and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.

Mount Calvary Church

A Roman Catholic Congregation of

The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Trinity XXI

Prelude

Prelude on ‘St. Columba’, Henry George Ley

Hymns

Praise to the Lord, the Almighty

The King of love my shepherd is

Praise, my soul, the King of heaven

Anthems

Lay me low, where the Lord can find me, Kevin Siegfried

Lord, give Thy Holy Spirit, Thomas Tallis

Common

Missa de S. Maria Magdalena, Willan

Postlude

Kleines Harmonisches Labyrinth, J. S. Bach (?)

_____________________________________

PRELUDE

Prelude on St. Columba, Henry George Ley

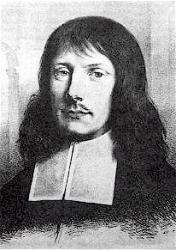

Henry George Ley

Henry George Ley MA DMus FRCO FRCM HonRAM (1887 – 1962) was an English organist, composer and music teacher.

Dr Ley was born in Chagford in Devon. He was a chorister at St George’s Chapel Windsor Castle, Music Scholar at Uppingham School, Organ Scholar of Keble College Oxford (1906) where he was President of the University Musical Club in 1908, and an Exhibitioner at the Royal College of Music where he was a pupil of Sir Walter Parratt and Marmaduke Barton. He was organist at St Mary’s, Farnham Royal, from 1905–1906, and at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford (1909–1926), Professor of organ at the Royal College of Music in London from 1919, and Precentor at Radley College and at Eton College (that is, in charge of the music in College Chapel) from 1926 to 1945. He was an Honorary Fellow of Keble College, Oxford, from 1926 to 1945 and died on 24 August 1962. He was a composer of choral works, including a celebrated setting of the Founder’s Prayer of King Henry VI.

Here is the Prayer.

_____________________________

HYMNS

Praise to the Lord, the Almighty (#279), a paraphrase of Psalms 103 and 150, was written by Joachim Neander (1650—1680), the first hymn writer of the German Reformed Church. A valley was renamed in his honor in the early nineteenth century, and later became very famous in 1856 because of the discovery of the remains of Homo neanderthalensis, or the Neanderthal discovered in that valley.

The hymn was Englished by the indefatigable translator of German hymns, Catherine Winkworth (1827—1878). She began translating hymn texts into the English language during the early years of the Oxford movement. Leaders of the Oxford movement believed that the English Reformation had gone too far and had thrown out much that was valuable in the pre-16th century church. They realized that hymns had been a significant part of worship, and they revived Greek hymns from the early years of the church, Latin hymns from the Roman Catholic Church, and German hymn texts from the Lutheran Reformation.

The 1940 Hymnal uses 1,2, 4, and 5.

Praise to the Lord, the Almighty,

the King of creation!

O my soul, praise Him, for He is thy

health and salvation!

All ye who hear,

Now to His temple draw near;

Sing now in glad adoration!

2

Praise to the Lord, who o’er all

things so wondrously reigneth,

Who, as on wings of an eagle,

uplifteth, sustaineth.

Hast thou not seen

How thy desires all have been

Granted in what He ordaineth?

3

Praise to the Lord, who hath fearfully,

wondrously, made thee!

Health hath vouchsafed and, when

heedlessly falling, hath stayed thee.

What need or grief

Ever hath failed of relief?

Wings of His mercy did shade thee.

4

Praise to the Lord, who doth prosper

thy work and defend thee,

Who from the heavens the streams of

His mercy doth send thee.

Ponder anew

What the Almighty can do,

Who with His love doth befriend thee.

5

Praise to the Lord! Oh, let all that

is in me adore Him!

All that hath life and breath, come

now with praises before Him!

Let the Amen

Sound from His people again;

Gladly for aye we adore Him.

Here is the hymn at the 6oth anniversary of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth.

Here is the German:

Lobe den Herren,

den mächtigen König der Ehren,

meine geliebete Seele,

das ist mein Begehren.

Kommet zuhauf,

Psalter und Harfe, wacht auf,

lasset den Lobgesang hören!Lobe den Herren,

der alles so herrlich regieret,

der dich auf Adelers

Fittichen sicher geführet,

der dich erhält,

wie es dir selber gefällt;

hast du nicht dieses verspüret?Lobe den Herren,

der künstlich und fein dich bereitet,

der dir Gesundheit verliehen,

dich freundlich geleitet.

In wieviel Not

hat nicht der gnädige Gott

über dir Flügel gebreitet!Lobe den Herren,

der deinen Stand sichtbar gesegnet,

der aus dem Himmel

mit Strömen der Liebe geregnet.

Denke daran,

was der Allmächtige kann,

der dir mit Liebe begegnet.Lobe den Herren,

was in mir ist, lobe den Namen.

Alles, was Odem hat,

lobe mit Abrahams Samen.

Er ist dein Licht,

Seele, vergiss es ja nicht.

Lobende, schließe mit Amen!

Her is the Bach’s version at Erfurt.

Joachim Neander

Joachim Neander (1650-1680)was the grandson of a musician and son of a teacher. He studied theology at Bremen University from 1666 to 1670. His family name was Neumann (“new man”), but, as was popular at the time, his grandfather (also a preacher, and also named Joachim!), changed it to a foreign equivalent, in this case Greek. In 1671, Neander moved his studies to Heidelberg (locale of The Student Prince musical). In 1673, he moved to Frankfurt, where he met Pietistic scholars Philipp Jakob Spener (1635-1705) and Johann Schütz (1640-1690).

Düssel River

From 1674 to 1679, Joachim Neander was principal of the Reformed Lateinschule (grammar school) in Düsseldorf. During these years, he used to wander the secluded Düssel River valley, which was, until the 19th Century, a deep ravine between rock faces and forests, with numerous caves, grottos and waterfalls. In the early 19th Century, a large cave was named Neanderhöhle after him. In the mid-19th Century, the cement industry started to quarry the limestone, and the narrow ravine became a wide valley, which was now named the Neander Valley (in German, Neanderthal). The “Neanderthal Man” was found there in the summer of 1856, giving Joachim the distinction of being the only hymnist with a fossil hominid (or any fossil) named after him.

My Ancestor

In 1679, Joachim Neander moved to Bremen and worked as assistant preacher at St. Martini church. The next year he became seriously ill and died, presumably of the plague.

The anonymous tune LOBE DEN HERRN appeared in the 1665 edition of Praxis pietatis melica (Practice of Piety in Song). a Protestant hymnal first published in the 17th century by Johann Crüger. The hymnal, which appeared under this title from 1647 to 1737 in 45 editions, has been described as “the most successful and widely-known Lutheran hymnal of the 17th century”

____________________________

Henry Williams Baker (1821-1877) recast George Herbert’s metrical paraphrase of Psalm 23 into this hymn, The King of love my shepherd is (#345, First tune). Baker gives Psalm 23 an explicit Christological and sacramental cast. “The streams of living water” flow from Jesus’ pierced side. He ransoms our soul from the captivity of sin, and feeds with food celestial, “the bread which cometh down from heaven, that a man may eat thereof, and not die” On our own we never keep to the righteous paths. That is why Jesus comes in love to us, sinners as we are. In his persistent and tender mercy Jesus seeks us, when, “perverse and foolish,” we stray from Him. The wood of the shepherd’s staff is the wood of the cross that guides the strayed soul. Delights flow from Jesus’ pure chalice. The “wine that gladdens the heart” is the Eucharist, the blood of Christ; His is the chalice that overbrims with love. In the Old Testament, our ancestors in faith longed to dwell in the “house of the Lord,” before the revelation of eternal life was clear. But now Christ fulfills that mysterious longing. He is the Good Shepherd, who “giveth his life for the sheep,” the ultimate gift, eternal life with Him. (Thanks to Tony Esolen)

Here is a Reformed analysis of the hymn:

“We note immediately that the usual way of naming God (“the Lord”) has been replaced with a nonbiblical yet immediately comprehensible allegorical title, “the King of Love.” This unfamiliar opening and the inversion in the first line (“my shepherd is”) prepare the singer for a text that is intentionally—even self-consciously—allusive and aesthetic. This perception of the text is reinforced by the archaic verb forms (“leadeth,” “feedeth”) and the Latinate diction (“verdant,” “celestial”) in the second stanza. The third stanza intensifies the Christological overtones of this paraphrase with allusions not only to the Good Shepherd passage noted earlier but also to Jesus’ parable of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:4-7; cf. Matthew 18:12-14). The fourth stanza follows the biblical shift from third person to second person, but adds to the images of the shepherd’s rod and staff the suggestion of a processional cross familiar to many nineteen-century Anglican congregations. There is a similar churchy slant in the fifth stanza, where the psalter’s “oil” takes on sacramental tones by being called “unction,” and the usual English translation “cup” becomes a comparably Latinate and ecclesiastical “chalice.” As a result, the reference to God’s “house” in the final line of the sixth stanza does not suggest the Temple in Jerusalem so much as it does the church building in which the hymn is being sung.” (ReformedWorship.org)

I doubt that in the last line “Thy house” is simply the church building; heaven is clearly meant and specified by the “forever.” Anglocatholic services are long, but not that long.

1 The King of love my shepherd is,

whose goodness faileth never.

I nothing lack if I am his,

and he is mine forever.2 Where streams of living water flow,

my ransomed soul he leadeth;

and where the verdant pastures grow,

with food celestial feedeth.3 Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.4 In death’s dark vale I fear no ill,

with thee, dear Lord, beside me;

thy rod and staff my comfort still,

thy cross before to guide me.5 Thou spreadst a table in my sight;

thy unction grace bestoweth;

and oh, what transport of delight

from thy pure chalice floweth!6 And so through all the length of days,

thy goodness faileth never;

Good Shepherd, may I sing thy praise

within thy house forever.

Here is the Cardiff Festival Choir singing the hymn. Here is John Rutter’s lovely arrangement with harp accompaniment.

Henry Williams Baker

Sir Henry Williams Baker was the eldest son of Admiral Sir Henry Loraine Baker. Henry was born in London, May 27, 1821, and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated, B.A. 1844, M.A. 1847. Taking Holy Orders in 1844, he became, in 1851, Vicar of Monkland, Herefordshire. This benefice he held to his death, on Monday, Feb. 12, 1877. He succeeded to the Baronetcy in 1851. His hymns, including metrical litanies and translations, number in the revised edition of Hymns Ancient & Modern, 33 in all.. The last audible words which lingered on his dying lips were the third stanza of his rendering of the 23rd Psalm, “The King of Love, my Shepherd is:”—

Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.

This tender sadness, brightened by a soft calm peace, was an epitome of his poetical life.

The tune is ST COLUMBA. Because the compilers of the 1906 English Hymnal were denied permission to use Dykes’s original tune, musical editor Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) turned to a folk tune that his former teacher Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) had recently edited for a collection of Irish music (A Complete Collection of Irish Music as noted by George Petri (London, 1902-1905); ST. COLUMBA is no. 1043). The two most notable improvements Vaughan Williams made in the hymn tune known as ST. COLUMBA were the lengthening of the second and fourth lines to extend the Common Meter tune to 8787 in order to accommodate Baker’s text—this being their first appearance together—and the use of a triplet (rather than an eighth and two sixteenths) in the sixth measure. (ReformedWorship.org).

The words of this hymn are often subjected to “modernization,” a process that frequently obscures the meaning the poet intended. For example, a 1994 Lutheran hymnal changes

Thou spreadst a table in my sight;

thy unction grace bestoweth;

and oh, what transport of delight

from thy pure chalice floweth!

to

You spread a table in my sight,

A banquet here bestowing;

Your oil of welcome, my delight;

My cup is overflowing!

The clear allusion to the Eucharistic chalice has been almost completely obscuresd and the deep emotion of “transports of delight” toned down and transferred to oil, which might be a reference to the oil used at baptism, if Lutherans use, it, but it is very obscure.

On a personal note, I have used the hymn at the funeral masses I have arranged for member of my family: my mother, my nephew, my sister. I think the hymn combines the sweetness, sadness, and tender trust that we feel when a fellow Christian leaves this life to enter into the presence of the Lord.

We mourn, not as those who have no hope, but we do and should mourn.

When I was walking the Camino de Santiago in 2010, I passed through a pastoral landscape in which shepherds with their staffs were leading flocks of sheep. I sang this hymn, with especial stress on the stanza,

Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.

On the Camino I had the strong feeling that I was on my way Home; if I could not walk, I would be carried.

____________________________

Praise my soul the King of heaven (#282) by the Anglican clergyman Henry Francis Lyte (1793—1847) is, like the first hymn, a paraphrase of Psalm 103.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the pressure was on hymn writers to keep their versifications of psalms as close to the Scriptural text as possible. Henry F. Lyte would have none of this, and boldly published a book of psalm paraphrases entitled Spirit of the Psalms. Lyte decided he could maintain the spirit of the psalms while still using his own words, probably with the intention of making the reader see the psalms in a new light. Lyte’s text speaks to the love of God and our dependence on Him in a clear and imaginative way.

1 Praise, my soul, the King of heaven;

to his feet your tribute bring.

Ransomed, healed, restored, forgiven,

evermore his praises sing.

Alleluia, alleluia!

Praise the everlasting King!

2 Praise him for his grace and favor

to his people in distress.

Praise him, still the same as ever,

slow to chide, and swift to bless.

Alleluia, alleluia!

Glorious in his faithfulness!

3 Fatherlike he tends and spares us;

well our feeble frame he knows.

In his hand he gently bears us,

rescues us from all our foes.

Alleluia, alleluia!

Widely yet his mercy flows!

4 Angels, help us to adore him;

ye behold him face to face.

Sun and moon, bow down before him,

dwellers all in time and space.

Alleluia, alleluia!

Praise with us the God of grace!

Henry Francis Lyte

Henry Francis Lyte (also the author of Abide with me) was the second son of Thomas and Anna Maria (née Oliver) Lyte. He was born at Ednam, near Kelso, Scotland. Lyte’s father was described as a “ne-er do-well … more interested in fishing and shooting than in facing up to his family responsibilities”. He deserted the family shortly after making arrangements for his two oldest sons to attend Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh; and Anna moved to London, where both she and her youngest son died.

The headmaster at Portora, Dr. Robert Burrowes, recognised Henry Lyte’s ability, paid the boy’s fees, and “welcomed him into his own family during the holidays.” Lyte was effectively an adopted son.

After studying at Trinity College, Dublin and with very limited training for the ministry, Lyte took Anglican holy orders in 1815, and for some time he held a curacy in Taghmon near Wexford. Lyte’s “sense of vocation was vague at this early stage. Perhaps he felt an indefinable desire to do something good in life.” However, in about 1816, Lyte experienced an evangelical conversion. In attendance on a dying priest, the latter convinced Lyte that both had earlier been mistaken in not having taken the Epistles of St. Paul “in their plain and literal sense.” Lyte began to study the Bible “and preach in another manner,” following the example of four or five local clergymen whom he had previously laughed at and considered “enthusiastic rhapsodists.”

In 1817 Lyte became a curate in Marazion, Cornwall, and there met and married Anne Maxwell, daughter of a well-known Scottish-Irish family. She was 31, seven years older than her husband and a “keen Methodist.” Furthermore, she “could not match her husband’s good looks and personal charm.” Nevertheless, the marriage was happy and successful. Ann eventually made Lyte’s situation more comfortable by contributing her family fortune, and she was an excellent manager of the house and finances. They had two daughters and three sons, one of whom was the chemist and photographer Farnham Maxwell-Lyte. A grandson was the well known historian Sir Henry Churchill Maxwell-Lyte.

