Ker Boyce (1787-1854) was the third great-grandfather of my wife. He was born in upcountry Newberry, South Carolina, (about which more in future blogs) and moved to Charleston. He married first Nancy Johnston; when she died, he married her sister Amanda Caroline Johnston.. My wife’s great grandmother, Elizabeth Miller Boyce, was the child of the second marriage, as was James Pettigru.

In his youth Ker was “mirthful and mischievous,” although he came from Scotch-Irish Presbyterian stock. He became a merchant in Newberry, and in 1813 began to trade overland with Philadelphia because the sea routes were blocked by the British navy during the War of 1812. In 1817 he moved to Charleston and became a commission merchant. He also loaned money to planters. He survived the panic of 1825.

In 1830 Ker and Amanda began attending the sermons of the young Baptist preacher Basil Manly. Manly was called away on church business but hesitated to go because his young son was ill. He and his wife prayed over the decision and he decided to go. On his return he found his child dead. The following Sunday he preached on the text “If I am bereaved of my children, I am bereaved”; and Amanda was converted. This event was to have repercussions in Southern history.

Ker became the wealthiest man in South Carolina. He helped found the Bank of Charleston and became its president. In 1836 he bought a failing sugar company and recapitalized it, and renamed it the Charleston Sugar Refining Company. He was also president of the South Carolina Paper Manufacturing Company. He was on the boards of the South Carolina Railroad, the South Carolina Insurance Company, and the Charleston Gaslight Company. He owned major shares of twenty other companies. He was President of the Charleston Chamber of Commerce. In that role in 1845 Ker offered this sentiment at the occasion of the retirement of the British consul:

“Commerce – The parent of civilization, the nursery of arts, the bond of universal peace.”

Ker owned 9,000 acres near Aiken; he was also an investor in William Gregg’s mill town of Graniteville, which was built on Ker’s land.

Gregg (and presumably Ker) knew that an economy based on the production of raw materials would always be poorer than one (such as in the North) that transformed raw materials into finished products.

Gregg became committed to the idea that South Carolina was wasting its potential by shipping raw cotton to the North and buying back finished goods at exorbitant prices. Keeping local capital within South Carolina would diversify the state’s heavy reliance on cotton growing and provide jobs for the poor whites excluded from the slave-labor economy:

“Let the manufacture of cotton be commenced among us, and we shall soon see the capital that has been sent out of our State returned to us. We shall see the hidden treasures that have been locked up, unproductive and rusting, coming forth to put machinery in motion, and to give profitable employment to the present unproductive labor of our country.”

Dominated by cotton and rice planters, the Charleston elite that Gregg was addressing saw manufacturing as a risky and unsavory enterprise. Gregg argued that manufacturing would not simply make them more like the North but give Southerners independence from their economically dominant Northern neighbors.

Gregg’s opinions about properly creating a community of ready labor for a cotton mill also foreshadow his actions when building the town of Graniteville. In discussing the comparative virtues of slave versus poor white labor, Gregg acknowledged the suitability of slave labor for textile production, but asks “shall we pass unnoticed the thousands of poor, ignorant, degraded white people among us, who, in this land of plenty, live in comparative nakedness and starvation?”

His response to his own question was a classic mix of philanthropy and hard-headed business acumen. Gregg wrote: “It is only necessary to build a manufacturing village of shanties, in a healthy location in any part of the State, to have crowds of these poor people around you, seeking employment at half the compensation given to operatives at the North.”

And if fee labor grew restive, Gregg opined, it could be controlled by the threat of replacement with slave labor. The South could therefore always have a comparative advantage in the price of labor.

Ker was a Unionist Democrat and became a state senator and representative. He wrote to John Calhoun in 1848 to express his dissatisfaction with Northern politicians:

They have no respect for us and thear only object is to see the Negroes Cut our throghts

Ker expresses confidence in Zachary Taylor “as he must be sound on the Main Question [i.e. slavery]. His being a Southern Man and a slave holder give assur[ance]s beyond doubt.

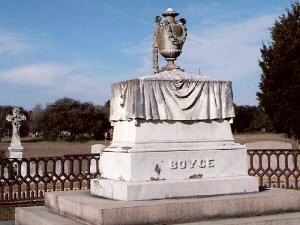

When he died in 1854 he left an estate of about $2,000,000 ($57,000,000 in 2015 dollars).

He left $10,000 for a house for the poor in Graniteville, $20,000 to the Orphan House and $30,000 to the College of Charleston for scholarships for needy students. The rest of the estate was left under the administration of his son James Petigru.

Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston