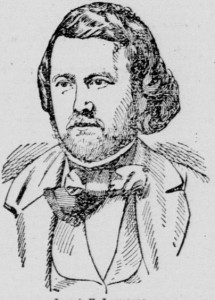

Joseph Effingham Lawrence, age 18

Bayside, Queens

Joseph Effingham Lawrence (1824-1878) was the son of Effingham Lawrence and Anne Townsend, and therefore the third great grand uncle of my wife. He was the brother of Lydia Lawrence, noted for her tendencies to marry her cousins and for her interest in Spiritualism, of Effingham Lawrence, owner of Magnolia Plantation in Louisiana and of Henry Effingham Lawrence, wealthy merchant in New Orleans and father of six children, four of whom were born deaf and were therefore important in the history of the education of the deaf in the Old South

Joseph was in Louisiana, presumably visiting his brother, when the news of the 1849 Gold Rush reached him. At the age of twenty five he made his way across Texas and Mexico by mule, and settled in California. He decided to become an editor. In California the Effingham became a simple E., and he preferred to be known as Joe Lawrence. The only place where his full name is listed in in the role of graduates of Columbia University (class of 1841).

However, when he was editor of the Sacramento Placer Times, he acquired the title of Colonel. Governor John Bigler of California appointed him aide to Camp with the title of Colonel of Calvary, with the notice “place him where France most needs a soldier.”

This provoked the comment

This is the manner by which the United States acquires so many colonels; the governor of each state can appoint himelf four aides-de-camp; from the date of appointment they rank with the title “colonel of the Calvary”; they are not selected from military life; the qualifications of the new colonel editor are set forth in the notice; but I think the line should read “place him here France least wants a soldier,” if these are the only titles to a soldiers name.

The Hazards of Being an Editor

Joe Lawrence was editor of the Sacramento Placer Times (later the Times and Transcript) from 1850 to 1854. An editor’s life was not an easy one.

Joe Lawrence was editor of the Sacramento Placer Times (later the Times and Transcript) from 1850 to 1854. An editor’s life was not an easy one.

In July 1851 Joseph nearly cut short the career and life of the future governor of California, Neely Johnson.

As Mr. Lawrence was passing the court-house, J. Neely Johnson stepped up and demanded to know whether he was the author of a certain paragraph published in the Times and Transcript that morning, at which Johnson had taken offence. Not receiving a satisfactory reply, Johnson seized the journalist’s nose and wrung it magisterially. Lawrence drew a pistol and would have fired had he not been disarmed by the by-standers.

In October 1851 Joseph wrote to the Sacramento City Council:

Gentlemen: On Friday afternoon, passing along the Levee, between K and L streets, I was addressed in an extremely abusive manner by several members of the Chain Gang, engaged in repairing the embankment at that place. – One of them stepped near men, and with violent gestures threatened a personal assault, continuing also to use the most scurrilous expressions. The person seeming in charge of the gang, whose name I have understood to be Keithly, made no effort to quell the disturbance, and only requested the leader in it to desist from an attack, himself uttering at the same time language little, if any less abusive than that of his confederates in this outrage, which he justified on account of a publication that had appeared in the Placer Times and Transcript, regarding the Station House.

In 1858 a William Grey was sentenced to pay a fine of $25 for his assault and battery on Joseph Lawrence.

Lawrence decided become involved in more literary endeavors.

The Golden Era

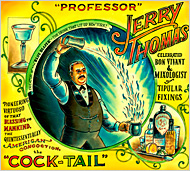

Masthead of the Golden Era

The Golden Era was founded in 1852 by Rollin M. Daggett and J. McDonough Ford. They aimed at the new population of God Rush California and sought to present

a Good Family newspaper. Calculated for circulation in every parlor and miners’ cabin that would be of interest to the merchant, the farmer and the mechanic. Untainted with politics and unbiased by religious prejudice.”

It contained everything form recipes for baked beans to and notices such as “James E Rogers, blew his brains out, September 2nd. Cause: Discouraged,” to serialized stories. The Golden Era would specialize in Western literature,

the incidents and characters of the mining camps, the novelty and peculiarity of which sufficed to impart a special stamp to the narration

The newspaper would therefore concentrate on native writers:

we do contend that foreign writers should not be brought into daily, weekly, or monthly contact with the people…to the exclusion of native writers. We contend further that in order to secure a hearty literature, ‘racy of the soil,’ these native writers should receive all possible encouragement.’

Its rural readers looked forward to each edition of the Golden Era:

Many times the Era has gladdened my heart amid the rude mountains of the Sierra, when the whoop of the Digger-Indian, the growl of the fierce grizzly, or the screams of our emblem bird, the Eagle, were more frequent and familiar sounds than those of church bells.

Joe Lawrence began his association with the Golden Era in 1854. It was reported that

The Golden Era of Sunday says ” What I Saw in Oregon,” is to be the title of a work now undergoing publication in this city, from the pen of J. E. Lawrence, Esq. It will be remembered that this gentleman lately made a short but thorough tour of that territory, and report say* that the work will comprise principally the impressions of the author, formed by the combined operation of the five senses upon sensitive imagination in cloudy weather. We look for it with anxiety.

In 1860 he and James Brooks purchased the newspaper and Lawrence became its editor. He had an eye for literary talent. He deemphasized local color for more serialized stories and social satire. Under his aegis the Golden Era combined

European intellectualism and Pacific Coast empiricism…to create one of history’s most exciting intellectual atmospheres

And continued to

penetrate the wilderness as persistently as canned oysters.

Joe Lawrence was well-liked:

the very pattern of paternal patronage was amiable Joe Lawrence , its Editor.” He was an inveterate pipe-smoker, a pillar of cloud, as he sat in his editorial chair, an air of literary mystery enveloping him.

The Golden Era had a column in which it published amateur poetry. It had some standards, although the standards were low:

An enthusiast for Burns who had sent in a Scotch ballad entitled To a Flea was advised: “The first stanza is very Scotch, the next is slightly Scotch, the next is Scotchless, and all the rest are nix Scotch. It is a pity you did not imbibe more Burns before you burst.” Duly Scotched, the poem was returned and printed. Just as bad were the verses in Chinook contributed by an Oregonian, and the trifle on a humming-bird and bumble-bee which ran:

The humming bird and bumble bee

One Summer’s day got on a spree;They guzzled together with floral licker

Till they got sicker, and sicker, and sicker.The bird pecked at the bumble’s thighs

The bumble whacked her in the eyes;And then they fit and fit and fit,

Until they couldn’t get up and git.

The advertisements are fascinating for the modern reader:

They range from current theater programs and maritime notices of clipper ships, with all the romance evoked by the names of Lola Montez or the Flying Cloud, to advertisements for New Codfish, Balsam for the Lungs,Extract of Sarsaparilla and Stillingia, or the omnipresent Squarza’s Punch. In one column thevirtues of patent overspring pianofortes were extolled, while in another the makers of Lyon’s FleaPowder took advantage of the miner’s passion for rhyme:

In summer when the sun is low,

Come forth in swarms the insect foe,

And for our blood they bore, you know,

And suck it in most rapidly.

. . .But fleas, roaches, ‘skeeters — black or white —

In death’s embrace are stiffened quite,

If Lyon’s powder chance to light

In their obscure vicinity.

The Golden Era was the product of the milieu that Mark Twain describes in Roughing It: overwhelmingly male, very young, violent, adventurous, skeptical, irreverent, coarse. This milieu set its mark on American literature.

Artemus Ward (1834-1867)

Artemus Ward (Charles Ferrar Brown) was America’s first stand-up comedian.

In 1858, Brown created the persona of Artemus Ward, a poorly educated traveling showman with a wealth of puns and misspellings. Ward’s instinct for folk humor presented with malapropisms made him nationally popular. He was the favorite comic of President Abraham Lincoln, who often read Ward to begin cabinet meetings.

The persona of Artemus Ward and the young Abraham Lincoln

Nineteenth-century convention allowed other newspapers to reprint Ward’s columns without compensation. Brown subsequently took his show on the road, lecturing and selling books of his reprinted articles. Initially, Brown’s appearance—tall, thin, and young—astounded audiences who expected the short, rotund, middle-aged Ward depicted in lithographs. Nevertheless, Brown’s wit and onstage charisma created diehard fans as he presented his farcical speech, “The Babes in the Wood.”