From 1820 to 1822 the Lytes lived in Sway, Hampshire. Itself only five miles from the sea, the house in Sway was the only one the couple shared during their marriage that was neither on a river or by the sea. At Sway Lyte lost a month-old daughter and wrote his first book, later published as Tales In Verse Illustrative of the Several Petitions of the Lord’s Prayer (1826). In 1822 the Lytes moved to Dittisham, Devon, on the River Dart and then, after Lyte had regained some measure of health, to the small parish of Charleton.

About April 1824, Lyte left Charleton for Lower Brixham, a Devon fishing village. Almost immediately, Lyte joined the schools committee, and two months later he became its chairman. Also in 1824, Lyte established the first Sunday school in the Torbay area and created a Sailors’ Sunday School. Although religious instruction was given there, the primary object of both was educating children and seamen for whom other schooling was virtually impossible. Each year Lyte organised an Annual Treat for the 800-1000 Sunday school children, which included a short religious service followed by tea and sports in the field.

Shortly after Lyte’s arrival in Brixham, the minister attracted such large crowds that the church had to be enlarged—the resulting structure later described by his grandson as “a hideous barn-like building.” Lyte added to his clerical income by taking resident pupils into his home, including the blind brother of Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, later British prime minister. About 1830, Lyte made excavations at nearby Ash Hole Cavern, where he discovered pottery and human remains.

Lyte was a tall and “unusually handsome” man, “slightly eccentric but of great personal charm, a man noted for his wit and human understanding, a born poet and an able scholar.” He was an expert flute player and according to his great-grandson always had his flute with him. Lyte spoke Latin, Greek, and French; enjoyed discussing literature; and was knowledgeable about wild flowers. At Berry Head House, a former military hospital at Berry Head, Lyte built a magnificent library —largely of theology and old English poetry—described in his obituary as “one of the most extensive and valuable in the West of England.”

Nevertheless, Lyte was also able to identify with his parish of fishermen, visiting them at their homes and on board their ships in harbour, supplying every vessel with a Bible, and compiling songs and a manual of devotions for use at sea. In theology Lyte was a conservative evangelical who believed that man’s nature was totally corrupt. Lyte frequently rose at 6 AM and prayed for two or more hours before breakfast.

In politics, Lyte was a Conservative who feared revolt among the irreligious poor. He publicly opposed Catholic Emancipation by speaking against it in several Devon towns, stating that he preferred Catholics to be “emancipated from priests and from the power of the factious and turbulent demagogues of Ireland.” Lyte, a friend of Samuel Wilberforce, also opposed slavery, organising an 1833 petition to Parliament requesting it be abolished in Great Britain.

In poor health throughout his life, Lyte suffered various respiratory illnesses and often visited continental Europe in attempts to check their progress. In 1835 Lyte sought appointment as the vicar of Crediton but was rejected because of his increasingly debilitating asthma and bronchitis. In 1839, when only 46, Lyte wrote a poem entitled “Declining Days.” Lyte also grew discouraged when numbers of his congregation (including in 1846, nearly his entire choir) left him for Dissenter congregations, especially the Plymouth Brethren, after Lyte expressed High Church sympathies and leaned towards the Oxford Movement.

By the 1840s, Lyte was spending much of his time in the warmer climates of France and Italy, making written suggestions about the conduct of his family’s financial affairs after his death. When his daughter was married to his senior curate, Lyte did not perform the ceremony. Lyte complained of weakness and incessant coughing spasms, and he mentions medical treatments of blistering, bleeding, calomel, tartar emetic, and “large doses” of Prussic acid. Yet his friends found him buoyant, cheerful, and keenly interested in affairs of the Europe around him. Lyte spent the summer of 1847 at Berry Head then, after one final sermon to his congregation on the subject of the Holy Communion, he left again for Italy. He died on 20 November 1847 at Nice, at that time in the Kingdom of Sardinia, where he was buried.

