughout the work. Byrd uses minimal resources (in particular, the melody, which does not move out of the range of a fourth until the end of the work) to create a classic.