The second child of Clifton Stevenson Brown and Katherine Boyce Tupper was Clifton Stevenson Brown, Jr. (1914-1952). He was the third cousin once removed of my wife.

During the war Colonel Brown served in Africa, Sicily, Italy, France and Germany. He and his brother Allen were only seven miles apart in Italy. While he was in the Army of Occupation in Germany an old radium burn on his foot flared up and he was evacuated to Walter Reed, but was released and was able to go through with the wedding. He married Em Bowles Locker on August 25, 1945 at St. Stephen’s Church in Richmond, H. St. George Tucker, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, conducted the ceremony; Kermit Roosevelt was a guest. He and Em had one child, Carter Boardman (1949- )

After the war he worked for Louis Marx Company, the toy manufacturer, and for IBM. He died in Walter Reed Hospital at the age of thirty-eight.

Em Bowles Locker

Em Bowles Locker (1916-2015) was a native of Richmond with a perfect Southern accent.

Her chance for undying fame came when she tried out for the role of Scarlett O’Hare.

Em Bowles first learned of Margaret Mitchell’s seminal Civil War-era novel in August 1936 on her way home from Camp Michigamme in Michigan, where she had spent the summer working as a sailing and drama instructor.

During a stopover at Vassar-friend Mary Morley Crapo’s house north of Detroit, Em Bowles noticed a book opened and turned upside down sitting next to the fireplace. It was “Gone With the Wind,” and Mary was convinced that Em Bowles would make the perfect Scarlett in the movie, which was already in the works.

Once home in Richmond, Em Bowles picked up her mother’s new copy of the novel.

“I took it back to Vassar with me and almost flunked out the first month because I was reading it!” she says.

The girls unanimously urged their Richmond friend to try out for the part — though Em Bowles was not just another pretty face with genteel Southern manners. She was a seasoned amateur actress who had already spent three years acting with Vassar’s well-known Experimental Theater.

She had a full dress screen test, but she was deliberately given bad advice by someone who favored a different candidate, and lost out.

Frank McCarthy and Em Locker 1937

However, she did get to attend the premiere in Richmond.

At the “Gone With the Wind” premiere in Richmond the following month, she led a procession from Capitol Square to Loew’s Theater and spoke to the audience about the film and her special part in bringing it to life.

Later, at a special celebration of the film at the John Marshall Hotel, she and childhood friend Frank McCarthy — a Virginia Military Institute graduate who would go on to serve as a wartime aide to Gen. George Marshall, assistant secretary of state and become a producer for the motion picture “Patton” — led the Grand March and Exhibition Waltz.

That was the end of her acting career.

Em Locker, 1942

It was presumably through McCarthy that she met Gen. Marshall’s stepson, Clifton Brown. McCarthy was the best man at the wedding, and Molly was the maid of honor.

Em Locker, 1945

Her obituary details her work in public relations.

ALSOP, Em Bowles Locker, who was known at national, state and local levels as a public relations innovator and accomplished civic leader, passed away on March 3, 2015, at the age of 98. Born in Richmond on November 16, 1916 to noted educator Willis Clyde Locker of Orange, Va. and Mary Augusta Bowles (a 1905 Hollins graduate) of Salem, Va., she was predeceased by her brother, Corporal Willis Clyde Locker Jr., decorated for bravery and killed in action in World War II; and by her husband of 46 years, Benjamin Pollard Alsop Jr. She is survived by her daughter, Carter Alsop. After St. Catherine’s School in Richmond, Mrs. Alsop went to Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, N.Y. where, fluent in both French and German, she was chosen to spend a summer at the University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany during Hitler’s pre-war reign. Upon graduation from Vassar in 1937, she was appointed by the president of the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Va. to serve as assistant to the Director of Public Relations. In this capacity, she researched historic Williamsburg’s first Guide Book. Soon, she moved to New York City where, having become a model with the Powers Modeling Agency, she was chosen by its founder, John Robert Powers, to develop – and to become – the first director of a modeling school that would expand the services of his agency. Originally named Powers School, it is currently called John Robert Powers New York. As director, she was a sought-after public speaker, a radio show guest, a journalist for national media and a public relations consultant for Eastern Airlines, Coty Perfume, Revlon lipstick, The Rheingold Brewing Company and Columbia University. For the Rheingold company, she created a new marketing concept. She chose a professional model as a corporate symbol to be “Miss Rheingold”. This set in motion the employment of beautiful women trained as spokesmodels to grace advertising and marketing campaigns throughout corporate America. Returning to Richmond during WWII, she envisioned an event – “The Book and Author Dinner” – for Miller & Rhoads Department Store to drive sales and boost store brand recognition. She was later cited as the event’s Founder by The Junior League of Richmond. Working also for the USO, the War Bond Drive and the Aircraft Recognition Center, she went on to become a noted fundraiser for several nationally recognized war benefit programs in New York and Washington, D.C. After the war, while living again in New York, she was asked by Helen Hayes “Queen of the American Theater,” if she would become her Executive Assistant. This began a lifelong friendship between the two. In 1953, three years after returning – once again – to Richmond, she married Mr. Alsop. October, 1954: her national promotion of the first Autumn Tour of Virginia’s Historic Sites drew thousands of visitors to Virginia for the one day event in spite of the arrival of Hurricane Hazel! 1955.

