James Lawrence by Gilbert Stewart

U.S. Naval Academy Museum

Captain James Lawrence, the source of the navy’s motto Don’t give up the ship! is probably the most famous of my wife’s relatives. He is her third cousin, six times removed.

He was born on October 1, 1781 in Burlington, New Jersey, in this house:

He married Julia Montaudevert and had two children, Mary Neil (1810-1843) and James Montaudevert (1813-1814).

Julia Montaudevert

Descendant of French Privateers in the Indian Ocean

This is the official story (from Wikipedia). James was the

son of John and Martha (Tallman) Lawrence. His mother died when he was an infant and his Loyalist father fled to Canada during the American Revolution, leaving his half-sister to care for the infant. Though Lawrence studied law, he entered the United States Navy as a midshipman in 1798.

During the Quasi-War with France, he served on USS Ganges and the frigate USS Adams in the Caribbean. He was commissioned a lieutenant on April 6, 1802 and served aboard USS Enterprise in the Mediterranean, taking part in a successful attack on enemy craft on 2 June 1803.

In February 1804, he was second in command during the expedition to destroy the captured frigate USS Philadelphia. Later in the conflict he commanded Enterprise and a gunboat in battles with the Tripolitans. He was also First Lieutenant of the frigate Adams and, in 1805, commanded the small Gunboat No. 6 during a voyage across the Atlantic to North Africa.

Although Gunboats No. 2 through 10 (minus No. 7) arrived in the Mediterranean too late to see action, they remained there with Commodore Rodgers’s squadron until summer 1806, at which time they sailed back to the United States. On 12 June 1805 Gunboat No. 6 encountered a Royal Navy vessel that impressed three seamen.

Subsequently, Lieutenant Lawrence commanded the warships USS Vixen, USS Wasp and USS Argus. In 1810, he also took part in trials of an experimental spar torpedo. Promoted to the rank of Master Commandant in November 1810, he took command of the sloop of war USS Hornet a year later and sailed her to Europe on a diplomatic mission. From the beginning of the War of 1812, Lawrence and Hornet cruised actively, capturing the privateer Dolphin in July 1812. Later in the year Hornet blockaded the British sloop HMS Bonne Citoyenne at Bahia, Brazil, and on 24 February 1813 captured HMS Peacock.

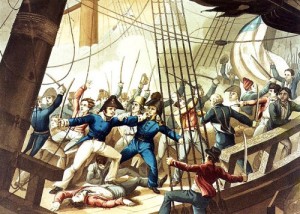

USS Chesapeake

Upon his return to the United States in March, Lawrence learned of his promotion to Captain. Two months later he took command of the frigate Chesapeake, then preparing for sea at Boston. He left port on 1 June 1813 and immediately engaged the blockading Royal Navy frigate Shannon in a fierce battle.

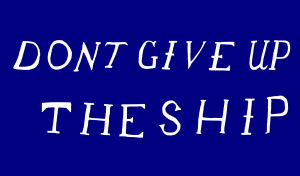

Although slightly smaller, the British ship disabled Chesapeake with gunfire within the first few minutes. Captain Lawrence, mortally wounded by small arms fire, ordered his officers, “Don’t give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks.” Or “Tell them to fire faster; don’t give up the ship.”

Men carried him below, and his crew was overwhelmed by a British boarding party shortly afterward. James Lawrence died of his wounds on 4 June 1813, while his captors directed Chesapeake to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

After Lawrence’s death was reported to his friend and fellow officer Oliver Hazard Perry, he ordered a large blue battle ensign, stitched with the phrase “Dont Give Up The Ship” in bold white letters. The Perry Flag was displayed on his flagship during a victorious engagement against the British on Lake Erie in September 1813. The original flag is displayed in the Naval Academy Museum and a replica is displayed in Memorial Hall at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. A replica is also on view at Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial, on South Bass Island, Ohio.

Lawrence was buried with military honors at present-day CFB Halifax, Nova Scotia, but reinterred at Trinity Church Cemetery in New York City.

He was survived by his wife, Julia (Montaudevert) Lawrence, who lived until 1865, and their two-year-old daughter, Mary Neill Lawrence. In 1838 Mary married a Navy officer, Lt. William Preston Griffin.

Here is my wife at her cousin’s grave:

A British designer who creates historically correct clothing has recreated the clothing of Lawrence and his British opponents as her master’s thesis:

James Lawrence’s uniform

Captain James Lawrence, USN. ~ Seaman Robert Bates, USN. ~ Captain Philip Bowes Vere Broke, RN. ~ Bo’s’un William Stevens, RN

A great story. It gave the American Navy a hero and a motto. But someone has given a different version of Lawrence’s last battle:

Tom Halsted, a Gloucester writer and sailor, is the great-great-grandson of James Curtis, a midshipman who, as a 15-year-old, was Lawrence’s aide-de-camp on the Chesapeake. Halsted in this article in the Globe described what actually happened:

Given the way it has echoed through the years, you might think Lawrence’s memorable plea marked a heroic moment in the history of American armed forces. It didn’t. Not only did Lawrence’s surviving crew give up the ship almost immediately after his exhortation, but historians and military analysts would later conclude that Lawrence had disobeyed orders to avoid combat in the first place, then committed a series of tactical blunders that all but guaranteed he and his ship would lose.

Rather than a heroic stand, what took place that day and after was one of the most spectacular—and fraudulent—public relations coups in American military history. It was carried out with the full support of the public. And to look back on what really happened, as it has been pieced together by historians since, is to appreciate how little has changed about one aspect of war: our need to transform even the most pointless losses into a noble, defiant message.

IF TELEVISION had existed, the battle between the Shannon and the Chesapeake would have been a prime-time event. The skirmish took place about a year into the War of 1812, which had broken out over several grievances with Britain, including onerous trade restrictions imposed by the British and the illegal boarding of American vessels in search of British deserters. Once war was declared, the British Royal Navy began hobbling American trade by blockading ports, including Boston, with warships based in Nova Scotia.

In late May 1813, Captain Philip Broke sailed the HMS Shannon, flagship of the blockading British squadron, into Massachusetts Bay alone, knowing the Americans had only one frigate ready for sea in Boston. On June 1, the Chesapeake rose to the bait.

Unlike most sea battles, which take place far from land, the whole encounter seemed made for public consumption. Spectators lined the rooftops in Boston and along the North Shore, and commanders of both ships repeatedly had to warn a boisterous spectator fleet of yachts and small boats to stay clear.

The first shot was fired at 6 p.m., the last at 6:11. The colors were struck at 6:15. The roar of cannon fire, the stabbing flames from the cannons’ mouths, and the smoke of battle could be heard and seen all along the coast.

Nearly every American observing the preparation for battle was confident the Americans would win. American ships had astonished the world in recent months by repeatedly defeating supposedly superior British naval forces, starting when the US frigate Constitution defeated the HMS Guerrière.

In Boston, plans were laid for a banquet to celebrate the anticipated victory of the Chesapeake over the Shannon, including places at the table for the defeated British officers. But none of the unnecessary defeat. He had had strict orders to avoid contact with the enemy and instead to slip through their blockade in order to harass enemy merchant ships in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. These he totally disobeyed, losing a frigate and his life in the process.

His famous exhortation, too, was breached immediately. With no American officers on deck to formally surrender, the British officers now in command of the Chesapeake’s quarterdeck simply declared the fighting over, raised the British colors over the American flag, and imprisoned the surviving American crewmen below decks. The two ships sailed off in tandem to the British naval headquarters in Halifax, Nova Scotia, leaving the American spectators dumbfounded.

No American heroes emerged from the engagement. The first and second lieutenants were wounded, the fourth lieutenant killed. Third Lieutenant William Cox was never able to regain the deck after taking Lawrence below, and was therefore made the scapegoat, convicted of leaving his place of duty, and dismissed from the Navy in disgrace. (His family and descendants tried for years to clear his name. Finally, in 1952, President Truman pardoned Cox and posthumously restored him to his former rank.)

Lawrence died en route to Halifax. Having committed a succession of bad decisions that all but guaranteed the loss of his ship and many of her crew, he should have been disgraced. Instead, he was lionized: given a funeral in Canada with full military honors, buried there, then disinterred and brought back to Boston for another funeral, reburied in Salem, dug up once more, and finally buried for good at Trinity Church in New York.

Though the true disgrace was Lawrence’s, the American public would not allow it. They had wanted a victory on June 1, and if they could not have a victory, at least they wanted a hero—and a story that helped them find nobility in defeat. The details of the war might seem distant, but the impulse to create heroes in the wake of pointless loss is as familiar as Custer’s Last Stand or the saga of Pat Tillman in Afghanistan. Two centuries ago, we were already seeing the picture we wanted—and, in that spirit, Lawrence’s failures were forgotten and his memory reshaped to position him as the hero he always wanted to be.

What really happened in war is often very difficult to ascertain. Did Lawrence act imprudently at the end of his career, The Naval History blog of the U. S Naval Institute tells this version of the event:

One American officer who contributed to these early triumphs over the Royal Navy was James Lawrence. On 24 February 1813, Lawrence’s sloop of war Hornet reduced HM brig-sloop Peacock to a sinking state in the space of fifteen minutes, killing and wounding more than a quarter of its crew. In recognition of this win, Lawrence was promoted to captain and given command of the frigate Chesapeake, then lying at Boston. Among the missions the Navy Department contemplated for Chesapeake at this time was the seizure and destruction of British transports and supply ships en route from England to Canada.

When Lawrence arrived in Boston on 20 May to assume command of Chesapeake he found his ship short of men and still in need of refitting for its intended voyage. He also discovered two British frigates cruising in the waters off Boston Harbor, awaiting the opportunity to intercept and capture any American vessel attempting to enter or depart from that port. By the 25th, only one British warship, the frigate Shannon, remained in view blockading the harbor.

Lured by the prospect of laurels in another single-ship combat with the enemy, and anxious to engage Shannon before that ship was reinforced, Lawrence hastened to ready Chesapeake for battle. Although Chesapeake and Shannon were nearly evenly matched in size and power, the latter vessel held a decided advantage over its American counterpart in unit cohesiveness and training, especially gunnery. On 1 June when Lawrence sailed Chesapeake out to meet Shannon, he had directed his crew for less than two weeks, while Shannon’s captain, Philip Broke, had commanded his vessel for seven years.

This disparity in experience and service gave the well-trained Shannons the edge in the battle that ensued. After a hard-fought, bloody action lasting only a quarter of an hour, the American frigate struck her colors to Shannon.

A comment of that blog seems more consistent with Halsted’s version:

Then too, the prevailing wisdom, then and now, is that Lawrence was over-confident and took too much for granted. In an unbroken string of five American victories in ship-to-ship open-ocean duels (three of them frigate battles) Lawrence likely assumed his engagement with Shannon would be no different. Naval historians say Lawrence had no business taking on Shannon–it was not in his orders. he was actually under orders from the Navy Department to break out of Boston harbor and raid British merchant shipping in the Atlantic, not engage in single-ship battles. Additionally, had he had time to learn more about his opponent prior to the action, he might have been a little less rash in running at Broke full-tilt.

Rash or brave? A fine line divides them.