The Englishman Edward Higsston was the advance man in San Francisco for Artemus Ward (born Charles Ferrar Brown), who in 1863 was to give his lecture-entertainment, Babes in the Woods.” Joe Lawrence liked what he read by Ward and decided the lecture needed a special advance notice. Hingston remembers:

Magnanimous was the behavior of Colonel Lawrence of the Golden Era , who begged to be supplied with any amount of copy, and with enthusiastic liberality declared that he would make the forthcoming number of his paper an Artemus Ward number. He was duly furnished with biographical notes, critical essays, and sample of the humor of the new humorist. But not satisfied with the quantity of matter with which he was already stocked, he “took a drink,: and then blandly said, “Can’t you let me have an article about him in connection with Shakespeare and Spiritualism.” [This perhaps indicates Joseph’s attitude to the Spiritualism espoused by his sisters Hannah and Lydia.]

To confess inability to a Californian would have been absurd. Colonel Lawrence was therefore informed that he could have such an article if he particularly wished for it, though how Artemus Ward was to be connected with either, did not strike the mind as questions being easy of solution. Spiritualism was a prominent topic in San Francisco just then. Hence it admitted of being used to advantage, but why Shakespeare? The Colonel pointed out a ready made mode of making up an article. “Get Mrs. Mary C. Clarke’s Dictionary,” said he “and see what you can find about ‘Ward’ in it,”

Thanking the Colonel for the idea, I suggested that I might find difficulty in obtaining Mrs. Cowden Clarke’s ‘Concordance to Shakespeare in a San Francisco library.

“Guess we’ve got her upstairs,” was the reply. “Mary C. Clarke, Webster, and Lippincott are kinder useful tools in an office.”

Hingston produced this article for the Golden Era:

Shakespeare an agent for Artemus Ward – A Strangely New Phase of Spiritualism. – Spiritualism has originated many new and startling ideas. The mental vagaries of some of its professors outstrip the wildest conceptions of the most imaginative poets. The latest theory propounded is, however, by far the most surprising; while the proofs adduces are of the most extraordinary description

We will give the theory in a few words. Incorporate mortals now existent, can not only hold communication with decorporated spirits, but the spirits of all who are to wear fleshly garb can also hold present intercourse with other spirits who have yet to be incarnated.

This theory is based on the doctrine propounded by the Rev. Charles Beecher, for which he was recently denounced by the convention of ministers at Georgetown, D.C. It is the doctrine of pre-existence; – that our spirits have lived from all time as they are to live to all time. That the soul of John Smith lived long ages ago, as it will live in the immeasurable ages to come. Herein arose the opportunity for Belshazzar of Babylon to know about the soul of John Smith whom we meet on Montgomery Street to-day. This is the strange new theory.

It is proven by the fact that Shakespeare knew Artemus Ward three hundred years ago, and acted then as “agent in advance” of Artemus, by advertising him to the full extent of his ability. Now Shakespeare must have known that the spirit of Artemus, when fleshified as Ward, would produce a good fellow, or he would not have done it. For Shakespeare himself was a good fellow, and ought to have owned as many feet in the “Gould and Curry” as the best of us.

Here are the facts, startling as we admit; but as undeniable as any fact ever yet adduced in support of a theory:

Shakespeare’s acquaintance with Artemus was of long standing. “thou knowest my old Ward,” says he. (I Henry IV., act iv.) That he esteemed him highly is manifest, for he calls him “the best Ward of mine honour.” (Love’s Labor Lost, act iii, scene i.) That he advises everyone to hear him and to know him is plain, for says he not, “Come mot my Ward. “ (Measure for Measure, act iv., scene iii.) That he himself had diligently to attend to the matter of Artemus is certain, for his own words are, “they will have me go to Ward. ( 2 Henry vi, act v, scene i.) Sometimes Shakespeare appears to have been persuaded a little too strongly by Artemus, for his words are, “I cannot Ward, what I would not.“ (Troilus and Cressida, act i, scene ii); and again – wary fellow – “There are many confines, Ward. (Hamlet, act ii, scene i.) Strangely prescient of the future fact that Mr. Browne would achieve fame about twenty-four months after adopting his nom-de-plume, he says of Artemus’ father, “His son was but a Ward two years.” (Romeo and Juliet, act i., scene v.) That he thought him to be smart, and to know as much as half a dozen men, is evidenced by his assertion that there are “men in your Ward.” (Measure for Measure, act ii., scene ii.) And, that he believed him to be guileless is demonstrable, or he would never have called him “The Ward of purity.” (Merry Wives, act iv, scene iii.) Just as he know him to be shrewd when he entitles him “The Ward of covert, (Measure for Measure, act v, scene i.) How plainly evident too it is, that the spirit of Artemus used to call upon Shakespeare (whether by raps on the table or at the door we know not,) for does not the poet answer him and say, “I am now in Ward.” (All’s Well that Ends Well, act I, scene ii.) Ward’s spirit, however, was not always truthful to Shakespeare; the principal did not treat the agent candidly, for Shakespeare says,“Ward, you lie.” (Troilus and Cressida, act I, scene ii.) And shortly afterwards “all these Wards lie.” Possibly, however, Shakespeare was irritated at the time, and Artemus may have sent him a message by telegraph, which was slightly spoiled by the operator.

The above facts prove, however, that Shakespeare knew the great humorist of America in Spirit; that where he has a chance of saying anything for him he did it; that he never lost a chance of mentioning his name, and was always an industrious agent. It now remains for Artemus to do his part; and, having become incorporate, to look about him in San Francisco, and do the handsome in return for his spirit friend.” – E. P. H.

The lecture was a success.

Mark Twain (1835-1910)

As a boxer – one of Twain’s favorite photographs of himself

Samuel Longhorn Clemens was a newspaper man in Virginia City, Nevada, when he began submitting articles to the Golden Era. They caught the eye of Artemus Ward, who sought out Clemens when he visited Virginia City in 1863 and encouraged him in his writing.

near the end of May, 1864, when Mark Twain left Nevada for San Francisco. The immediate cause of his going was a duel–a duel elaborately arranged between Mark Twain and the editor of a rival paper, but never fought. In fact, it was mainly a burlesque affair throughout, chiefly concocted by that inveterate joker, Steve Gillis, already mentioned in connection with the pipe incident. The new dueling law, however, did not distinguish between real and mock affrays, and the prospect of being served with a summons made a good excuse for Clemens and Gillis to go to San Francisco, which had long attracted them.

The twenty-eight-year-old Clemens had adopted the name Mark Twain only month before he arrived in San Francisco in May 1864. Lawrence offered him $5 an article, and Twain began producing at least thirty-nine articles for the Golden Era.

Newspapers at the time described the dress of female participants in social events in excruciating detail. I have transcribed some of them in the blogs on Lawrence and Alexandre weddings. Twain took on the talk of describing the dress at the Lick Hotel Ball.

Mrs. F. F. L. wore a superb toilette habillee of Chambery gauze; over this a charming Figaro jacket, made of mohair, or horse-hair, or something of that kind; over this again, a Raphael blouse of cheveux de la reine, trimmed round the bottom with lozenges formed of insertions, and around the top with bronchial troches; nothing could be more graceful than the contrast between the lozenges and the troches; over the blouse she wore a robe de chambre of regal magnificence, made of Faille silk and ornamented with maccaroon (usually spelled “maccaroni,”) buttons set in black guipre. On the roof of her bonnet was a menagerie of rare and beautiful bugs and reptiles, and under the eaves thereof a counterfeit of the “early bird” whose specialty it hath been to work destruction upon such things since time began. To say that Mrs. L. was never more elaborately dressed in her life, would be to express an opinion within the range of possibility, at least – to say that she did or could look otherwise than charming, would be a deliberate departure from the truth.

