Allen Tupper Brown (1916-1944), the son of Clifton Stevenson Brown and Katherine Boyce Tupper, was born in 1916 and was twelve when his father was murdered in 1928.

After his widowed mother met George Marshall, Allen was not initially enthusiastic. His mother recounts

The next summer I told my sons that I had asked Colonel Marshall to visit us at Fire Island as I wanted him to know them. Clifton suspected something at once and said, “If it makes you happier, Mother, it is all right with me.” But Allen, then twelve, sad, “I don’t know about that, we are happy enough as we are.” Early the next morning he came to my room. “It is all right, Mother, about your asking Colonel Marshall.” That summer George told me that Allen had written him a most amusing letter in which he said, “I hope you will come to Fire Island. Don’t be nervous, it is OK with me. (Signed) A friend in need is a friend indeed. Allen Brown.” And they were friends until the end.”

Allen went to Gilman in Baltimore, and then to Woodberry Forest and the University of Virginia. He started in the promotion department of the New York Times in 1936.

Allen married Margaret “Madge” Goodman Shedden of Westchester; he was Katherine’s youngest child and the first to be married. They had one son, Allen Tupper Brown Jr. (Tupper), and lived on a farm house in Poughkeepsie.

In November 1942 Allen enlisted in the Armored Force. He went to OCS at Fort Knox, and in June 1943 graduated as a second lieutenant. Just before going to African in August 1943. Allen and Clifton and James Winn were at Dodona, the family house in Leesburg. There

Jim, a Regular Army officer, and Clifton, being a bit down in the mouth that Allen, the youngest and last in the service, was to be the first to get to the front. As we [the Marshalls] approached the Allen was saying, “why shouldn’t I go over first? I am a tanker, and the task lead the fight.”

Clifton broke in with, “Where would the tanks be without the Antiaircraft?”

Jim came back with, “Who clears the way for the tankers? – the Field Artillery.”C

For that dinner I had provided all of the things Allen like most.

After dinner we had quite a ceremony. In the field below the house I had dug up an old horseshoe, a rather small one that had probably been on the hoof of some ante-bellum lady’s riding mare. We gathered in front of the garage while Allen hung up the horseshoe, and we drank to his health once again. I recall that at first he hung the shoe with the points down A protest went up – his luck would run out – so it was taken down and while Madge held it in place Allen nailed it with the points up. The next morning he flew off for England on his way to the front.

2nd Lieutenant Allen Tupper Brown

On June 29, 1943 George wrote to his stepson, to whom he was very close. They had both gone to pains to conceal their relationship, lest Allen be the recipient of any favoritism. George, however, did intervene, against his own policy, after Allen graduated from OCS. George explained that

I feel quite differently about intervening in this way when it is a move to the front rather than the opposite.

That is, instead of protecting Allen, he had acceded to Allen’s desire to be sent to the front and put in danger.

Clifton and Allen were together at the battle of Monte Cassino and then Allen left for the Anzio Beachhead. Allen wrote

I feel sorry for any German in Italy. The horseshoe had held my luck. I shall take it down this Christmas and keep it for the rest of my life.

Sherman tanks disembarking at Anzio

Allen commanded a tank at Anzio.

Just after receiving these letters from Allen and Clifford on the morning before Decoration Day, George left for the office, but returned an hour later,

General Devers reported that at 10 AM on May 29, 1944 that near Campoleone

Allen was killed in action on the 29th while leading his platoon in an attack west of Velletri. He was shot by a sniper when he stood up in his turret to observe the front with his field glasses.

Other reports indicate the sniper through a hand grenade.

Clifton later told his mother that

He had reached the scene a few hours after Allen’s death and had been given permission to go to the front. Not wishing to expose a driver to unnecessary danger he had driven himself and talked to each man in Allen’s platoon. He has collected his brother’s belongings and attended his funeral on Decoration Day. Gathering some flowers in a near-by field he had placed them on Allen’s grave for Madge and me.

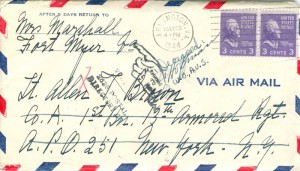

Here is the last letter that his mother wrote to Allen. It is marked “return to sender.”

Katherine went to Fire Island.

I went to my room and hanging in my closet was a black sweater, from Allen’s Woodberry days, with a big bock “W” in yellow. I opened my top drawer and a white box lay there. Removing the lid I found the box full of bronze medals such as little boys win at swimming races, and there along the medals was small gold football marked “Allen Tupper Brown.”

The Marshalls received hundreds of letters of condolence. George answered them all personally to spare Katherine. The one letter that brought Katherine some comfort said

Your son will always be young and unafraid, he will never have to grow old, he will never know such grief as yours.

Allen was Katherine’s youngest child and the first to die.

On June 20, 1944, George was in Italy and visited the Anzio cemetery and spent a half hour at Allen’s raw grave. He then went to the spot where Allen was killed. When George visited Pius XII in 1948, he and Katherine went to the Anzio military cemetery to visit Allen’s grave.

The American Cemetery

In July, 1937, Allen had written a letter to the New York Times:

When a man becomes of importance to the world is it necessary for him to forget the common decencies of life?

Should a man become so great that when encountering opposition to a cause that is of greatest interest his feelings should be so contorted as to let him dwarf the death of a friend and supporter beside an issue of political importance? Should any man become so great that into his personality creeps a slight stubbornness and a touch of ego that unbends to nothing, not even to death? How great is a great man?

Madge’s brother, Lt. Robert L. Shedden of the Army Air Force, had been killed while on a mission over Europe on January 22, 1943.

Madge married John White Pendleton (1908-1971), a VMI graduate and Rhodes scholar.

Allen Tupper Brown, Jr.

Tupper Jr. on left, with his cousins Kitty and Jimmy Winn

There is an Allen Tupper Brown who is still alive; he may be the surviving son.