John Goss composed LAUDA ANIMA (Latin for the opening words of Psalm 103) for this text in 1868. Along with his original harmonizations, intended to interpret the different stanzas, the tune was also included in the appendix to Robert Brown¬ Borthwick’s Supplemental Hymn and Tune Book (1869). LAUDA ANIMA is one of the finest tunes that arose out of the Victorian era. A reviewer in The Musical Times, June 1869, said, “It is at once the most beautiful and dignified hymn tune which has lately come under our notice.”

John Goss

Sir John Goss (27 December 1800 – 10 May 1880) was an English organist, composer and teacher.

Born to a musical family, Goss was a boy chorister of the Chapel Royal, London. The master of the choir at that time was John Stafford Smith, a musician known for composing the song To Anacreon in Heaven, later used as the tune of the American national anthem. As an educator, Smith combined a harsh discipline with a narrow musical curriculum. He confiscated Goss’s score of Handel’s organ concertos on the grounds that choristers of the Chapel Royal were there to learn to sing and not to play.

Goss was later a pupil of Thomas Attwood, organist of St Paul’s Cathedral. After a brief period as a chorus member in an opera company he was appointed organist of a chapel in south London, later moving to more prestigious organ posts at St Luke’s Church, Chelsea and finally St Paul’s Cathedral, where he struggled to improve musical standards.

Attwood died in 1838, and Goss hoped to succeed him as organist of St Paul’s. He sought the advice of the Rev Sydney Smith, canon of St Paul’s, who teased him by telling him that the salary was only £34 a year. Having a family to support, Goss replied that he might not be able to apply for the post, but Smith then revealed that the post of organist carried with it several additional sources of income, which enabled Goss to reconsider. He was appointed to the post, but immediately found that the organist was employed solely to play the organ, and enjoyed little influence over the other music of the cathedral. Control of the music lay with the Succentor, Canon Beckwith, who was at odds with the Almoner, Canon Hawes, who was responsible for rehearsing the boy choristers. The cathedral authorities were not interested in raising musical standards. Sydney Smith’s view was typical: “It is enough if our music is decent … we are there to pray, and the singing is a very subordinate consideration.” Some of Smith’s colleagues were indifferent to both considerations, there being frequent absenteeism by the junior clergy, neglecting their duties and failing to conduct services.

Goss was noted for his piety and gentleness of character. His pupil, John Stainer, wrote, “That Goss was a man of religious life was patent to all who came into contact with him, but an appeal to the general effect of his sacred compositions offers public proof of the fact.” His mildness was a disadvantage when attempting to deal with his recalcitrant singers. He was unable to do anything about the laziness of the tenors and basses, who had lifetime security of tenure and were uninterested in learning new music.[10] The biographer Jeremy Dibble writes, “Hostility to [Goss’s] fine anthem ‘Blessed is the man’, composed in 1842, undermined his confidence so markedly that he did not compose any further anthems until 1852, when he was commissioned to write two anthems for the state funeral of the Duke of Wellington”.

Stainer who was a boy chorister at the time of Wellington’s funeral later recalled the effect of Goss’s music at rehearsal: “When the last few bars pianissimo had died away, there was a profound silence for some time, so deeply had the hearts of all been touched by its truly devotional spirit. Then there gradually arose on all sides the warmest congratulation to the composer, it could hardly be termed applause, for it was something much more genuine and respectful.” Stainer was not always so reverential about his teacher. He later recalled the occasion on which he and the young Arthur Sullivan succumbed to laughter when Goss absent-mindedly walked across the pedals of the organ during a service “before he realised that he was the cause of the alarming thunderings which were frightening the congregation and putting a temporary pause in the sermon.”

_____________________________

ANTHEMS

Lay me low, Kevin Siegfried

Lay me low, lay me low. Where the Lord can find me, Where the Lord can own me, Where the Lord can bless me.

This Shaker Song was written ca. 1838 by Addah Z. Potter in the Shaker community at New Lebanon, NY. Lay me Low is Kevin Siegfried’s arrangement, from his Shaker Songs.

Here is a performance at the University of Missouri. Here is his lovely arrangement of the familiar Love is Little.