Mrs. Wm. M. S. wore a gorgeous dress of silk bias, trimmed with tufts of ponceau feathers in the Frondeur style; elbowed sleeves made of chicories; plaited Swiss habit – shirt, composed of Valenciennes, a la vieille, embellished with a delicate nansook insertion scolloped at the edge; Lonjumeau jacket of maize-colored Geralda, set off with bagnettes, bayonets, clarinets, and one thing or other -beautiful. Rice-straw bonnet of Mechlin tulle, trimmed with devices cut out of sole-leather, representing aigrettes and arastras – or asters, whichever it is. Leather ornaments are becoming very fashionable in high society. I am told the Empress Eugenie dresses in buckskin now, altogether; so does Her Majesty the Queen of the Shoshones. It will be seen at a glance that Mrs. S.’s costume upon this occasion was peculiarly suited to the serene dignity of her bearing.

Mrs. A. W. B. was arrayed in a sorrel organdy, trimmed with fustians and figaros, and canzou fichus, so disposed as to give a splendid effect without disturbing the general harmony of the dress. The body of the robe was of zero velvet, goffered, with a square pelerine of solferino poil de chevre amidships. The fan used by Mrs. B. was of real palm-leaf and cost four thousand dollars – the handle alone cost six bits. Her head dress was composed of a graceful cataract of white Chantilly lace, surmounted by a few artificial worms, and butterflies and things, and a tasteful tarantula done in jet. It is impossible to conceive of anything more enchanting than this toilet – or the lady who wore it, either, for that matter.

Mrs. J. B. W. was dressed in a rich white satin, with a body composed of a gorgeously figured Mackinaw blanket, with five rows of ornamental brass buttons down the back. The dress was looped up at the side with several bows of No. 3 ribbon – yellow – displaying a skirt of cream-colored Valenciennes crocheted with pink cruel. The coiffure was simply a tall cone of brilliant field-flowers, upon the summit of which stood a glittering ‘golden beetle’ – or, as we call him at home, a “straddle-bug.” All who saw the beautiful Mrs. W. upon this occasion will agree that there was nothing wanting about her dress to make it attract attention in any community.

Mrs. F. was attired in an elegant Irish foulard of figured aqua marine, or aqua fortis, or something of that kind with thirty-two perpendicular rows of tulle puffings formed of black zero velvets (Fahrenheit.) Over this she wore a rich balmoral skirt – Pekin stripe – looped up at the sides with clusters of field flowers, showing the handsome dress beneath. She also wore a white Figaro postillion pea-jacket, ornamented with a profusion of Gabriel bows of crimson silk. From her head depended tasteful garlands of fresh radishes. It being natural to look charming upon all occasions, she did so upon this, of course.

Miss B. wore an elegant goffered flounce, trimmed with a grenadine of bouillonnee, with a crinoline waistcoat to match; pardessus open behind, embroidered with paramattas of passementerie, and further ornamented at the shoulders with epaulettes of wheat-ears and string-beans; tule hat, embellished with blue-bells, hare-bells, hash-bells, etc., with a frontispiece formed of a single magnificent cauliflower imbedded in mashed potatoes. Thus attired Miss B. looked good enough to eat. I admit that the expression is not very refined, but when a man is hungry the similes he uses are apt to he suggested by his stomach.

Twain may have heard about Joe’s sisters Hannah and Lydia, and perhaps met Hannah on one her visits West. In any case Twain knew of the interest among Spiritualists in rappings:

There was an audience of about 400 ladies and gentlemen present, and plenty of newspaper people — neuters. I saw a good-looking, earnest-faced, pale-red-haired, neatly dressed, young woman standing on a little stage behind a small deal table with slender legs and no drawers — the table, understand me; I am writing in a hurry, but I do not desire to confound my description of the table with my description of the lady. The lady was Mrs. Foye.

As I was coming up town with the Examiner reporter, in the early part of the evening, he said he had seen a gambler named Gus Graham shot down in a town in Illinois years ago, by a mob, and as probably he was the only person in San Francisco who knew of the circumstance, he thought he would “give the spirits Graham to chaw on awhile.” (N. B. This young creature is a Democrat, and speaks with the native strength and inelegance of his tribe.) In the course of the show he wrote his old pal’s name on a slip of paper and folded it up tightly and put it in a hat which was passed around, and which already had about five hundred similar documents in it. The pile was dumped on the table and the medium began to take them up one by one and lay them aside, asking “Is this spirit present? — or this? — or this?” About one in fifty would rap, and the person who sent up the name would rise in his place and question the defunct. At last a spirit seized the medium’s hand and wrote “Gus Graham” backwards. Then the medium went skirmishing through the papers for the corresponding name. And that old sport knew his card by the back. When the medium came to it, after picking up fifty others, he rapped! A committee-man unfolded the paper and it was the right one. I sent for it and got it. It was all right. However, I suppose “all them Democrats” are on sociable terms with the devil. The young man got up and asked:

“Did you die in ’51? — ’52? — ’53? — ’54? –”

Ghost-” Rap, rap, rap.”

