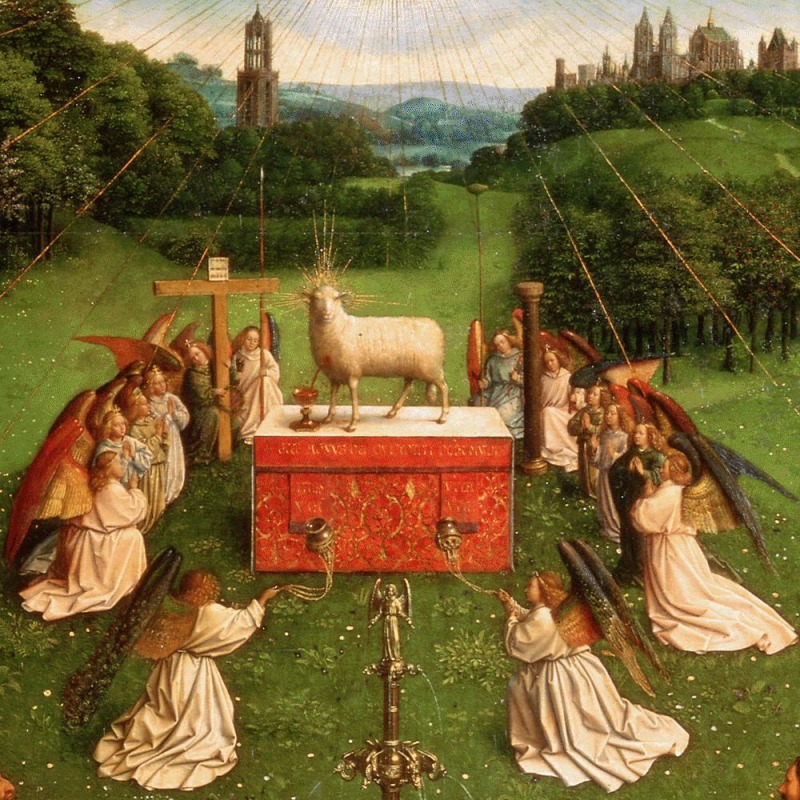

from The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb by Jan van Eyck, 1432

Mount Calvary Church

of the Roman Catholic

Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter

Baltimore, Maryland

July 2, 2017

Hymns

O for a thousand tongues to sing was written by Charles Wesley (17007—1788) on the first anniversary of his conversion. In May 1738, he was suffering severely from pleurisy while he and his brother were studying under the Moravian scholar Peter Boehler in London. At the time, Wesley was plagued by extreme doubts about his faith. Taken to bed with the sickness, on May 21 Wesley was attended by a group of Christians who offered him testimony and basic care, and he was deeply affected by this. He read from his Bible and found himself deeply affected by the words, and at peace with God. Shortly his strength began to return. He wrote of this experience in his journal, and counted it as a renewal of his faith. Charles composed this hymn in 1739. Because of the benefactions that God has made us in creating, redeeming, and sanctifying us, our overwhelming desire should be to praise God in word and deed in gratitude for what He has done to the end that all may know of His great deeds.

And yet, we also sing in the knowledge that the Kingdom of God is not yet fully realized. We proclaim Christ’s victory as a declaration of hope that we will see Christ reign over all. We stand with the voiceless, the lame, the prisoner, and the sorrowing, and lift our song of expectation.

Here is a rousing version at Coral Ridge Presbyterian.

Humbly I adore Thee is a translation and adaptation of part of the Adoro te devote, which was composed by Thomas Aquinas (1225—1274) as a private prayer of devotion. Aquinas addresses Jesus in the sacrament as Truth, “Verity unseen.” For Aquinas, truth was the conforming of the mind to reality. The reality of the Eucharist is that Jesus is present beneath the outward signs of bread and wine. We believe this because Jesus has said it: “This is my Body.” The sacrament is a memorial in the fullest sense of the word: through the Mass the One Sacrifice of Calvary becomes truly present to us. We now see Jesus veiled, but our deepest desire is to see Him face to face. In that vision of God-become-Man for love of us, we are fully conformed to that truth and blessed because we attain the purpose for which we were created.

Here is St. John’s, Detroit.

Now thank we all our God was written by Martin Rinkart (1586—1649) was a minister in the city of Eilenburg during the Thirty Years War. Even apart from battles, lives were lost in great number during this war because illnesses and disease spread quickly throughout impoverished cities. In the Epidemic of 1637, Rinkart officiated at over four thousand funerals, sometimes fifty per day. In the midst of these horrors, it is difficult to imagine maintaining faith and praising God, and yet, that is what Rinkart did. He found the faith to write the hymn, “Now Thank We All Our God,” which was originally meant to be a prayer said before meals. Rinkart could recognize that our God is faithful, and even when the world looks bleak, He is “bounteous” and is full of blessings, if only we look for them. Blessings as seemingly small as a dinner meal, or as large as the end of a brutal war and unnecessary bloodshed are all reasons to lift up our thanks to God, with our hearts, our hands, and our voices.

Here is Nun danket alle Gott, by the Dresdner Kreuzchor. It is at the Semperoper, where I heard the opera that moved me most deeply: Friedenstag.