There were two Eloise Breeses, an aunt and a niece, and they were conflated both by the newspapers and by researches on the internet. I think I have disentangled them.

There were two Eloise Breeses, an aunt and a niece, and they were conflated both by the newspapers and by researches on the internet. I think I have disentangled them.

Eloise Lawrence Breese (1857-1921), usually known as E. L. Breese, was the daughter of Josiah Salisbury Breese (1812-1865) and Augusta Eloise Lawrence (1828-1907). Eloise was the seventh cousin three times removed of my wife.

She had a 9 bedroom house, Nundao, in Tuxedo Park. This

summer cottage in Tuxedo Park faces Tuxedo Lake and is directly across from her brother James Lawrence Breese’s large Tudor Style home that fronted the lake. James was as engineer befriended Stanford White, yet his true passion was photography. It is believed James introduced Eloise to the Architectural firm of Mckim, Mead & White to design her summer cottage in 1889 and Mead and Taft constructed it. The 2 1/2 story cottage has an interesting combination of roof styles, including a Queen Anne Tower.

In Tuxedo Park her French car made on the news in June, 1904. Her chauffeur drove her and five friends around the countryside. They were driving up a hill when a boy, Joseph Mutzs, came over the hill on his bicycle and started making wide swerves. The driver tried to avoid him, but they collided and the boy was killed. The chauffeur took the body to the police. The police chief

told Miss Breese to leave at once, as the friends of the Italian boy might get excited when they heard of the accident and, in spite of the fact that it was the lad’s own fault, make some kind of demonstration. Miss Breese took the advice.

She was known as a bachelorette. She was the only female member of the New York Yacht Club. Her steam yacht, the Elsa, had a swan shaped prow, like the boat in Lohengrin, because Eloise was also a devotee of the opera. She sailed the Elsa to Newport to participate in the July 30, 1901 harbor fete in honor of the North Atlantic squadron. Admiral Higginson’s fleet was assembled in the harbor and a full day of activities—including a exhibition of the submarine torpedo boat Holland—was planned.

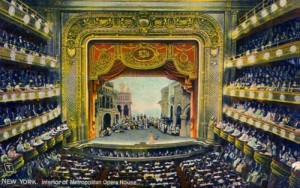

Her box was number 45 at the old Metropolitan Opera.

(I was there once, for a Go0d Friday performance of Parzifal (1966?) with James Ramsey. We had seats with les dieux (it has a ruder name); I could see some of the stage, and could also see the light bulb in the chalice when it was raised. But the music was great.)

Her town house was at 35 East Twenty-Second Street. There she had a long-standing conflict with a neighbor at No 33.

The unmarried Eloise-she preferred that the press referred to her as Miss E. L. Breese-inherited her mother’s unconventional Independence and was a true socialite that entertained lavishly, often arranging concerts in her Tuxedo Park ballroom. Her fashions of the time were also rather scandalous as she preferred off the shoulder evening gowns with plunging necklines, the french fashion was shocking to most Victorian minds.

Mrs. Elizabeth B. Grannis, a self-appointed combatant against sin. Mrs. Grannis was president of the Woman’s Social Purity League as well as president of the National League for the Protection of Purity. In December 1894 her search for sin would place her squarely in the social territory of Eloise Breese.

The Evening World reported on December 1, 1894 that Mrs. Grannis lately “has been engaged in seeing for herself just how wicked New York really is.” Having visited (escorted by her brother, Dr. Bartlett) “nearly all the dance and concert halls, theatres, joints, missions and dives in this city,” she turned her focus to the Metropolitan Opera and its wealthy patrons.

Mrs. Grannis took an Evening World reporter in tow and explained the Purity League’s plans to abolish the décolleté dress. “What we want to do is to call public attention to the evil, and by this means to shame people into dressing differently.” She admitted,when the reporter said that judging from the Metropolitan audience “Mrs. Grannis’s idea cannot be said to have borne much fruit,” that it would take time. She blamed the absence of social purity on two forces. “One reason is the décolleté dress; the other and greater is the round dance.”

Mrs. Grannis approved of “a modest square dance like the lanciers or the minuet,” but waltzing “and every other form of round dance is, per se, sinful.”

The equally strong-minded Eloise Breese disagreed. And the two women would make their differences known repeatedly. While the social reformer railed against the high fashion of the young socialite and her wealthy friends, Eloise frequently complained to authorities about “smells” coming from the Grannis home.

In 1902 Eloise L. Breese had had enough of her pious next-door neighbor and she purchased the Grannis house “with the understanding that it was to be pulled down,” said The Sun. But she had second thoughts and once the social reformer had moved out “the temple of social reform and universal peace has been turned into a boarding house,” reported the newspaper later.

The rooms where Mrs. Grannis had held meetings of other virtuous women and church leaders were now decorated by Eloise “in the highest form of boarding-house art with bows and arrows of primitive peoples and the heads of savages in war paint.”

But she wasn’t done yet.

In May 1903 Eloise sued Elizabeth Grannis for $249 saying that “when she moved out, [she] took with her a bathtub and the chandeliers.”

Mrs. Grannis appeared baffled and unruffled. “How silly,” she told reporters. “Think of going to court for just one little bathtub. It is my personal, individual tub. Of course I took it with me. I told them I was going to, but offered to sell it to them with the chandeliers.”

The reformer complained that the Breese family had always been a problem. “What a flibberty-gibberty commotion it is. I lived beside the Breeses eighteen years and never met them, but they were forever sending in to complain of smells they thought they smelled and to see if there wasn’t a fire or a leak or something in my house.”

The town house does not survive, but the carriage house that Eloise built exists in a glorified state.

150 East 22nd Street

She married late, in 1907 when she was fifty, to Adam Gorman Norrie, a widower.

Her nephew, William Lawrence Breese, had become a naturalized British subject and died in battle in 1915. She gave an ambulance in his memory.

She made an important bequest to the Metropolitan Museum:

Upon her death on January 28, 1921 she added significantly to the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art by bequeathing two important paintings, one by Rousseau and another by Corot (his “The Wheelwright’s Yard on the Bank of the Seine”). Even more importantly, she left the museum the incomparable 17th century Audenarde tapestries representing the history of the Sabines.

The Wheelwright’s Yard on the Bank of the Seine