For some reason the obituary does not mention the first marriage.

She lived to be almost 100; but she said a lady never reveals her birthday.

Em Locker at ?

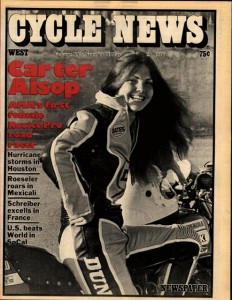

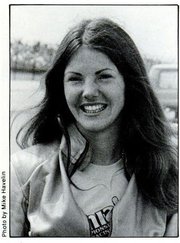

Carter Boardman (Brown) Alsop

Carter Boardman Brown (1949), who took the name of her mother’s second husband, Benjamin Pollard Alsop, Jr., is my wife’s fourth cousin. Carter was born in 1949, and indicates her parents’ marriage ended in divorce when she was an infant.

She is a debutante and motorcyclist:

In 1977 she became the first woman to be granted a professional road-racing license by the American Motorcyclist Association. The following year she won her first major championship, the Western-Eastern Roadracers’ semipro series, placing first in eight of 16 national events. Though she spent much of last season out with injuries, Alsop hopes to compete this March in the Daytona 200, the Kentucky Derby of motorcycle competition. She will not be the first woman to start in the race, however; Gina Bovaird entered but did not finish last year. Carter thinks she has a good chance to complete the grueling run. “It’s like Rocky, ” she says with a smile. “I just want to go the distance.”

As a teenager she exhibited her landscapes in a Richmond art gallery and fought with her mother and stepfather, a retired manufacturer, over coming out as a debutante. They won. Carter was introduced to society at parties in Manhattan, Philadelphia and Richmond. She claims she only went along “to enjoy the dancing.” At 20, she quit Briarcliff College to take up motorcycle racing. Her parents were aghast. Carter had seen a classmate with a helmet covered with racing stickers. “It belonged to her fiancé,” Carter says. “From that moment I knew I wanted to race bikes. I’d always wanted a motorcycle. I’d grown up on horses. It was an extension of a horse.”

To support herself, Carter painted murals and portraits, sold vacuum cleaners and started a furniture business. Then, in 1974, she went to work for a Honda dealer in Richmond. “They had a prize for the best salesman of the week—one hour at the local massage parlor,” she laughs. “I won it every week.”

In 1975 she returned to Briarcliff, graduating two years later with a bachelor’s degree in English literature and art. She turned down a chance to apply for a Rhodes scholarship and returned to the race track. “I was alone,” she says. “I slept in the back of an open truck next to the spare parts. I even had to hitchhike to one meet. It was lonely.”

Though she won the 1979 national sidecar championship race with driver Wayne Lougee, the season proved disastrous for Carter. She lacked a sponsor (a season on the circuit can cost $100,000) and was sidelined constantly by equipment failures and accidents. She has suffered three concussions, broken her collarbone four times and aggravated a chronic back problem. “My neurologist said I wasn’t in any immediate danger,” she reports, “but he told me a time will come when the head injuries could cause problems.”

When her racing career ends, Alsop will have no problem finding other outlets. She has already appeared as a stunt woman in the Burt Reynolds movie Hooper, is rewriting a screenplay about a female motorcycle racer for a Hollywood producer and would like a career in broadcasting—”or perhaps be the first woman to break the speed of sound on land. I’ll always compete,” she says. “It’s in my blood.”

In the Reynolds movie she crashed into a “brick” wall. She explained:

It actually was a balsa wood “wall” with cartons and mattresses on the other side, but it was dangerous, as were some of the other jobs I did as a stunt woman. The pay was very good – and it was nice to be paid for crashing for a change.

She seems to have survived her career.

Carter Alsop