“Did you die of cholera ? — diarrhea ? — dysentery ? — dog-bite? — small-pox? — violent death? –”

“Rap, rap, rap.”

“Were you hanged? — drowned? — stabbed? — shot?”

” Rap, rap, rap. ”

” Did you die in Mississippi? — Kentucky? — New York? — Sandwich Islands? — Texas? — Illinois? –”

” Rap, rap, rap.”

“In Adams county? — Madison? — Randolph? –”

“Rap, rap, rap.”

It was no use trying to catch the departed gambler. He knew his hand and played it like a Major.

I was surprised. I had a very dear friend, who, I had heard, had gone to the spirit land, or perdition, or some of those places, and I desired to know something concerning him. There was something so awful, though, about talking with living, sinful lips to the ghostly dead, that I could hardly bring myself to rise and speak. But at last I got tremblingly up and said with low and reverent voice:

“Is the spirit of John Smith present?”

“Whack! whack! whack! ”

God bless me. I believe all the dead and damned John Smiths between hell and San Francisco tackled that poor little table at once! I was considerably set back — stunned, I may say. The audience urged me to go on, however, and I said:

“What did you die of?”

The Smiths answered to every disease and casualty that man can die of.

“Where did you die! ”

They answered yes to every locality I could name while my geography held out.

“Are you happy where you are?”

There was a vigorous and unanimous “No!” from the late Smiths.

” Is it warm there?”

An educated Smith seized the medium ‘s hand and wrote:

“It’s no name for it.”

“Did you leave any Smiths in that place when you came away? ”

” Dead loads of them ”

I fancied, I heard the shadowy Smiths chuckle at this feeble joke — the rare joke that there could be live loads of Smiths where all are dead.

“How many Smiths are present?”

“Eighteen millions — the procession now reaches from here to the other side of China.”

“Then there are many Smiths in the kingdom of the lost?”

“The Prince Apollyon calls all newcomers Smith on general principles; and continues to do so until he is corrected, if he chances to be mistaken.”

“What do lost spirits call their dread abode?”

” They call it the Smithsonian Institute.”

I got hold of the right Smith at last — the particular Smith I was after — my dear, lost, lamented friend — and learned that he died a violent death. I feared as much. He said his wife talked him to death. Poor wretch!

Twain left for greener pastures:

I have been engaged to write for the new literary paper – the “Californian’- same pay I used to receive at the Golden Era – one article a week, fifty dollars a month. I quit the Era long ago. It wasn’t high-toned enough.’

But he nonetheless resumed contributing articles to the Golden Era.

Bret Harte (1836-1902)

Bret Harte returned to San Francisco in 1857 and was hired by the Golden Era as a compositor. But Lawrence soon spotted his talent and asked him to write. Harte produced eleven poems and seventy-four sketches and articles.

In his poems and stories for the Golden Era and the Overland Monthly, he wove yarns and satirized the popular authors of the day. He edited a collection of California poetry and helped the young Sam Clemens with an early manuscript . Within a few years, he was the toast of San Francisco and a “hot property” being courted by publishers in Chicago, New York and Boston.

Harte’s reputation is built on a handful of stories and a poem that he wrote while living in San Francisco during the years of the Gold Rush. “Tennessee’s Partner,” “The Outcasts of Poker Flat,” “M’Liss,” and “The Luck of Roaring Camp” are some of the titles that brought him international fame and caused readers to call him “the young Dickens.”

Harte wrote sixteen chapters of M’liss for the Golden Era but left and did not complete it. (Harte went to the Californian, and hired Twain away from the Golden Era.) The Golden Era hired Gilbert Densmore to finish the story. Harte wrote the first 25,000 words, Densmore the final 135,000.