Kevin Siegfried

Acclaimed as writing music of “austere beauty” that exhibits the “pressure and presence of personal conviction,” Kevin Siegfried (b. 1969) is in demand as a composer of distinctive and engaging musical works. His music was recently described as “hypnotic and beautifully written” by The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and is known for its direct expression, lyricism, and accessibility.

Siegfried is actively involved in the research and performance of early American music and his arrangements of Shaker music have been performed and recorded by choirs across the globe. The Tudor Choir’s “Gentle Words” CD, the premiere recording of Siegfried’s Shaker arrangements, received wide acclaim and was praised as “a stunning addition to the repertoire” by Fanfare Magazine.

Siegfried teaches at The Boston Conservatory, where he is Coordinator of Theory and New Works in the Theater Division, and directs the Songwriting Workshop, a training ground for budding songwriters in a variety of styles. Siegfried graduated from The New England Conservatory with a Doctor of Musical Arts degree in composition. He studied additionally in Paris, through the European American Musical Alliance, and in India, having received a Stanley Fellowship to study South Indian classical music with performing artist Sriram Parasuram. His previous teaching experience includes Harvard University, The New England Conservatory, The University of Iowa, and The Northwest School in Seattle.

O Lord, give Thy Holy Spirit, Thomas Tallis (1505-1585)

O Lord, give thy Holy Spirit into our hearts, and lighten our understanding, that we may dwell in the fear of thy Name, all the days of our life, that we may know thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom thou hast sent.

Here is a Spanish group.

___________________________

Postlude

Kleines Harmonisches Labyrinth, J. S. Bach (?)

This composition is still listed in many works lists — old ones, albeit — as the doing of J.S. Bach. Almost all musicologists today, however, recognize it as at least of spurious provenance, and the majority of them assign the work to composer and Bach contemporary Johann David Heinichen (1683-1729), a man well-known in his lifetime but who faded to total obscurity until his rediscovery in the 1990s by conductor and musicologist Reinhard Goebel. The work was probably originally attributed to Bach because it contains the musical representation of his name (B flat, A, C, B natural) near the end of the piece, a motif that appears in some Bach pieces. Other composers also used it to pay homage to Bach.

The title of the work in English is usually translated as “Little harmonic labyrinth.” Lasting three minutes or so, the piece is in three sections: Introitus, Centrum, and Exitus, tempo Andante. It opens with a dramatic trill, then, while initially retaining the propulsive trill in the background, gradually moves from a festive mood to a hymn-like solemnity. The Centrum section is livelier and features interesting contrapuntal activity. The final section, the Exitus, makes up about half the length of the work. It initially harkens back to the Introitus in mood, but builds to a resoundingly triumphant ending, with sonorities moving higher and higher on the registers, as if reaching to the heavens.

Here is a view which sees it as Bach’s:

The Kleines harmonisches Labyrinth (BWV 591) by Johann Sebastian Bach has 3 parts: Introïtus – Centrum – Exitus. Analysis of the form and the harmony of the composition can lead to a view of the first 13 measures of the composition as the labyrinth. In the short polyphonic section which succeeds it the wanderer might be represented by the (descending) minor second. The passage work, alternating with chords, represents the walk through the labyrinth, in which the wanderer arrives at the Centrum. In the meditative Centrum movement the minor second (metaphor for the wanderer) is used both rising and falling, and chords with many accidentals are eschewed since these chords symbolize the hedges of the labyrinth. The Exitus proceeds more quietly than the Introïtus.

With his labyrinth composition Bach joined the discussion on the significance of the relationship mi-fa (minor second). BWV 591 should perhaps be viewed theologically against the background of an old sacred tradition in which the labyrinth is a metaphor for the soul in its arduous life’s journey (cf. also the mi-fa interval). Bach has as it were equated in his composition the arcanum Divinum (=divine mystery) of ‘fa-mi et mi-fa est tota Musica’ [fa-mi & mi-fa is all of Music] and the arcanum Divinum of the grace of God’s Word.

Here is Peter Hurford at the organ.