In 1873 Robert Dewitt of New York published M’Liss, listing Harte as the author. On page 34, where Harte’s writing ends, there was a note: “the remainder of this story was written by another hand than Bret Harte, but will be found equally interesting and able.” Harte disagreed, especially about the “able” part.

Harte was not happy with “this most patent fraud.” Harte had sold the copyright for the first chapters to Lawrence, but sued to stop sale of the book on the grounds that his name was a trademark, and the New York State Supreme Court agreed with him.

M’liss was made into a play. As American jurisprudence considered plays to be a new creative act, Harte had no standing, but the play was soon caught up in a tangle of lawsuits, one of which was heard in New York by Judge Lawrence (yes, yet another relation).

The Occidental Hotel

When Lawrence bought the Golden Era in 1860, he moved the office to the Occidental Hotel. There he began a “campaign of geniality and gin” to cultivate authors. He feted and got contributions from Albert Bierstadt and Sir Richard Burton, as well as from now forgotten authors.

Different visitors had different impression of the office, perhaps depending on how much time they had spent at the hotel bar.

One visitor remembered

the most grandly carpeted and most gorgeously furnished that I have ever seen. Even now in my memory they seem to have been simply palatial.

Another, however, had a different impression of an office that

boasted only two desks…numerous kitchen chairs in various stages of decrepitude. There may have been what was once a Brussels carpet on the floor, but if there was it was worn to the warp, and if it bore any figure which suggested a pattern it was that mentioned in a parody by Bret Harte, who said, “on each rock the fresh tobacco stain.”

The Occidental bar was famous. Hingston, the Englishman who was Artemus Ward’s agent, was impressed:

It is a commodious apartment, luxuriously appointed, scrupulously clean, and radiant with white marble, gilt fixtures, and glittering crystal.

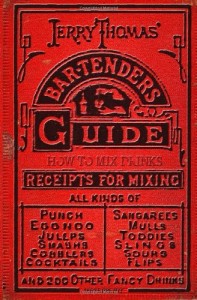

It was presided over by the famous bartender Jerry Thomas:

An author as well as an artist, who has written a work on the art of compounding drinks. He is clever also with his pencil as well as with his pen, and behind his bar are specimens of his skill as a draughtman. He is a gentleman who is all ablaze with diamonds. There is a very large pin, formed of a cluster of diamonds, in the front of his magnificent shirt, he has diamond studs at his wrists, and gorgeous diamond rings on his fingers.

In the manufacture of a “cocktail,” a “julep,” a “smash,’ or an “eye-opener,” none can beat him.

He made more money than the Vice President of the United States and wrote the first book on how to mix drinks.

He is credited with inventing the Tom and Jerry (probably not) and the Martini. Of the latter it is said

it is believed that the Martini was first invented at the Occidental Hotel. It evolved from a cocktail called the Martinez which was served to patrons who frequented the hotel before taking an evening ferry to the nearby town of Martinez.

But Thomas definitely invented the Blue Blazer.

Here is a modern version – do not try this at home.

Return East

Lawrence retired from the Golden Era in 1867 and returned east to Flushing, where he purchased one of the old Lawrence houses and took over the Flushing Journal. His sister, Lydia, the Spiritualist, contributed articles. He also had a position at the Custom House.

He presides with dignity over the Society for “the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals,” nurses the same old meerschaum and luxuriates on cold tea with a stick in it.”

He was active in the Society of California Pioneers.

Josquin Miller recounted the end time:

Lawrence came to me in New York a few years back leaning on the arm of Prentice Mulford. The courtly, handsome, heroic gentleman of the old heroic days was dying. I took them to the theater, for Lawrence seemed so very sad. His brain was failing him – sunstroke, he said, but he could not stay out of the play. He arose with something of his old-time courtliness, for there were ladies in the box, shook hands gently with us all. And then he and Mulford went out into the night and – beyond the night, please God.

Joseph Effingham Lawrence died at Toms River, New Jersey, on July 14, 1878. He had always been generous, and therefore left only a modest estate: some land, a half interest in the Golden Era, and a half interest in the Californian Magazine and Mountaineer. Everything went to his sister, Hannah T. Lawrence. He is buried in the Lawrence family plot in Flushing.